Usuari:Quimpuig12/proves7

Mangyans[modifica]

Els Mangyans és el nom genèric que es dona als vuit grups indígenes de l'illa de Mindoro, al sud-oest de la illa de Luzon, a les Filipines, tot i que cadascún té el seu nom tribal, la seva llengua i la seva cultura pròpies. La població total seria aproximadament de 280.000, malgrat que és difícil establir un cens oficial a causa de les condicions remotes d'aquestes àrees i de l'aïllament dels grups tribals amb poc o nul contacte amb la resta del món.

Els grups ètnics de l'illa són, de nord a sud: Irayes, Alangans, Tadyawans, Tawbuids (anomenats Batangan pels habitants de les terres baixes de l'oest de l'illa), Buhids, i Hanunoos. Un grup addicional de la costa del sud és anomenat Ratagnon. Sembla que són habituals els matrimonis interètnics amb els habitants de les terres baixes. El grup de l'est de Mindoro conegut com Bangon pot ser un subgrup de Tawbuid, ja que parlen el dialecte 'occidental' d'aquella llengua. També tenen una mena de literatura anomenada Ambahan.

Orígens[modifica]

Els Mangyans eren antigament els únics habitants de Mindoro. Al principi habitaven la zona costanera, però van emigrar cap a l'interior i les muntanyes per evitar la presència i la influència dels colons forasters, tant els tagàlogs com els espanyols, els seus saquejos i conversions religioses, i les batudes dels Moros (que assaltaven poblaments espanyols per propòsits religiosos, i per satisfer la demanda per treball esclau). Avui, els Mangyans viuen aïllats en zones remotes de Mindoro però ocasionalment baixen a la plana costanera per tal de fer comerç. El seu mitjà de subsistència és la recol·lecció dels seus propis cultius i fruites i la caça. Hi ha un grup de Mangyans del sud de Mindoro que s'anomenen a ells mateixos Hanunuo Mangyans, és a dir, "els veritables", "purs" o "genuïns", un terme que utilitzen per accentuar el fet que són estrictes en la preservació les tradicions i pràctiques ancestrals.[1][2]

Abans de l'arribada dels espanyols a Mindoro hi havia hagut una gran relació comercial amb la Xina, com demostren milers d'evidències arqueològiques trobades a Puerto Galera i en referències escrites xineses. Amb la colonització espanyola la població es va dividir entre els Iraya Mangyans, que es van aïllar de la cultura dels espanyols, i els cristians de les terres baixes, que es van sotmetre a la nova dominació i a les seves creences. Aquests dos grups només interaccionaven pel comerç intercanviant productes del bosc dels mangyans i béns de consum dels habitants de les terres baixes.[3][4]

Malgrat que han estat classificats com una sola tribu, els mangyans presenten nombroses diferències entre ells. Pel que fa a l'avenç tecnològic, atenen a les dues subdivisions geogràfiques, les tribus del sud són més avançades en la tècnica del teixit, la ceràmica i el sistema d'escriptura. Les tribus del nord, d'altra banda, tenen unes formes de vida més senzilles. La llengua, com la resta de les llengües de les Filipines, pertanyen a la família austronèsia. Tanmateix, encara que es defineixin com un sol grup ètnic, les tribus parlen llengües diferents. De mitjana, només comparteixen un 40% del seu vocabulari. Les tribus també tenen diferències en l'aspecte físic i etnogenètiques: Els iraya tenen característiques austroloides; els tadyawan són principalment mongoloides; i els hanunuo semblen proto-malais.

na altra diferència entre tribus és la data de la seva arribada a les Filipines. Una teoria suggereix que les tribus del sud eren ja habitaven l'illa al 900 DC mentre que es creu que les tribus del nord van arribar centenars d'anys més tard. Les autoritats espanyoles havien documentat la seva existència des de la seva arribada al segle XVI. Tanmateix, els historiadors suggereixen que el Mangyans podrien haver estat els primers filipins que van comerciar amb els xinesos. Les evidències d'aquesta relació s'han trobat en les coves funeràries, tals com peces de porcellana i abundants peces de ceràmica. Tanmateix, no s'ha fet gaire recerca etnogràfica excepte les diferències tribals i lingüístiques que poden dirigir a la indicació que les tribus poden ser classificades per separat.

Cultura i pràctiques[modifica]

Els mangyans vivien en societats pacífiques en comparació amb les tribus de caçadors de caps del nord de Luzon i les bel·licoses tribus guerreres del sud. Des de l'antropologia s'ha llançat la teoria que algunes societats esdevenen pacífiques perquè el seu sistema de normes i valors premia el comportament pacífic però desaprova els comportaments agressius i impulsius. Les societats pacífiques es caracteritzen per una organització social igualitària sense competència d'estatus entre homes i amb una relació no asimètrica entre homes i dones. Una altra teoria postula que les poblacions s'adapten, això oferiria una explicació més lògica del fet que els Mangyans van preferir retrocedir cap a l'interior. Accepten pacíficament la submissió quan s'acaren amb els colons de les terres baixes, missioners, comerciants i funcionaris.[5]

Els mangyan es dediquen principalment a l' agricultura de subsistència, i planten una varietat de patata dolça, arròs de muntanya (cultiu sec), i taro. També cacen animals petits i porcs salvatges. Molts dels que tenen contacte proper amb els filipins de les terres baixes mercadegen les seves collites tals com plàtans i gingebre.

Les seves llengües són mútuament inintel·ligibles, encara que comparteixen part del lèxic i l'ús de l'escriptura Hanunó'o, molt propera al Tawbuid i Buhid, i es diferencia d'altres llengües filipines pel fet de tenir el fonema /f/; el tawbuid es divideix en dialectes orientals i occidentals; el tawbuid occidental és segurament l'única llengua filipina que no té cap consonant glotal, no disposa de /h/ ni /ʔ/.

La seva visió religiosa tradicional del món és principalment animistica; al voltant d'un 10% ha abraçat el cristianisme, tant el catolicisme com el protestantisme evangèlic (El Nou Testament ha estat publicat en sis de les llengües Mangyan).

Religió Mangyan indígena[modifica]

Els Mangyan tenen un sistema de creences espirituals complexes que inclouen les deïtats següents:

- Mahal na Makaako – El Ser Suprem que va donar vida a tots els éssers humans merament per mirar fixament a ells.

- Binayi – L'amo d'un jardí on resten els esperits.

- Binayo – És un esperit sagrat femení que té cura dels esperits de l'arròs o kalag paray. És casada amb Bulungabon. Els kalag paray s'han de satisfer per assegurar una collita abundosa. Per això hi ha uns rituals específics per a cada fase del cultiu de l'arròs. Alguns d'aquests rituals són el panudlak, el ritu de la sembra; el ritu de la plantada; i els ritus de la collita que consisteixen en el magbugkos o nuats de tiges d'arròs, i el pamag-uhan, posterior a la collita.

- Bulungabon – Esperit assistit per 12 gossos feroços. Les ànimes pecadores són empaitades per aquests gossos i finalment ofegades en una caldera d'aigua bullent. És el marit de Binayo .

Artesania[modifica]

El indígenes mangyans confeccionen una gran varietat d'utensilis de rica artesania que, mostra de la seva cultura i comerç. Els habitants del sud de Mindoro a l'era pre-hispànica destacaven en l'art de teixir, la ceràmica i sistema d'escriptura. La roba és diferent segons el gènere. Els homes porten generalment un tapall mentre mentre que les dones porten una faldilla i una camisa. Els teiixits són tenyits en blau indi i tenen un disseny brodat anomenat pakudos a la part del darrera i també a les bosses de roba.

El seu sistema d'escriptura pre-hispànic anomenat buhid, burat mangyan o mangyan baybayin, és un abugida de la família bràmica. Actualment encara s'utilitza i s'ensenya en escoles mangyan de Mindoro oriental. Els Hanunó'os també conreen la seva poesia tradicional anomenada Ambahan, una expressió poètica rítmica amb un metre de set síl·labes que s'expressa recitada o cantada i escrita sobre bambú.[6][7][8]

Referències[modifica]

Enllaços externs[modifica]

- Mangyan Centre de patrimoni

- La llegenda del Blanc Mangyans – Olandes

- iWitness: Ang Alamat ng Puting Mangyan – 29 gener 2008 (en Filipino)

Article per traduir. Bloc de Cascajal[modifica]

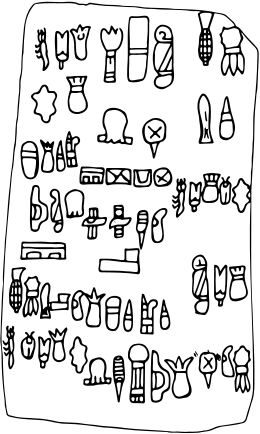

El Bloc de Cascajal és un petit bloc de pedra de serpentinita de la mida d'una tauleta, que conté 62 glifs, d'uns 3000 anys d'antiguitat, aproximadament, gravat amb caràcters de significat desconegut fins al dia d'avui, que es creu que podria ser una mostra del sistema d'escriptura més antic del continent americà, pertanyent a la civilització olmeca.[9]

The Cascajal Block was discovered by road builders in the late 1990s in a pile of debris in the village of Lomas de Tacamichapan in the Veracruz lowlands in the ancient Olmec heartland of coastal southeastern Mexico. The block was found amidst ceramic shards and clay figurines and from these the block is dated to the Olmec archaeological culture's San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán phase, which ended c. 900 BCE, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing dated to about 500 BCE

El bloc de Cascajal va ser descobert per uns constructors de carreteres a finals de 1990 en un munt de runes a la localitat de Lomas de Tacamichapan a Veracruz a l'antiga àrea nuclear olmeca de la costa sud-est de Mèxic. El bloc es troba enmig de fragments de ceràmica i figuretes de fang i d'aquests el bloc es data als Olmecas cultura arqueològica 's Sant Llorenç Tenochtitlán fase, que va acabar c. 900 aC, que precedeix a la més antiga [cultura zapoteca [| zapoteca]] escrit datat al voltant de 500 aC.[10][11] Archaeologists Carmen Rodriguez and Ponciano Ortiz of the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico examined and registered it with government historical authorities. It weighs about 11.5 kg (25 lb) and measures 36 cm × 21 cm × 13 cm. Details of the find were published by researchers in the 15 September 2006 issue of the journal Science.[12]

Putative Olmec writing system[modifica]

The Olmec flourished in the Gulf Coast region of Mexico, ca. 1250–400 BCE. The evidence for this writing system is based solely on the text on the Cascajal Block.

The block holds a total of 62 glyphs, some of which resemble plants such as maize and pineapple, or animals such as insects and fish. Many of the symbols are more abstract boxes or blobs. The symbols on the Cascajal block are unlike those of any other writing system in Mesoamerica, such as in Mayan languages or Isthmian, another extinct Mesoamerican script. The Cascajal block is also unusual because the symbols apparently run in horizontal rows and "there is no strong evidence of overall organization. The sequences appear to be conceived as independent units of information".[13] All other known Mesoamerican scripts typically use vertical rows.

La cultura olmeca va florir a la regió de la costa del Golf de Mèxic, ca. 1250-400 aC. L'evidència d'aquest sistema d'escriptura es basa únicament en el text en el bloc de Cascajal.

El bloc té un total de 62 glifs, alguns dels quals semblen plantes com el blat de moro i la pinya, o animals com ara insectes i peixos. Molts dels símbols són quadres més abstractes o taques. Els símbols del bloc de Cascajal són diferents de les de qualsevol altre sistema d'escriptura de Mesoamèrica, com per exemple en les llengües maies o ístmica, una altra escriptura mesoamericana extingit. El bloc de Cascajal és també inusual perquè els símbols estan disposats en files horitzontals i no hi ha una "evidència clara d'organització en general. Les seqüències semblen estar concebuts com a unitats independents d'informació". [5] Totes les altres seqüències d'ordres mesoamericanos coneguts solen utilitzar files verticals.

Assessment by archaeologists and other specialists[modifica]

Authors of the report[modifica]

- Stephen D. Houston, who also worked on the study, said the text, if decoded, will decipher "earliest voices of Mesoamerican civilization."[9] "Some of the pictographic signs were frequently repeated, particularly ones that looked like an insect or a lizard." Houston suspected that "these might be signs alerting the reader to the use of words that sound alike but have different meanings—as in the difference between 'I' and 'eye' in English." He concluded, "the linear sequencing, the regularity of signs, the clear patterns of ordering, they tell me this is writing. But we don't know what it says."[14]

- "This is extremely important because we never recognized this writing system, until this discovery," said archaeologist Karl Taube of the University of California, Riverside, who was involved in the documentation and publication of the discovery. "We've known they have very elaborate art, and iconography, but this is the first strong indication that they had visually recorded speech."[15]

- For Richard Diehl of the University of Alabama, the discovery announced in the journal Science amounted to rock-solid proof that the Olmecs had a form of writing. Diehl has believed "all along" that the Olmecs possessed the ability to write and discovery of the stone "corroborates my gut feelings."[16]

Additional support[modifica]

- William Saturno, not involved in the study, agreed with Houston that the horizontally arranged inscription shows patterns that are the hallmarks of true writing, including syntax and language-specific word order. "That's full-blown, legitimate text—written symbols taking the place of spoken words,"[17] said Saturno, a University of New Hampshire anthropologist and expert in Mesoamerican writing.

- Mary Pohl at Florida State University is an expert on the Olmec. She said "One sign looks actually like a corn cob with silk coming out the top. Other signs are unique, and never before seen, like one of an insect... These objects—and thus probably the writing—had a special value in rituals…We see that the writing is very closely connected with ritual and the early religious beliefs, because they are taking the ritual carvings and putting them into glyphs and making writing out of them. And all of this is occurring in the context of the emergence of early kings and the development of a centralized power and stratified society."[18]

- David Stuart, a University of Texas at Austin expert in Mesoamerican writing, was not connected with the discovery, but reviewed the study for Science. He said "To me, this find really does bring us back to this idea that at least writing and a lot of the things we associate with Mesoamerican culture really did have their origin in this region."[19]

- Lisa LeCount, an associate professor of archaeology at the University of Alabama, theorized that, if it is a crown, it might have been carved into the stone to establish leadership. "The stone could have been used as a tool by an emerging king to validate his exalted position and to legitimize his right to the throne. Only the elite in that society would have known how to read and write."[16] LeCount said there should be no question that the Olmecs represented the "mother culture" and predated the Mayans, whose writings and buildings remain to this day.

- Caterina Magni, an Associate Professor of Prehispanic Archaeology at the Paris-Sorbonne University, presents a new interpretation of the Cascajal Block. Initially, the author interpreted each glyph in an isolated way. In the second time, C. Magni proposes a religious and ritual reading of the text. It's an initiation rite which takes place an underground location that include self-sacrificiel practices. "This elaborate code supports and expresses an extremely sophisticated manner of thinking, which refers primarily to religious notions but also, to a lesser extent, to the socio-political domain."[20] In 2014 Caterina Magni argued, in the book Les Olmèques. La genèse de l’écriture en Méso-Amérique. that the Cascajal block is carved with glyohs which belong to the Olmec vocabulary and demonstrates that this ancient people invented the writing. Magni proposes a new approach to the graphic code of the Olmecs and offers a new perspective on their system of thought, as well as proposing a dictionary of Olmec glyphs and symbols.[21]

- David Freidel and F. Kent Reilly III proposed, in 2010, that, rather than a unique script, the Cascajal Block in fact represents a special arrangement of sacred objects used in ancient times for magical purposes.[22] They propose that the incised symbols on the block represent the contents of three sacred bundles arranged in three separate registers from top to bottom. These sacred bundles include well known objects used in magic and divination rituals. Many of these objects/signs, arranged horizontally within the registers, are present in all three registers. The whole block is to be read in boustrophedon fashion from top to bottom and alternatively left to right and right to left. Freidel and Reilly argue that the majority of the symbols on the block are found in the established corpus of Middle Formative art and many are otherwise part of iconographically comprehensible compositions that are designed to be read pictographically and not as script encoding spoken language. Rather than to regard the Cascajal Block as an epistemological dead-end—the conclusion if it is identified as a unique script—they identify the block as a key to understanding a special arrangement of sacred objects presented in the course of a religious ritual. The purpose of this may have been to memorialize the acts of divination or other magical rituals. This was a pervasive ritual practice well attested in the archaeology of Formative period Mesoamerica.[22]

Skepticism[modifica]

Some archaeologists are skeptical of the tablet:

- For David Grove, an archaeologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville who was not involved in the research, the tablet "looked like a fake to me because the symbols are laid out in horizontal rows,"[23] unlike the region's other writing systems, he said.

- Archaeologist Christopher Pool of the University of Kentucky in Lexington said in 2010 "I've always been a little skeptical of it. "For one, it's unique," he continued. Another critical issue, Pool adds, is that when Rodriguez and Ortiz retrieved the tablet, it was already removed from the ground, taking it out of its original archaeological context."[23]

- Max Schvoerer, professor at Michel de Montaigne University, and founder of the Laboratoire de Physique appliquée à l'Archéologie, said "Unfortunately, the authors determined the age of the block only indirectly, by studying ceramics shards found at the site, in the absence of a well identified and dated level of occupation."[24]

Formal criticism[modifica]

The most comprehensive criticism was published in the journal Science, the publisher of the original study, on 9 March 2007. In a letter, archaeologists Karen Bruhns and Nancy Kelker raise five points of concern:[25]

- The block was found in a pile of bulldozer debris and cannot be reliably dated.

- The block is unique. There is no other known example of Olmec drawing, much less writing, on a serpentine slab.

- All other Mesoamerican writing systems are written either vertically or linearly. The glyphs on the block are arranged in neither format but instead "randomly bunch".

- As pointed out by the original authors, some of the glyphs do appear on other Olmec artifacts, but have never been heretofore identified as writing, only as decorative motifs.

- "What we can only describe as the 'cootie' glyph (#1/23/50) fits no known category of Mesoamerican glyph and, together with the context of the discovery, strongly suggests a practical joke".

A rebuttal to the criticism by the authors of the original study was published directly following the letter:

- Other critical Mesoamerican finds, as well as the Rosetta Stone, were also found without provenance.

- Such inscriptions are faint and may as yet be unseen on previously discovered slabs.

- The signs are in a "purposeful" pattern.

- "All known hieroglyphic systems in the world relate to pre-existing iconography or codified symbolism", and therefore it is not surprising that the Cascajal glyphs appear in other contexts as motifs.

- The 'cootie' glyph can be found in "three-dimensional" form on San Lorenzo Monument 43.

See also[modifica]

- San Andrés - an Olmec site where artifacts related to another proposed Olmec writing system have been found

- Olmec

- Maya script

- Maya writing system

- Mesoamerican chronology

- San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán

- Isthmian script

Notes[modifica]

- ↑ «Mangyan Tribes in Mindoro». Precious Heritage Ministries. [Consulta: 29 December 2014].

- ↑ Non, Domingo Southeast Asian Studies, 30, 4, 1993, pàg. 401-419 [Consulta: 29 December 2014].

- ↑ Bawagan, A. B. (2009). Customary Justice System among the Iraya Mangyans of Mindoro. AGHAMTAO: Journal of Ugnayang Pang-Aghamtao, Inc. (UGAT), Volume 17, 16.

- ↑ Lopez, V. B. (1976). The Mangyans of Mindoro: An ethnohistory (1st ed.). Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- ↑ Santos, Jericho Paul. «The Culture and Art of the Mangyan». Artes de las Islas Filipinas. [Consulta: 29 December 2014].

- ↑ Santos, Jericho Paul. «The Culture and Art of the Mangyan». Artes de las Islas Filipinas. [Consulta: 29 December 2014].

- ↑ «Mangyan Syllabic Script». Mangyan Heritage Center.

- ↑ «Ambahan». Mangyan Heritage Center. [Consulta: 29 December 2014].

- ↑ 9,0 9,1 «Earliest writing in New World discovered» (en anglès). In the News, 15-09-2006 [Consulta: 11 febrer 2017].

- ↑ «'Oldest' New World writing found». BBC, 14-09-2006 [Consulta: 30 març 2008]. «Ancient civilisations in Mexico developed a writing system as early as 900 BC, new evidence suggests.»

- ↑ «Oldest Writing in the New World». [Consulta: 30 març 2008]. «A block with a hitherto unknown system of writing has been found in the Olmec heartland of Veracruz, Mexico. Stylistic and other dating of the block places it in the early first millennium before the common era, the oldest writing in the New World, with features that firmly assign this pivotal development to the Olmec civilization of Mesoamerica.»

- ↑ In a paper entitled "Oldest Writing in the New World", see Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2006)

- ↑ Quote taken from Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2006).

- ↑ Researchers find ancient script on stone, in Bay Area News, 15 September 2006

- ↑ Oldest New World Writing Discovered Arxivat October 23, 2006, a Wayback Machine., in All Headline News, 16 September 2006

- ↑ 16,0 16,1 Tablet has example of early writing Arxivat October 28, 2006, a Wayback Machine., in Montgomery Advertiser, 17 September 2006

- ↑ Stone slab bears earliest writing in the Americas, in Mohave Daily News , 16 September 2006

- ↑ Earliest New World Writing Discovered, in National Public Radio, Morning Edition, 15 September 2006

- ↑ A Stone Age Scoop, in CBS News, 15 September 2006

- ↑ Magni (2008), pp.64–81

- ↑ Caterina Magni (2014), Les Olmèques. La genèse de l’écriture en Méso-Amérique edited by Errance/Actes Sud, Paris/Arles. pp. 130–142. ISBN 9782877725439

- ↑ 22,0 22,1 David Freidel and F. Kent Reilly III (2010), The Flesh of God: Cosmology, Food, and the Origins of Political Power in Ancient Southeastern Mesoamerica. in Pre-Columbian Foodways: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Food, Culture, and Markets in Mesoamerica edited by John E. Staller and Michael D. Carrasco. pp. 635–680. Springer. ISBN 1441904719

- ↑ 23,0 23,1 Oldest Writing in New World Discovered, Scientists Say, in National Geographic News, 14 September 2006

- ↑ Débat autour de la découverte d'une stèle olmèque, in Le Monde, 17 September 2006

- ↑ Bruhns, et al.

References[modifica]

- Bruhns, Karen O. «Did the Olmec Know How to Write?». Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science [Washington, DC], vol. 315, 5817, 09-03-2007, pàg. 1365–1366. DOI: 10.1126/science.315.5817.1365b. OCLC: 206052590. PMID: 17347426.

- Houston, Stephen D.. «Writing in Early Mesoamerica». A: Stephen D. Houston (ed.). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 274–309. ISBN 0-521-83861-4. OCLC 56442696.

- Rodríguez Martínez, Ma. del Carmen «Oldest Writing in the New World». Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science [Washington, DC], vol. 313, 5793, 16-09-2006, pàg. 1610–1614. DOI: 10.1126/science.1131492. OCLC: 200349481. PMID: 16973873.

- Skidmore, Joel. «The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing» (PDF). Mesoweb Reports & News. Mesoweb, 2006. [Consulta: 20 juny 2007].

- Magni, Caterina. «Olmec Writing The Cascajal "Block" - New Perspectives» (PDF). Arts & Cultures 2008: Antiquité, Afrique, Océanie, Asie, Amérique p. 64–81. Paris, Genève/Barcelona: Somogy Éditions d'art, in collaboration with The Association of Friends of the Barbier-Mueller Museum, 2008. [Consulta: 8 febrer 2012].

- Magni, Caterina. Les Olmèques. La genèse de l’écriture en Méso-Amérique. Paris, Arles, éditions: Errance, 2014, p. 130–142. ISBN 978-2877725439.

External links[modifica]

De la Llista de monuments de Casserres[modifica]

- Ajuntament (Castell de Casserres (Berguedà))

- Carrer Major

- Cal Biel (Casserres)

- Església de Santa Maria de l'antiguitat

- Cal Barnadàs

- Ca n'Eloi (Casserres)

- Església de Sant Miquel de Fonogedell

- Cal Cirera (Casserres)

- Soler de Sant Pau

- Bernades

- Altres masies que no surten als monuments de Casserres, vegeu: Llista de masies de Casserres

Si es vol ampliar el camp d'acció[modifica]

La Llista de monuments d'Avià i la Llista de monuments de Viver i Serrateix tenen gairebé tots els elements sense foto.