Usuari:Bestiasonica/Poliadenilació

| Aquest article tenia importants deficiències de traducció i ha estat traslladat a l'espai d'usuari. Podeu millorar-lo i traslladar-lo altra vegada a l'espai principal quan s'hagin resolt aquestes mancances. Col·laboreu-hi! |

|

|

Aquest article o secció necessita millorar una traducció deficient. |

|

|

Aquest article o secció s'està traduint a partir de: «Polyadenylation» (anglès) en la versió del 6 December 2013, amb llicència CC-BY-SA Hi pot haver llacunes de contingut, errors sintàctics o escrits sense traduir. |

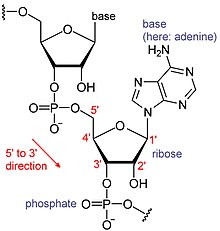

La poliadenilació és l'addició d'una cua de poli(A) a un transcrit primari d'ARN. La cua de poli(A) consta de múltiples monofosfats d'adenosina, en altres paraules, es tracta d'un fragment d'ARN que inclou únicament bases d'adenina. En eucariotes, la poliadenilació és part del procés de maduració de l'ARN missatger (ARNm) per a la traducció. És, per tant, part d'un procés més ampli de l'expressió gènica.

The process of polyadenylation begins as the transcription of a gene finishes, or terminates. The segment of the newly made pre-mRNA is first cleaved off by a set of proteins; these proteins then synthesize the poly(A) tail at the RNA's 3' end. In some genes, these proteins may add a poly(A) tail at any one of several possible sites. Therefore, polyadenylation can produce more than one transcript from a single gene (alternative polyadenylation), similar to alternative splicing

El procés de poliadenilació comença tan bon punt acaba la transcripció d'un gen. El segment del pre-mRNA acabat de sintetitzar s'escindeix primer de tot per l'acció d'un complex proteic, aquestes proteïnes després sintetitzen la cua poli(A) a l'extrem 3' de l'ARN. En alguns gens, aquestes proteïnes poden afegir una cua de poli(A) a qualsevol de diversos llocs possibles. Per tant, de poliadenilació pot produir més d'una transcripció a partir d'un sol gen (de poliadenilació alternativa), similar a tall i empalmament alternatiu.[1]

La cua de poli(A) juga un paper clau per a l'exportació nuclear, la traducció, i l'estabilitat de l'ARNm. La cua s'escurça amb el temps, i, quan és prou curta, l'ARNm es degrada enzimàticament.[2] No obstant això, en alguns tipus de cèl·lules, els ARNm amb cues curtes de poli(A) s'emmagatzemen per a una posterior activació mitjançant una posterior poliadenilació en el citosol.[3] En contrast, quan es produeix la poliadenilació en bacteris aquesta promou la degradació de l'ARN.[4] Aquest també és de vegades el cas dels ARN no codificants eucariotes.[5]

The poly(A) tail is important for the nuclear export, translation, and stability of mRNA. The tail is shortened over time, and, when it is short enough, the mRNA is enzymatically degradedHowever, in a few cell types, mRNAs with short poly(A) tails are stored for later activation by re-polyadenylation in the cytosol. In contrast, when polyadenylation occurs in bacteria, it promotes RNA degradation. This is also sometimes the case for eukaryotic non-coding RNAs

Paper de l'ARN[modifica]

L'ARN és un tipus de molècula biològica grans, els blocs de construcció individuals són anomenats nucleòtids. El nom de cua de poli(A) - cua d'àcid poliadenílic -[6] reflecteix la forma en què els nucleòtids de l'ARN es processen, amb una lletra per a la base del nucleòtid que conté (A per adenina, C per citosina, G per la guanina i U per l'uracil). L'ARN es produeix (transcrit) a partir d'un motlle d'ADN. Per convenció, les seqüències d'ARN s'escriuen en una direcció 5' a 3'. L'extrem 5' és la part de l'ARN que primer es transcriu, i l'extrem 3' es transcriu últim. L'extrem 3' és també on hi ha la cua de poli(A) en l'ARN poliadenilat.[1][7]

L'ARN missatger (ARNm) és ARN que té una regió codificant que actua com a motllo per a la síntesi de proteïnes (traducció). La resta de l'ARNm, les regions no traduïdes, modulen el mode i la intensitat en que l'ARNm es tradueix.[8] També hi ha molts ARN que no es tradueixen, anomenats ARNs no codificants. Igual que les regions no traduïdes, molts d'aquests ARN no codificants tenen funcions reguladores.[9]

Poliadenilació nuclear[modifica]

Funció[modifica]

En la poliadenilació nuclear, s'afegeix un polímer de cua de poli(A) a un ARN a l'extrem de la transcripció. En els ARNm, la cua de poli(A) protegeix la molècula d'ARNm de la degradació enzimàtica en el citoplasma i ajuda en la terminació de la transcripció, l'exportació de l'ARNm des del nucli cap al citosol, i la traducció.[2] Gairebé tots els ARNm eucariòtics estan poliadenilats,[10] amb a excepció dels ARNm animals d'histones replicació dependent.[11] Aquests són els únics ARNm en eucariotes que no tenen una cua de poli(A), acabant en lloc d'una estructura tija - bucle seguit per una seqüència rica en purines, que dirigeix on es talla l'ARN de manera que es forma l'extrem 3' de l'ARNm de la histona.[12]

Molts ARN no codificants eucariotes sempre es poliadenilen al final de la transcripció. Hi ha petits RNAs on la cua de poli(A) es veu només en les formes intermèdies i no en l'ARN madur com s'eliminen els extrems durant el processament, els més notables sent microRNAs.[13][14] No obstant això, per a molts ARNs no codificants llargs - un aparentment grup gran d'ARNs de regulació que, per exemple, inclou l'ARN de Xist, que hi la inactivació del cromosoma X - un la cua de poli(A) forma part de l'ARN madur.[15]

In nuclear polyadenylation, a poly(A) tail is added to an RNA at the end of transcription. On mRNAs, the poly(A) tail protects the mRNA molecule from enzymatic degradation in the cytoplasm and aids in transcription termination, export of the mRNA from the nucleus, and translationAlmost all eukaryotic mRNAs are polyadenylatedwith the exception of animal replication-dependent histone mRNAsThese are the only mRNAs in eukaryotes that lack a poly(A) tail, ending instead in a stem-loop structure followed by a purine-rich sequence, termed histone downstream element, that directs where the RNA is cut so that the 3' end of the histone mRNA is formed

Many eukaryotic non-coding RNAs are always polyadenylated at the end of transcription. There are small RNAs where the poly(A) tail is seen only in intermediary forms and not in the mature RNA as the ends are removed during processing, the notable ones being microRNAsBut, for many long noncoding RNAs – a seemingly large group of regulatory RNAs that, for example, includes the RNA Xist, which mediates X chromosome inactivation – a poly(A) tail is part of the mature RNA

Mechanism[modifica]

| Proteins involved:[10] CPSF: cleavage/polyadenylation specificity factor |

La maquinària de poliadenilació en el nucli dels eucariotes treballa en productes d'ARN polimerasa II, com ara pre-mRNA. Aquí, un complex multi - proteïna (vegeu components a la dreta) s'escindeix el 3' - major part d'un ARN acabat de produir i polyadenylates final produït per aquesta escissió. L'escissió està catalitzada per l'enzim CPSF[11] i es produeix 10-30 nucleòtids riu avall del seu lloc d'unió.[16] Aquest lloc és sovint el AAUAAA seqüència en l'ARN, però existeixen variants de la mateixa que s'uneixen més dèbilment a CPSF.[17] Dues proteïnes afegeixen especificitat a la unió a un ARN: CstF i TPI. CSTF s'uneix a un GU- rica regió aigües avall del lloc de CPSF. .[18] TPI reconeix una tercera lloc en l'ARN (un conjunt de seqüències UGUAA en els mamífers[19][20][21]) i pot reclutar CPSF encara que el seqüència AAUAAA de falta[22][23] el senyal de poliadenilació -. el motiu de seqüència reconegut pel complex d'escissió d'ARN - varia entre els grups d'eucariotes. La majoria dels llocs de poliadenilació humans contenen la seqüència AAUAAA,[18] però aquesta seqüència és menys comú en les plantes i els fongs.[24]

The polyadenylation machinery in the nucleus of eukaryotes works on products of RNA polymerase II, such as precursor mRNA. Here, a multi-protein complex (see components on the right) cleaves the 3'-most part of a newly produced RNA and polyadenylates the end produced by this cleavage. The cleavage is catalysed by the enzyme and occurs 10–30 nucleotides downstream of its binding siteThis site is often the sequence AAUAAA on the RNA, but variants of it that bind more weakly to CPSF existTwo other proteins add specificity to the binding to an RNA: CstF and CFI. CstF binds to a GU-rich region further downstream of CPSF's siteCFI recognises a third site on the RNA (a set of UGUAA sequences in mammalsand can recruit CPSF even if the AAUAAA sequence is missing.The polyadenylation signal – the sequence motif recognised by the RNA cleavage complex – varies between groups of eukaryotes. Most human polyadenylation sites contain the AAUAAA sequencebut this sequence is less common in plants and fungi

The RNA is typically cleaved before transcription termination, as also binds to RNA polymerase IIThrough a poorly understood mechanism (as of 2002), it signals for RNA polymerase II to slip off of the transcriptCleavage also involves the protein CFII, though it is unknown howThe cleavage site associated with a polyadenylation signal can vary up to some 50 nucleotides

L'ARN s'escindeix típicament abans d'acabar la transcripció, com CstF també s'uneix a l'ARN polimerasa II.[25] a través d'un mecanisme pobrament comprès, que assenyala a l'ARN polimerasa II aturar la transcripció.[26] L'escissió també implica proteïnes CFII, encara que es desconeix com passa.[27] El lloc de tall associat amb un senyal de poliadenilació pot variar fins a uns 50 nucleòtids.[28]

Quan s'escindeix l'ARN, s'inicia la poliadenilació, catalitzada per la poliadenilat polimerasa. La poliadenilat polimerasa construeix la cua de poli(A) mitjançant l'addició d'unitats d'adenosina monofosfat d'adenosina trifosfat a l'ARN, escindint pirofosfat.[29] Una altra proteïna, PAB2, s'uneix a la nova, poli curt (A) de cua i augmenta l'afinitat de la polimerasa de poliadenilat per l'ARN. Quan la cua de poli(A) té una llargada d'uns 250 nucleòtids l'enzim ja no pot unir-se a CPSF i la poliadenilació s'acaba, determinant així la longitud de la cua de poli(A).[30][31] CPSF està en contacte amb l'ARN polimerasa II, que assenyala a la polimerasa d'acabar la transcripció.[32][33] Quan l'ARN polimerasa II arriba a una "seqüència de terminació" (TTATT al motllo d'ADN i AAUAAA en la transcripció primària), assenyala la fi de la transcripció.[34] la maquinària de poliadenilació també està vinculada físicament a l'espliceosoma, un complex que elimina els introns de l'ARN.[23]

When the RNA is cleaved, polyadenylation starts, catalysed by polyadenylate polymerase. Polyadenylate polymerase builds the poly(A) tail by adding adenosine monophosphate units from adenosine triphosphate to the RNA, cleaving off pyrophosphateAnother protein, PAB2, binds to the new, short poly(A) tail and increases the affinity of polyadenylate polymerase for the RNA. When the poly(A) tail is approximately 250 nucleotides long the enzyme can no longer bind to CPSF and polyadenylation stops, thus determining the length of the poly(A) tailCPSF is in contact with RNA polymerase II, allowing it to signal the polymerase to terminate transcriptionWhen RNA polymerase II reaches a "termination sequence" (TTATT on the DNA template and AAUAAA on the primary transcript), the end of transcription is signaledThe polyadenylation machinery is also physically linked to the spliceosome, a complex that removes introns from RNAs

Downstream effects[modifica]

La cua de poli(A) actua com el lloc d'unió per la proteïna d'unió a poli(A). proteïna d'unió a poli(A) promou l'exportació des del nucli i la traducció, i inhibeix la degradació.[35] Aquesta proteïna s'uneix a la cua de poli(A) abans de l'exportació de l'ARNm des del nucli i en llevats també s'uneiox a la nucleasa de poli(A), un enzim que escurça la cua poli(A) i permet l'exportació d'ARNm. Proteïna Poli (A)-vinculant s'exporta al citoplasma amb l'ARN. ARNm que no s'exporten són degradats per l'exosoma.[36][37] poli(A) la proteïna d'unió també pot unir-se a, i per tant contractar, diverses proteïnes que afecten la traducció,[36] Un d'ells és el factor d'iniciació 4G, que al seu torn recluta la subunitat ribosòmica 40S.[38] No obstant això, un poli(A) cua no es requereix per a la traducció dels mRNAs.[39]

The poly(A) tail acts as the binding site for poly(A)-binding protein. Poly(A)-binding protein promotes export from the nucleus and translation, and inhibits degradationThis protein binds to the poly(A) tail prior to mRNA export from the nucleus and in yeast also recruits poly(A) nuclease, an enzyme that shortens the poly(A) tail and allows the export of the mRNA. Poly(A)-binding protein is exported to the cytoplasm with the RNA. mRNAs that are not exported are degraded by the exosome Poly(A)-binding protein also can bind to, and thus recruit, several proteins that affect translationone of these is initiation factor-4G, which in turn recruits the ribosomal subunitHowever, a poly(A) tail is not required for the translation of all mRNAs

Desadenilació[modifica]

En les cèl·lules somàtiques eucariotes, la cua de poli(A) de la majoria dels ARNm en el citoplasma arribar gradualment més curt i més curt amb els ARNm poli(A) cua es tradueixen menys i degrada abans.[40] Tanmateix, pot prendre moltes hores abans d'un ARNm es degrada.[41] Aquest procés deadenylation i la degradació pot ser accelerada per microARN complementaris a la regió no traduïda 3' d'un ARNm.[42] En les cèl·lules immadures d'ou, els ARNm amb cues poli escurçat (a) no es degrada, sinó que està emmagatzemat sense ser traduït. A continuació, s'activen per poliadenilació citoplasmàtica després de la fecundació, durant l'activació de l'oocit.[43]

En els animals, poli(A) de ribonucleasa (Pärn) es pot unir al caputxó 5' i eliminar els nucleòtids de la cua de poli(A). El nivell d'accés als 5 'cap i poli(A) cua és important per a controlar amb quina rapidesa es degrada l'ARNm. Pärn deadenylates menys si l'ARN està obligat per la iniciació factors 4E (a la caputxó 5') i 4G (a la cua de poli(A)), de manera que la traducció es redueix deadenylation. La taxa de deadenylation també pot ser regulada per les proteïnes d'unió d'ARN -. Una vegada que s'elimina la cua poli(A), el complex decapping treu la caputxó 5', que condueix a una degradació de l'ARN. Diverses altres enzims que semblen estar involucrats en deadenylation s'han identificat en el llevat.[44]

In eukaryotic somatic cells, the poly(A) tail of most mRNAs in the cytoplasm gradually get shorter, and mRNAs with shorter poly(A) tail are translated less and degraded soonerHowever, it can take many hours before an mRNA is degradedThis deadenylation and degradation process can be accelerated by microRNAs complementary to the 3' untranslated region of an mRNAIn immature egg cells, mRNAs with shortened poly(A) tails are not degraded, but are instead stored without being translated. They are then activated by cytoplasmic polyadenylation after fertilisation, during [[egg activation

In animals, poly(A) ribonuclease (PARN) can bind to the 5' cap and remove nucleotides from the poly(A) tail. The level of access to the 5' cap and poly(A) tail is important in controlling how soon the mRNA is degraded. PARN deadenylates less if the RNA is bound by the initiation factors 4E (at the 5' cap) and 4G (at the poly(A) tail), which is why translation reduces deadenylation. The rate of deadenylation may also be regulated by RNA-binding proteins. Once the poly(A) tail is removed, the decapping complex removes the 5' cap, leading to a degradation of the RNA. Several other enzymes that seem to be involved in deadenylation have been identified in yeast.

Alternative polyadenylation[modifica]

Molts dels gens codificants de proteïnes tenen més d'un lloc de poliadenilació, de manera que un gen pot codificar per a diversos mRNAs que difereixen en el seu extrem 3']].[24][45][46] La Despoliadenilació alternativa canvia la longitud de la regió 3' no traduïda, es pot canviar perquè els llocs de microARN la regió no traduïda 3' UTR conté l'enllaç. .[16][47] els microARNs tendeixen a reprimir la traducció i promoure la degradació dels ARNm que s'uneixen a, encara que hi ha exemples de microARN que estabilitzen transcripcions.[48][49] poliadenilació alternativa també pot escurçar la regió de codificació, el que fa el codi d'ARNm per a una proteïna diferent,[50][51] però això és molt menys comú que acaba d'escurçar la regió no traduïda 3' .[24]

Many protein-coding genes have more than one polyadenylation site, so a gene can code for several mRNAs that differ in their 3' end Since alternative polyadenylation changes the length of the 3' untranslated region, it can change which binding sites for microRNAs the 3' untranslated region containsMicroRNAs tend to repress translation and promote degradation of the mRNAs they bind to, although there are examples of microRNAs that stabilise transcriptsAlternative polyadenylation can also shorten the coding region, thus making the mRNA code for a different proteinbut this is much less common than just shortening the 3' untranslated region

L'elecció del lloc de poli(A) pot ser influenciat per estímuls extracel·lulars i depèn de l'expressió de les proteïnes que participen en la poliadenilació.[52][53] Per exemple, l'expressió de CSTF - 64, una subunitat d'escissió de factor estimulant (CstF), augmenta en els macròfags en resposta als lipopolisacàrids (un grup de compostos bacterianes que desencadenen una resposta immune). Això resulta en la selecció de llocs de poli feble (A) i les transcripcions d'aquesta manera més curts. Això elimina elements reguladors en les regions 3' no traduïdes dels ARNm dels productes relacionats amb la defensa, com la lisozima i TNF - α. Aquests ARNm a continuació, tenen vides mitjanes més llargues i produeixen més d'aquestes proteïnes.[52] proteïnes d'unió d'ARN - diferents dels de la maquinària de poliadenilació també poden afectar si un lloc polyadenyation s'utilitza,[54][55][56][57] com pot metilació de l'ADN prop del senyal de poliadenilació.[58]

The choice of poly(A) site can be influenced by extracellular stimuli and depends on the expression of the proteins that take part in polyadenylationFor example, the expression of CstF-64, a subunit of cleavage stimulatory factor (), increases in macrophages in response to lipopolysaccharides (a group of bacterial compounds that trigger an immune response). This results in the selection of weak poly(A) sites and thus shorter transcripts. This removes regulatory elements in the 3' untranslated regions of mRNAs for defense-related products like lysozyme and TNF-α. These mRNAs then have longer half-lives and produce more of these proteinsRNA-binding proteins other than those in the polyadenylation machinery can also affect whether a polyadenyation site is usedas can DNA methylation near the polyadenylation signal

Cytoplasmic polyadenylation[modifica]

There is polyadenylation in the cytosol of some animal cell types, namely in the germ line, during early embryogenesis and in post-synaptic sites of nerve cells. This lengthens the poly(A) tail of an mRNA with a shortened poly(A) tail, so that the mRNA will be translated.[40][59] These shortened poly(A) tails are often less than 20 nucleotides, and are lengthened to around 80–150 nucleotides.[3]

No és de poliadenilació en el citosol d'alguns tipus de cèl·lules animals, és a dir, en la línia germinal, durant l'embriogènesi primerenca i en llocs postsinàptics de les cèl·lules nervioses. Això allarga la cua poli(A) d'un ARNm amb un poli escurçat (A) de cua, de manera que l'ARNm es tradueix. [ 40 ] [ 59 ] Aquests poli escurçat (A) les cues són sovint menys de 20 nucleòtids, i estan allargats al voltant de 80-150 nucleòtids. [ 3 ]

En l'embrió primerenc de ratolí, poliadenilació citoplasmàtica d'ARN maternes de la cèl·lula ou permet a la cèl·lula per sobreviure i créixer tot i que la transcripció no s'inicia fins que el mitjà de l'etapa de 2 cèl·lules (etapa 4 en cèl·lules en l'ésser humà). [ 60 ] [ 61 ] en el cervell, la poliadenilació citoplasmàtica està actiu durant l'aprenentatge i podria tenir un paper en la potenciació a llarg termini, que és l'enfortiment de la transmissió de senyals d'una cèl·lula nerviosa a una altra en resposta als impulsos nerviosos i és important per a l'aprenentatge i la formació de la memòria. [ 3] [ 62 ]

Poliadenilació citoplasmàtica requereix la CPSF proteïnes d'unió d'ARN - i CPEB, i pot involucrar altres proteïnes d'unió a l'ARN com pumilio. [ 63 ] Depenent del tipus de cèl·lula, la polimerasa pot ser el mateix tipus de polimerasa de poliadenilat (PAP) que es fa servir en el procés nuclear, o la polimerasa. GLD -2 citoplasmàtica [ 64 ]

In the early mouse embryo, cytoplasmic polyadenylation of maternal RNAs from the egg cell allows the cell to survive and grow even though transcription does not start until the middle of the 2-cell stage (4-cell stage in human).[60][61] In the brain, cytoplasmic polyadenylation is active during learning and could play a role in long-term potentiation, which is the strengthening of the signal transmission from a nerve cell to another in response to nerve impulses and is important for learning and memory formation.[3][62]

Cytoplasmic polyadenylation requires the RNA-binding proteins CPSF and CPEB, and can involve other RNA-binding proteins like Pumilio.[63] Depending on the cell type, the polymerase can be the same type of polyadenylate polymerase (PAP) that is used in the nuclear process, or the cytoplasmic polymerase GLD-2.[64]

Tagging for degradation in eukaryotes[modifica]

Per a molts ARN no codificants, incloent ARNt, ARNr, ARNsn, i snoRNA, de poliadenilació és una forma de marcar l'ARN de la degradació, en almenys el llevat. [65] Aquest poliadenilació es realitza en el nucli pel complex TRAMP, que afegeix una cua que és de prop de 40 nucleòtids de llarg a l'extrem 3'. [66] l'ARN es degrada a continuació, pel exosoma. [67] Poli cues (a) també s'han trobat en fragments d'ARNr humans, tant la forma de homopolimérica (Un només) i heterpolymeric (majoritàriament) les cues A. [68]

For many non-coding RNAs, including tRNA, rRNA, snRNA, and snoRNA, polyadenylation is a way of marking the RNA for degradation, in at least yeast.[65] This polyadenylation is done in the nucleus by the TRAMP complex, which adds a tail that is around 40 nucleotides long to the 3' end.[66] The RNA is then degraded by the exosome.[67] Poly(A) tails have also been found on human rRNA fragments, both the form of homopolymeric (A only) and heterpolymeric (mostly A) tails.[68]

En procariotes i organuls[modifica]

En molts bacteris, ambdós ARNm i ARN no codificants poden ser poliadenilats. Aquesta cua de poli(A) promou la degradació per la degradosoma, que conté dos enzims d'ARN de degradació : polinucleòtid fosforilasa i RNasa E. polinucleòtid fosforilasa s'uneix a l'extrem 3' de l'ARN i l'extensió 3' proporcionada per la cua de poli(A) permet a s'uneixen als ARN l'estructura secundària d'una altra manera bloquejar l'extrem 3'. Les rondes successives de poliadenilació i la degradació de l'extrem 3' pel polinucleòtid fosforilasa permet la degradosome per superar aquestes estructures secundàries. El cua de poli(A) també pot reclutar RNases que tallen l'ARN en dos. [ 69 ] Aquests cues de poli (A) bacteriana són aproximadament 30 nucleòtids de longitud.[69]

En la mesura en diferents grups com els animals i els tripanosomes, els mitocondris contenen tant l'estabilització i desestabilització poli(A) cua. Objectius de poliadenilació desestabilitzadores tant d'ARNm i ARN no codificants. Els poli(A) les cues són 43 nucleòtids de llarg de mitjana. Els estabilitzadors comencen al codó de parada, i sense ells el codó de terminació (UAA) no està complet, ja que el genoma codifica només la part U o UA. Mitocondris de plantes només han desestabilitzar poliadenilació, i el mitocondri de llevat no tenen poliadenilació en absolut. [ 71 ]

Mentre que molts bacteris i mitocondris tenen polimerases poliadenilat, també tenen un altre tipus de poliadenilació, realitzat per si mateix polinucleòtid fosforilasa. Aquest enzim es troba en els bacteris, [ 72 ] mitocòndris, [ 73 ] plastidis [ 74 ] i com un constituent de la exosoma archeal (en els arqueobacteris que tenen un exosoma). [ 75 ] Es pot sintetitzar una extensió 3' on la gran majoria de les bases són adenines. Com en bacteris, de poliadenilació per polinucleòtid fosforilasa promou la degradació de l'ARN en els plastidis [ 76 ] i probablement també arqueobacteris. [ 71 ]

In many bacteria, both mRNAs and non-coding RNAs can be polyadenylated. This poly(A) tail promotes degradation by the degradosome, which contains two RNA-degrading enzymes: polynucleotide phosphorylase and RNase E. Polynucleotide phosphorylase binds to the 3' end of RNAs and the 3' extension provided by the poly(A) tail allows it to bind to the RNAs whose secondary structure would otherwise block the 3' end. Successive rounds of polyadenylation and degradation of the 3' end by polynucleotide phosphorylase allows the degradosome to overcome these secondary structures. The poly(A) tail can also recruit RNases that cut the RNA in two.[70] These bacterial poly(A) tails are about 30 nucleotides long

In as different groups as animals and trypanosomes, the mitochondria contain both stabilising and destabilising poly(A) tails. Destabilising polyadenylation targets both mRNA and noncoding RNAs. The poly(A) tails are 43 nucleotides long on average. The stabilising ones start at the stop codon, and without them the stop codon (UAA) is not complete as the genome only encodes the U or UA part. Plant mitochondria have only destabilising polyadenylation, and yeast mitochondria have no polyadenylation at all.[71]

While many bacteria and mitochondria have polyadenylate polymerases, they also have another type of polyadenylation, performed by polynucleotide phosphorylase itself. This enzyme is found in bacteria,[72] mitochondria,[73] plastids[74] and as a constituent of the archeal exosome (in those archaea that have an exosome).[75] It can synthesise a 3' extension where the vast majority of the bases are adenines. Like in bacteria, polyadenylation by polynucleotide phosphorylase promotes degradation of the RNA in plastids[76] and likely also archaea.[71]

Evolució[modifica]

Encara que la poliadenilació s'observa en gairebé tots els organismes, no és universal.[77][78] No obstant això, l'àmplia distribució d'aquesta modificació i el fet que és present en els organismes dels tres dominis de la vida implica que l'últim ancestre comú universal de tots els organismes vius, es presumeix, tenia algun tipus de sistema de poliadenilació..[69] als pocs organismes no poliadenilat ARNm, el que implica que han perdut els seus mecanismes de poliadenilació durant l'evolució. Encara que no es coneixen exemples d'eucariotes que no tenen poliadenilació, els ARNm del bacteri Mycoplasma gallisepticum i l'arquea halotolerant Haloferax volcanii no tenen aquesta modificació.[79][80]

Although polyadenylation is seen in almost all organisms, it is not universalHowever, the wide distribution of this modification and the fact that it is present in organisms from all three domains of life implies that the last universal common ancestor of all living organisms, it is presumed, had some form of polyadenylation systemA few organisms do not polyadenylate mRNA, which implies that they have lost their polyadenylation machineries during evolution. Although no examples of eukaryotes that lack polyadenylation are known, mRNAs from the bacterium and the salt-tolerant archaean lack this modification

La més antiga és l'enzim polyadenylating polinucleòtid fosforilasa. Aquest enzim és part tant de la degradosome bacteriana i la archaeal exosome, [ 81 ] dos complexos estretament relacionats que reciclen ARN en nucleòtids. Aquest enzim degrada ARN atacant l'enllaç entre els 3' -la majoria de nucleòtids amb un fosfat, la ruptura d'un nucleòtid difosfat. Aquesta reacció és reversible, i pel que l'enzim també es pot estendre d'ARN amb més nucleòtids. La cua heteropolymeric afegida per polinucleòtid fosforilasa és molt rica en adenina. L'elecció de l'adenina és molt probablement el resultat de majors concentracions d'ADP que altres nucleòtids com a resultat de l'ús d'ATP com una moneda d'energia, pel que és més probable que s'incorpora en aquesta cua en les primeres formes de vida. S'ha suggerit que la participació de les cues d'adenina - rica en la degradació de l'ARN va portar a l'evolució posterior de les polimerases de poliadenilat (enzims que produeixen poli(A) no hi ha cues amb altres nucleòtids en ells). [ 82 ]

Polimerases poliadenilat no són tan antics. Han evolucionat per separat en ambdós bacteris i eucariotes de CCA - l'addició de l'enzim, que és l'enzim que completa els extrems 3' dels ARNt. El seu domini catalític és homòloga a la d'altres polimerases. [ 67 ] Es presumeix que la transferència horitzontal d'enzim bacteriana CCA - afegint als eucariotes permetre l'enzim CCA - afegint arqueobacteris - com per canviar la funció d'un poli(A) polimerasa. [ 70 ] Alguns llinatges, com arqueobacteris i cianobacteris, mai van evolucionar 1 poliadenilat polimerasa. [ 82 ]

The most ancient polyadenylating enzyme is polynucleotide phosphorylase. This enzyme is part of both the bacterial degradosome and the archaeal exosome,[81] two closely related complexes that recycle RNA into nucleotides. This enzyme degrades RNA by attacking the bond between the 3'-most nucleotides with a phosphate, breaking off a diphosphate nucleotide. This reaction is reversible, and so the enzyme can also extend RNA with more nucleotides. The heteropolymeric tail added by polynucleotide phosphorylase is very rich in adenine. The choice of adenine is most likely the result of higher ADP concentrations than other nucleotides as a result of using ATP as an energy currency, making it more likely to be incorporated in this tail in early lifeforms. It has been suggested that the involvement of adenine-rich tails in RNA degradation prompted the later evolution of polyadenylate polymerases (the enzymes that produce poly(A) tails with no other nucleotides in them).[82]

Polyadenylate polymerases are not as ancient. They have separately evolved in both bacteria and eukaryotes from CCA-adding enzyme, which is the enzyme that completes the 3' ends of tRNAs. Its catalytic domain is homologous to that of other polymerases.[67] It is presumed that the horizontal transfer of bacterial CCA-adding enzyme to eukaryotes allowed the archaeal-like CCA-adding enzyme to switch function to a poly(A) polymerase.[69] Some lineages, like archaea and cyanobacteria, never evolved a polyadenylate polymerase.[82]

Història[modifica]

La poliadenilació es va identificar primer el 1960 com una activitat enzimàtica en extractes fets de nuclis cel·lulars que podien polimeritzar ATP, però no d'ADP, en poliadenina.[83][84] Encara identificat en molts tipus de cèl·lules, aquesta activitat no tenia cap funció coneguda fins a 1971, quan el poli(A) seqüències van ser trobats en els ARNm.[85][86] L'única funció d'aquestes seqüències es va pensar en un principi com la protecció de l'extrem 3' de l'ARN de les nucleases, però més tard els papers específics de poliadenilació en es van identificar exportació nuclear i traducció. Les polimerases responsables de poliadenilació es van purificar primer i caracteritza en la dècada de 1960 i 1970, però es van descobrir el gran nombre de proteïnes accessòries que controlen aquest procés només en la dècada de 1990.[85]

Polyadenylation was first identified in 1960 as an enzymatic activity in extracts made from cell nuclei that could polymerise ATP, but not ADP, into polyadenineAlthough identified in many types of cells, this activity had no known function until 1971, when poly(A) sequences were found in mRNAsThe only function of these sequences was thought at first to be protection of the 3' end of the RNA from nucleases, but later the specific roles of polyadenylation in nuclear export and translation were identified. The polymerases responsible for polyadenylation were first purified and characterized in the 1960s and 1970s, but the large number of accessory proteins that control this process were discovered only in the early 1990s

Referències[modifica]

| A Wikimedia Commons hi ha contingut multimèdia relatiu a: Bestiasonica/Poliadenilació |

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 Proudfoot, Nick J.; Furger, Andre; Dye, Michael J. «Integrating mRNA Processing with Transcription». Cell, 108, 4, 2002, pàg. 501–12. DOI: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00617-7. PMID: 11909521.

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 Guhaniyogi, J; Brewer, G «Regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells». Gene, 265, 1–2, 2001, pàg. 11–23. DOI: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00350-X. PMID: 11255003.

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 3,2 Richter, Joel D. «Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation in Development and Beyond». Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 63, 2, 1999, pàg. 446–56. PMC: 98972. PMID: 10357857.

- ↑ Steege, Deborah A. «Emerging features of mRNA decay in bacteria». RNA, 6, 8, 2000, pàg. 1079–90. DOI: 10.1017/S1355838200001023. PMC: 1369983. PMID: 10943888.

- ↑ Anderson, James T. «RNA Turnover: Unexpected Consequences of Being Tailed». Current Biology, 15, 16, 2005, pàg. R635–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.002. PMID: 16111937.

- ↑ Stevens, A «Ribonucleic Acids-Biosynthesis and Degradation». Annual Review of Biochemistry, 32, 1963, pàg. 15–42. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.bi.32.070163.000311. PMID: 14140701.

- ↑ Principles of biochemistry. 2nd. Nova York: Worth, 1993. ISBN 978-0-87901-500-8.

- ↑ Abaza, I.; Gebauer, F. «Trading translation with RNA-binding proteins». RNA, 14, 3, 2008, pàg. 404–9. DOI: 10.1261/rna.848208. PMC: 2248257. PMID: 18212021.

- ↑ Mattick, J. S. «Non-coding RNA». Human Molecular Genetics, 15, 90001, 2006, pàg. R17–29. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddl046. PMID: 16651366.

- ↑ 10,0 10,1 Hunt, Arthur G; Xu, Ruqiang; Addepalli, Balasubrahmanyam; Rao, Suryadevara; Forbes, Kevin P; Meeks, Lisa R; Xing, Denghui; Mo, Min; Zhao, Hongwei «Arabidopsis mRNA polyadenylation machinery: comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions and gene expression profiling». BMC Genomics, 9, 2008, pàg. 220. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-220. PMC: 2391170. PMID: 18479511.

- ↑ 11,0 11,1 Davila Lopez, M.; Samuelsson, T. «Early evolution of histone mRNA 3' end processing». RNA, 14, 1, 2007, pàg. 1–10. DOI: 10.1261/rna.782308. PMC: 2151031. PMID: 17998288.

- ↑ Marzluff, William F.; Gongidi, Preetam; Woods, Keith R.; Jin, Jianping; Maltais, Lois J. «The Human and Mouse Replication-Dependent Histone Genes». Genomics, 80, 5, 2002, pàg. 487–98. DOI: 10.1016/S0888-7543(02)96850-3. PMID: 12408966.

- ↑ Saini, H. K.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Enright, A. J. «Genomic analysis of human microRNA transcripts». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 45, 2007, pàg. 17719–24. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0703890104.

- ↑ Yoshikawa, M. «A pathway for the biogenesis of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis». Genes & Development, 19, 18, 2005, pàg. 2164–75. DOI: 10.1101/gad.1352605. PMC: 1221887. PMID: 16131612.

- ↑ Amaral, Paulo P.; Mattick, John S. «Noncoding RNA in development». Mammalian Genome, 19, 7–8, 2008, pàg. 454–92. DOI: 10.1007/s00335-008-9136-7. PMID: 18839252.

- ↑ 16,0 16,1 Liu, D.; Brockman, J. M.; Dass, B.; Hutchins, L. N.; Singh, P.; McCarrey, J. R.; MacDonald, C. C.; Graber, J. H. «Systematic variation in mRNA 3'-processing signals during mouse spermatogenesis». Nucleic Acids Research, 35, 1, 2006, pàg. 234–46. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkl919. PMC: 1802579. PMID: 17158511.

- ↑ Lutz, Carol S. «Alternative Polyadenylation: A Twist on mRNA 3′ End Formation». ACS Chemical Biology, 3, 10, 2008, pàg. 609–17. DOI: 10.1021/cb800138w. PMID: 18817380.

- ↑ 18,0 18,1 Beaudoing, E.; Freier, S; Wyatt, JR; Claverie, JM; Gautheret, D «Patterns of Variant Polyadenylation Signal Usage in Human Genes». Genome Research, 10, 7, 2000, pàg. 1001–10. DOI: 10.1101/gr.10.7.1001. PMC: 310884. PMID: 10899149.

- ↑ Brown, Kirk M; Gilmartin, Gregory M «A Mechanism for the Regulation of Pre-mRNA 3′ Processing by Human Cleavage Factor Im». Molecular Cell, 12, 6, 2003, pàg. 1467–76. DOI: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00453-2. PMID: 14690600.

- ↑ Yang, Q.; Gilmartin, G. M.; Doublie, S. «Structural basis of UGUA recognition by the Nudix protein CFIm25 and implications for a regulatory role in mRNA 3' processing». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 22, 2010, pàg. 10062–7. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1000848107.

- ↑ Yang, Qin; Coseno, Molly; Gilmartin, Gregory M.; Doublié, Sylvie «Crystal Structure of a Human Cleavage Factor CFIm25/CFIm68/RNA Complex Provides an Insight into Poly(A) Site Recognition and RNA Looping». Structure, 19, 3, 2011, pàg. 368–77. DOI: 10.1016/j.str.2010.12.021. PMC: 3056899. PMID: 21295486.

- ↑ Venkataraman, K. «Analysis of a noncanonical poly(A) site reveals a tripartite mechanism for vertebrate poly(A) site recognition». Genes & Development, 19, 11, 2005, pàg. 1315–27. DOI: 10.1101/gad.1298605. PMC: 1142555. PMID: 15937220.

- ↑ 23,0 23,1 Millevoi, Stefania; Loulergue, Clarisse; Dettwiler, Sabine; Karaa, Sarah Zeïneb; Keller, Walter; Antoniou, Michael; Vagner, StéPhan «An interaction between U2AF 65 and CF Im links the splicing and 3′ end processing machineries». The EMBO Journal, 25, 20, 2006, pàg. 4854–64. DOI: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601331. PMC: 1618107. PMID: 17024186.

- ↑ 24,0 24,1 24,2 Shen, Y.; Ji, G.; Haas, B. J.; Wu, X.; Zheng, J.; Reese, G. J.; Li, Q. Q. «Genome level analysis of rice mRNA 3'-end processing signals and alternative polyadenylation». Nucleic Acids Research, 36, 9, 2008, pàg. 3150–61. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkn158. PMC: 2396415. PMID: 18411206.

- ↑ Glover-Cutter, Kira; Kim, Soojin; Espinosa, Joaquin; Bentley, David L «RNA polymerase II pauses and associates with pre-mRNA processing factors at both ends of genes». Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 15, 1, 2007, pàg. 71–8. DOI: 10.1038/nsmb1352.

- ↑ Molecular Biology of the Cell, Chapter 6, "From DNA to RNA". 4th edition. Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. New York: Garland Science; 2002.

- ↑ Stumpf, G.; Domdey, H. «Dependence of Yeast Pre-mRNA 3'-End Processing on CFT1: A Sequence Homolog of the Mammalian AAUAAA Binding Factor». Science, 274, 5292, 1996, pàg. 1517–20. DOI: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1517. PMID: 8929410.

- ↑ Iseli, C.; Stevenson, B. J.; De Souza, S. J.; Samaia, H. B.; Camargo, A. A.; Buetow, K. H.; Strausberg, R. L.; Simpson, A. J.G.; Bucher, P. «Long-Range Heterogeneity at the 3' Ends of Human mRNAs». Genome Research, 12, 7, 2002, pàg. 1068–74. DOI: 10.1101/gr.62002. PMC: 186619. PMID: 12097343.

- ↑ Balbo, Paul B.; Bohm, Andrew «Mechanism of Poly(A) Polymerase: Structure of the Enzyme-MgATP-RNA Ternary Complex and Kinetic Analysis». Structure, 15, 9, 2007, pàg. 1117–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.010. PMC: 2032019. PMID: 17850751.

- ↑ Viphakone, N.; Voisinet-Hakil, F.; Minvielle-Sebastia, L. «Molecular dissection of mRNA poly(A) tail length control in yeast». Nucleic Acids Research, 36, 7, 2008, pàg. 2418–33. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkn080. PMC: 2367721. PMID: 18304944.

- ↑ Wahle, Elmar «Poly(A) Tail Length Control Is Caused by Termination of Processive Synthesis». Journal of Biological Chemistry, 270, 6, 1995, pàg. 2800–8. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2800. PMID: 7852352.

- ↑ Dichtl, B.; Blank, D; Sadowski, M; Hübner, W; Weiser, S; Keller, W «Yhh1p/Cft1p directly links poly(A) site recognition and RNA polymerase II transcription termination». The EMBO Journal, 21, 15, 2002, pàg. 4125–35. DOI: 10.1093/emboj/cdf390. PMC: 126137. PMID: 12145212.

- ↑ Nag, Anita; Narsinh, Kazim; Martinson, Harold G «The poly(A)-dependent transcriptional pause is mediated by CPSF acting on the body of the polymerase». Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 14, 7, 2007, pàg. 662–9. DOI: 10.1038/nsmb1253.

- ↑ Ayalew Tefferi «Primer on medical genomics part II: Background principles and methods in molecular genetics». Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 77, 8, 31-08-2002, pàg. 785-808. DOI: 10.4065/77.8.785. PMID: 12173714 [Consulta: 1r novembre 2012].

- ↑ Coller, J. M.; Gray, N. K.; Wickens, M. P. «mRNA stabilization by poly(A) binding protein is independent of poly(A) and requires translation». Genes & Development, 12, 20, 1998, pàg. 3226–35. DOI: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3226.

- ↑ 36,0 36,1 Siddiqui, N.; Mangus, D. A.; Chang, T.-C.; Palermino, J.-M.; Shyu, A.-B.; Gehring, K. «Poly(A) Nuclease Interacts with the C-terminal Domain of Polyadenylate-binding Protein Domain from Poly(A)-binding Protein». Journal of Biological Chemistry, 282, 34, 2007, pàg. 25067–75. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M701256200. PMID: 17595167.

- ↑ Vinciguerra, Patrizia; Stutz, FrançOise «mRNA export: an assembly line from genes to nuclear pores». Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 16, 3, 2004, pàg. 285–92. DOI: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.013. PMID: 15145353.

- ↑ Gray, N. K.; Coller, JM; Dickson, KS; Wickens, M «Multiple portions of poly(A)-binding protein stimulate translation in vivo». The EMBO Journal, 19, 17, 2000, pàg. 4723–33. DOI: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4723. PMC: 302064. PMID: 10970864.

- ↑ Meaux, S.; Van Hoof, A «Yeast transcripts cleaved by an internal ribozyme provide new insight into the role of the cap and poly(A) tail in translation and mRNA decay». RNA, 12, 7, 2006, pàg. 1323–37. DOI: 10.1261/rna.46306. PMC: 1484436. PMID: 16714281.

- ↑ 40,0 40,1 Meijer, H. A.; Bushell, M.; Hill, K.; Gant, T. W.; Willis, A. E.; Jones, P.; De Moor, C. H. «A novel method for poly(A) fractionation reveals a large population of mRNAs with a short poly(A) tail in mammalian cells». Nucleic Acids Research, 35, 19, 2007, pàg. e132–e132. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkm830.

- ↑ Lehner, B.; Sanderson, CM «A Protein Interaction Framework for Human mRNA Degradation». Genome Research, 14, 7, 2004, pàg. 1315–23. DOI: 10.1101/gr.2122004. PMC: 442147. PMID: 15231747.

- ↑ Wu, L. «From the Cover: MicroRNAs direct rapid deadenylation of mRNA». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 11, 2006, pàg. 4034–9. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0510928103.

- ↑ Cui, J.; Sackton, K. L.; Horner, V. L.; Kumar, K. E.; Wolfner, M. F. «Wispy, the Drosophila Homolog of GLD-2, Is Required During Oogenesis and Egg Activation». Genetics, 178, 4, 2008, pàg. 2017–29. DOI: 10.1534/genetics.107.084558. PMC: 2323793. PMID: 18430932.

- ↑ Wilusz, Carol J.; Wormington, Michael; Peltz, Stuart W. «The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover». Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2, 4, 2001, pàg. 237–46. DOI: 10.1038/35067025. PMID: 11283721.

- ↑ Tian, B.; Hu, J; Zhang, H; Lutz, CS «A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes». Nucleic Acids Research, 33, 1, 2005, pàg. 201–12. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gki158. PMC: 546146. PMID: 15647503.

- ↑ Danckwardt, Sven; Hentze, Matthias W; Kulozik, Andreas E «3′ end mRNA processing: molecular mechanisms and implications for health and disease». The EMBO Journal, 27, 3, 2008, pàg. 482–98. DOI: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601932. PMC: 2241648. PMID: 18256699.

- ↑ Sandberg, R.; Neilson, J. R.; Sarma, A.; Sharp, P. A.; Burge, C. B. «Proliferating Cells Express mRNAs with Shortened 3' Untranslated Regions and Fewer MicroRNA Target Sites». Science, 320, 5883, 2008, pàg. 1643–7. DOI: 10.1126/science.1155390. PMC: 2587246. PMID: 18566288.

- ↑ Tili, Esmerina; Michaille, Jean-Jacques; Calin, George Adrian «Expression and function of micro-RNAs in immune cells during normal or disease state». International Journal of Medical Sciences, 5, 2, 2008, pàg. 73–9. PMC: 2288788. PMID: 18392144.

- ↑ Ghosh, T.; Soni, K.; Scaria, V.; Halimani, M.; Bhattacharjee, C.; Pillai, B. «MicroRNA-mediated up-regulation of an alternatively polyadenylated variant of the mouse cytoplasmic -actin gene». Nucleic Acids Research, 36, 19, 2008, pàg. 6318–32. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkn624. PMC: 2577349. PMID: 18835850.

- ↑ Alt, F; Bothwell, AL; Knapp, M; Siden, E; Mather, E; Koshland, M; Baltimore, D «Synthesis of secreted and membrane-bound immunoglobulin mu heavy chains is directed by mRNAs that differ at their 3′ ends». Cell, 20, 2, 1980, pàg. 293–301. DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90615-7. PMID: 6771018.

- ↑ Tian, B.; Pan, Z.; Lee, J. Y. «Widespread mRNA polyadenylation events in introns indicate dynamic interplay between polyadenylation and splicing». Genome Research, 17, 2, 2007, pàg. 156–65. DOI: 10.1101/gr.5532707. PMC: 1781347. PMID: 17210931.

- ↑ 52,0 52,1 Shell, S. A.; Hesse, C; Morris Jr, SM; Milcarek, C «Elevated Levels of the 64-kDa Cleavage Stimulatory Factor (CstF-64) in Lipopolysaccharide-stimulated Macrophages Influence Gene Expression and Induce Alternative Poly(A) Site Selection». Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280, 48, 2005, pàg. 39950–61. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M508848200. PMID: 16207706.

- ↑ Danckwardt, Sven; Gantzert, Anne-Susan; Macher-Goeppinger, Stephan; Probst, Hans Christian; Gentzel, Marc; Wilm, Matthias; Gröne, Hermann-Josef; Schirmacher, Peter; Hentze, Matthias W. «p38 MAPK Controls Prothrombin Expression by Regulated RNA 3′ End Processing». Molecular Cell, 41, 3, 2011, pàg. 298–310. DOI: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.032. PMID: 21292162.

- ↑ Licatalosi, Donny D.; Mele, Aldo; Fak, John J.; Ule, Jernej; Kayikci, Melis; Chi, Sung Wook; Clark, Tyson A.; Schweitzer, Anthony C.; Blume, John E. «HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing». Nature, 456, 7221, 2008, pàg. 464–9. DOI: 10.1038/nature07488. PMC: 2597294. PMID: 18978773.

- ↑ Hall-Pogar, T.; Liang, S.; Hague, L. K.; Lutz, C. S. «Specific trans-acting proteins interact with auxiliary RNA polyadenylation elements in the COX-2 3'-UTR». RNA, 13, 7, 2007, pàg. 1103–15. DOI: 10.1261/rna.577707. PMC: 1894925. PMID: 17507659.

- ↑ Danckwardt, Sven; Kaufmann, Isabelle; Gentzel, Marc; Foerstner, Konrad U; Gantzert, Anne-Susan; Gehring, Niels H; Neu-Yilik, Gabriele; Bork, Peer; Keller, Walter «Splicing factors stimulate polyadenylation via USEs at non-canonical 3′ end formation signals». The EMBO Journal, 26, 11, 2007, pàg. 2658–69. DOI: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601699. PMC: 1888663. PMID: 17464285.

- ↑ Danckwardt, Sven; Gantzert, Anne-Susan; Macher-Goeppinger, Stephan; Probst, Hans Christian; Gentzel, Marc; Wilm, Matthias; Gröne, Hermann-Josef; Schirmacher, Peter; Hentze, Matthias W. «p38 MAPK Controls Prothrombin Expression by Regulated RNA 3′ End Processing». Molecular Cell, 41, 3, 2011, pàg. 298–310. DOI: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.032. PMID: 21292162.

- ↑ Wood, A. J.; Schulz, R.; Woodfine, K.; Koltowska, K.; Beechey, C. V.; Peters, J.; Bourc'his, D.; Oakey, R. J. «Regulation of alternative polyadenylation by genomic imprinting». Genes & Development, 22, 9, 2008, pàg. 1141–6. DOI: 10.1101/gad.473408.

- ↑ Jung, M.-Y.; Lorenz, L.; Richter, J. D. «Translational Control by Neuroguidin, a Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4E and CPEB Binding Protein». Molecular and Cellular Biology, 26, 11, 2006, pàg. 4277–87. DOI: 10.1128/MCB.02470-05. PMC: 1489097. PMID: 16705177.

- ↑ Sakurai, Takayuki; Sato, Masahiro; Kimura, Minoru «Diverse patterns of poly(A) tail elongation and shortening of murine maternal mRNAs from fully grown oocyte to 2-cell embryo stages». Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 336, 4, 2005, pàg. 1181–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.250. PMID: 16169522.

- ↑ Taft, R «Virtues and limitations of the preimplantation mouse embryo as a model system». Theriogenology, 69, 1, 2008, pàg. 10–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.09.032. PMC: 2239213. PMID: 18023855.

- ↑ Richter, J «CPEB: a life in translation». Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 32, 6, 2007, pàg. 279–85. DOI: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.04.004. PMID: 17481902.

- ↑ Piqué, Maria; López, José Manuel; Foissac, Sylvain; Guigó, Roderic; Méndez, Raúl «A Combinatorial Code for CPE-Mediated Translational Control». Cell, 132, 3, 2008, pàg. 434–48. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.038. PMID: 18267074.

- ↑ Benoit, P.; Papin, C.; Kwak, J. E.; Wickens, M.; Simonelig, M. «PAP- and GLD-2-type poly(A) polymerases are required sequentially in cytoplasmic polyadenylation and oogenesis in Drosophila». Development, 135, 11, 2008, pàg. 1969–79. DOI: 10.1242/dev.021444. PMID: 18434412.

- ↑ Reinisch, Karin M; Wolin, Sandra L «Emerging themes in non-coding RNA quality control». Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 17, 2, 2007, pàg. 209–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.03.012. PMID: 17395456.

- ↑ Lacava, John; Houseley, Jonathan; Saveanu, Cosmin; Petfalski, Elisabeth; Thompson, Elizabeth; Jacquier, Alain; Tollervey, David «RNA Degradation by the Exosome Is Promoted by a Nuclear Polyadenylation Complex». Cell, 121, 5, 2005, pàg. 713–24. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.029. PMID: 15935758.

- ↑ 67,0 67,1 Martin, G.; Keller, W. «RNA-specific ribonucleotidyl transferases». RNA, 13, 11, 2007, pàg. 1834–49. DOI: 10.1261/rna.652807. PMC: 2040100. PMID: 17872511.

- ↑ Slomovic, S.; Laufer, D; Geiger, D; Schuster, G «Polyadenylation of ribosomal RNA in human cells». Nucleic Acids Research, 34, 10, 2006, pàg. 2966–75. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkl357. PMC: 1474067. PMID: 16738135.

- ↑ 69,0 69,1 69,2 Anantharaman, V.; Koonin, EV; Aravind, L «Comparative genomics and evolution of proteins involved in RNA metabolism». Nucleic Acids Research, 30, 7, 2002, pàg. 1427–64. DOI: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1427. PMC: 101826. PMID: 11917006.

- ↑ Régnier, Philippe; Arraiano, Cecília Maria «Degradation of mRNA in bacteria: emergence of ubiquitous features». BioEssays, 22, 3, 2000, pàg. 235–44. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200003)22:3<235::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-2. PMID: 10684583.

- ↑ 71,0 71,1 Slomovic, Shimyn; Portnoy, Victoria; Liveanu, Varda; Schuster, Gadi «RNA Polyadenylation in Prokaryotes and Organelles; Different Tails Tell Different Tales». Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 25, 2006, pàg. 65–77. DOI: 10.1080/07352680500391337.

- ↑ Chang, S. A.; Cozad, M.; MacKie, G. A.; Jones, G. H. «Kinetics of Polynucleotide Phosphorylase: Comparison of Enzymes from Streptomyces and Escherichia coli and Effects of Nucleoside Diphosphates». Journal of Bacteriology, 190, 1, 2007, pàg. 98–106. DOI: 10.1128/JB.00327-07. PMC: 2223728. PMID: 17965156.

- ↑ Nagaike, T; Suzuki, T; Ueda, T «Polyadenylation in mammalian mitochondria: Insights from recent studies». Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1779, 4, 2008, pàg. 266–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.02.001.

- ↑ Walter, M.; Kilian, J; Kudla, J «PNPase activity determines the efficiency of mRNA 3'-end processing, the degradation of tRNA and the extent of polyadenylation in chloroplasts». The EMBO Journal, 21, 24, 2002, pàg. 6905–14. DOI: 10.1093/emboj/cdf686. PMC: 139106. PMID: 12486011.

- ↑ Portnoy, V.; Schuster, G. «RNA polyadenylation and degradation in different Archaea; roles of the exosome and RNase R». Nucleic Acids Research, 34, 20, 2006, pàg. 5923–31. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkl763. PMC: 1635327. PMID: 17065466.

- ↑ Yehudai-Resheff, S. «Domain Analysis of the Chloroplast Polynucleotide Phosphorylase Reveals Discrete Functions in RNA Degradation, Polyadenylation, and Sequence Homology with Exosome Proteins». The Plant Cell Online, 15, 9, 2003, pàg. 2003–19. DOI: 10.1105/tpc.013326.

- ↑ Sarkar, Nilima «POLYADENYLATION OFmRNA IN PROKARYOTES». Annual Review of Biochemistry, 66, 1997, pàg. 173–97. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.173. PMID: 9242905.

- ↑ Slomovic, S; Portnoy, V; Schuster, G «RNA Turnover in Prokaryotes, Archaea and Organelles». Falta indicar la publicació, 447, 2008, pàg. 501–20. DOI: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02224-6.

- ↑ Portnoy, Victoria; Evguenieva-Hackenberg, Elena; Klein, Franziska; Walter, Pamela; Lorentzen, Esben; Klug, Gabriele; Schuster, Gadi «RNA polyadenylation in Archaea: not observed in Haloferax while the exosome polynucleotidylates RNA in Sulfolobus». EMBO Reports, 6, 12, 2005, pàg. 1188–93. DOI: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400571. PMC: 1369208. PMID: 16282984.

- ↑ Portnoy, Victoria; Schuster, Gadi «Mycoplasma gallisepticum as the first analyzed bacterium in which RNA is not polyadenylated». FEMS Microbiology Letters, 283, 1, 2008, pàg. 97–103. DOI: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01157.x. PMID: 18399989.

- ↑ Evguenieva-Hackenberg, Elena; Roppelt, Verena; Finsterseifer, Pamela; Klug, Gabriele «Rrp4 and Csl4 Are Needed for Efficient Degradation but Not for Polyadenylation of Synthetic and Natural RNA by the Archaeal Exosome†». Biochemistry, 47, 50, 2008, pàg. 13158–68. DOI: 10.1021/bi8012214. PMID: 19053279.

- ↑ 82,0 82,1 Slomovic, S; Portnoy, V; Yehudairesheff, S; Bronshtein, E; Schuster, G «Polynucleotide phosphorylase and the archaeal exosome as poly(A)-polymerases». Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1779, 4, 2008, pàg. 247–55. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.12.004.

- ↑ Edmonds, Mary; Abrams, Richard «Polynucleotide Biosynthesis: Formation of a Sequence of Adenylate Units from Adenosine Triphosphate by an Enzyme from Thymus Nuclei». The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 235, 4, 1960, pàg. 1142–9. PMID: 13819354.

- ↑ Colgan, D. F.; Manley, J. L. «Mechanism and regulation of mRNA polyadenylation». Genes & Development, 11, 21, 1997, pàg. 2755–66. DOI: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2755.

- ↑ 85,0 85,1 Edmonds, M «Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology Volume 71». Falta indicar la publicació, 71, 2002, pàg. 285–389. DOI: 10.1016/S0079-6603(02)71046-5.

- ↑ Edmonds, M. «Polyadenylic Acid Sequences in the Heterogeneous Nuclear RNA and Rapidly-Labeled Polyribosomal RNA of HeLa cells: Possible Evidence for a Precursor Relationship». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 68, 6, 1971, pàg. 1336–40. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1336.

Bibliografia complementària[modifica]

- Danckwardt, Sven; Hentze, Matthias W; Kulozik, Andreas E «3′ end mRNA processing: molecular mechanisms and implications for health and disease». The EMBO Journal, 27, 3, 2008, pàg. 482–98. DOI: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601932. PMC: 2241648. PMID: 18256699.

Categoria:ARN

Categoria:Processos cel·lulars

Categoria:Bioquímica

Categoria:Genètica molecular

Categoria:Biologia molecular