Usuari:Robertgarrigos/proves/Pla vèlic

|

|

Aquest article o secció s'està traduint a partir de: «Sail_plan» (anglès) en la versió del 27/8/2021, amb llicència CC-BY-SA Hi pot haver llacunes de contingut, errors sintàctics o escrits sense traduir. |

Un pla de vela és una descripció de les maneres específiques de com s'aparella una embarcació de vela. A més, el terme pla vèlic és una representació gràfica de la disposició de les veles per a una embarcació de vela determinada.[1]

Introducció[modifica]

Un pla vèlic ben dissenyat hauria de ser equilibrat, requerint poca força sobre el timó per mantenir la nau a rumb. Els plans vèlics on el centre de resistència estigui situat a proa o a popa del centre de resistència lateral de l'embarcació, la faran arribar (virar cap a sotavent) o orsar (virar cap a sobrevent) respectivament.[2] L'alçada del centre de resistència del pla vèlic per sobre de la superfície marina està limitada per l'habilitat del veler d'evitar la bolcada. Aquesta, ve determinada per la forma del casc, el llast o la distància entre cascs (en el cas dels vaixells de més d'un casc, com els catamarans i els trimarans).[3]

Tipus d'aparell[modifica]

- Aparell rodó: format per veles rodones o quadres.[4][5]

- Aparell de tall: format per veles de tall o triangulars.

- Aparell híbrid: format per veles rodones i de tall.[6]

Tipus de veles[modifica]

Les veles poden ser de dos tipus:

- Veles rodones o quadres: són de forma més o menys quadrada i es disposen de forma perpendicular a la línia de crugia del vaixell. Són veles que funcionen molt bé amb vents portants, que venen més o menys de popa.

- Veles de tall o triangulars: són de forma més o menys triangular i es disposen de forma més o menys paral·lela a la crugia del vaixell. Són veles que funcionen millor amb vents de cenyida, que venen més o menys de proa.

Pals i vergues[modifica]

Els vaixells de vela poden disposar d'un o més pals. En funció del nombre de pals, de la seva alçada i de la seva posició relativa, els pals reben un nom diferent:

- Major: nom del pal en vaixells d'un sol pal o el pal més alt en vaixells de dos o més pals.

- Trinquet: en vaixells de dos o més pals, és el pal més proper a proa, sempre que sigui menor que el pal major.

- Mitjana o messana: en vaixells de dos o més pals, és el pal més proper a popa, sempre que sigui menor que el pal major.

On a square-sailed vessel, the sails of each mast are named by the mast and position on the mast. For instance, on the mainmast (from bottom to top):

On many ships, sails above the top (a platform just above the lowest sail) were mounted on separate masts ("topmasts" or "topgallant masts") held in wooden sockets called "trestletrees". These masts and their stays could be rigged or struck as the weather conditions required, or for maintenance and repair.

In light breezes, the working square sails would be supplemented by studding sails ("stuns'l") out on the ends of the yardarms. These were called as a regular sail, with the addition of "studding". For example, the main top studding sail.

Between the main mast and mizzen as well as between main mast and foremast, the staysails between the masts are named from the sail immediately below the highest attachment point of the stay holding up that staysail. Thus, the mizzen topgallant staysail can be found dangling from the stay leading from above the mizzen (third) mast's topgallant sail (i.e., from the mizzen topgallant yard) to at least one and usually two sails down from that on the main mast (the slope of the top edge of all staysail lines runs from a higher point nearer the stern to a lower point towards the bow).

The jibs (the staysails between the foremast and the bowsprit) are named (from inner to outer most) fore topmast staysail (or foretop stay), inner jib, outer jib and flying jib. Many of the jibs' stays meet the foremast just above the fore topgallant. A fore royal staysail may also be set.

Types of sail plans[modifica]

Sail-plan gallery[modifica]

- sailplan

-

Proa: single mast with crab claw sail

-

Catboat: single mast sail, usually gunter- or gaff-rigged; found on dinghies.

-

Lugger: two-masted lug rig

-

Gunter: like a sloop with a short mast; the sail is bent on to both the mast and to a spar that is hoisted aloft to increase mainsail area.

-

Sloop: single mast with a mainsail and a jib. (Shown here with a gaff-rigged sail and topsail).

-

Cutter: single masted like a bermuda sloop, but with two or more headsails; may have gaff mainsail. (Square-sails are rare on a cutter).

-

Yawl: fore-and-aft rigged mainmast and mizzen mast aft of the tiller

-

Ketch: two fore-and-aft rigged masts, mizzen mast before the tiller

-

Schooner: two or more fore-and-aft rigged masts, first mast no taller than the second

-

Topsail schooner: two schooner-rigged masts with one or more square-rigged topsails

-

Bilander: two masts, main mast course sail lateen rigged, all others square rigged

-

Brig: two square-rigged masts and headsails

-

Schooner brig: one square-rigged foremast and one fore-and-aft rigged main mast

-

Brigantine: one square-rigged foremast and hybrid rigged main mast

-

Snow: headsails, two square-rigged masts, and a third smaller 'snow-mast' with a trysail

-

Barque: two or more square-rigged masts and headsails with fore-and-aft rigged aftmost mast

-

Barquentine: one square-rigged mast (fore) and two or more fore-and-aft rigged (main, mizzen, etc.) masts

-

Polacre: one square-rigged main with headsails and two lateen rigged aft masts

-

Fully rigged ship: three or more (all) square-rigged masts and headsails

-

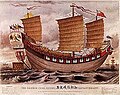

Junk rig: one or more junk-rigged masts

-

Felucca: one to three lateen rigged masts

Types of sails[modifica]

Quadrilateral sails[modifica]

- Quadrilateral

-

A square sail may be loose-footed, as shown here on a Viking longship.

-

A square sail may have a spar along the foot, as shown here on an ancient Egyptian vessel.

-

A lugsail has an asymmetric, quadrilateral shape.

-

A settee sail has an asymmetric, quadrilateral shape, approaching the triangular shape of a lateen sail.

-

A gaff rig sail is attached to a spar (gaff) along the top, a boom at the bottom, all of which are attached to the mast.

-

A spritsail has the peak of the sail supported by a diagonal sprit.

-

A gunter rig has a vertical spar that extends vertically above the mast.

-

A tanja sail is a fore-and-aft canted sail with spars on both the upper and lower edges

Triangular sails[modifica]

- Triangular

-

This Bermuda catboat has one side of the sail attached to the mast

-

A lateen is like a lugsail, but triangular. It is loose-footed.

-

A crabclaw sail is not loose-footed. It has spars along two sides. The Sunfish shown here is a crabclaw catboat with an unstayed mast.

Distinctions in nomenclature[modifica]

Plantilla:Unreferenced section

- Nomenclature

-

A four-masted barque, square-rigged on the first three masts. One or more fore-and-aft sails on the aftmost mast help a ship steer and turn.

-

A five-masted square-rigged ship. All the masts bear square sails.

-

A three-masted junk ship, an 800-ton trading vessel of the mid-1800s

-

A three-masted junk ship, more fore-and-aft than the 1800s junk

-

A felucca with three lateens. Feluccas with one or two are also possible.

European, and especially English, watercraft terminology draws a strong distinction between square-rigged vessels (with square sails hung from yards mounted centrally and horizontally from masts) and fore-and-aft rigged ones (everything else). It is important to note that any other sail (such as a lug or spritsail), even if it is geometrically square, is not a square sail in the technical sense used in European sail terminology. It is merely a quadrilateral fore-and-aft sail. Vessels are named by the number of square-rigged masts that they have. This is because square-rigged vessels used to be the fastest rig, and more masts were faster.

In the Austronesian regions of the Indo-Pacific, both large and small sailing vessels traditionally use what are generally called crab claw sails, although they are of many different types. Other indigenous sails were also developed by Austronesians, like the tanja and the junk sail. Western rigs were also introduced and used from during the colonial era.

Junk rigs essentially have the stack of sails, but without all the gaps between them. Where the yards controlled the towers of square sails, the battens controlled the junk sail. Although originally Southeast Asian, they have become the main sail used in East Asia after early adoption by the Chinese. All traditional East Asian vessels use junk sails, and vessels are not named by sail type, but by region, function, and other characteristics.

In the Middle East, on the east coast of Africa, and as far east as India, lateens and settees were in common use. Ships were named more with regard to purpose than number of masts or type of sail. For instance, feluccas and sambuks were mostly used for fishing and ferrying, dhows are heavy cargo vessels. Xebecs, which also had oars, were used by corsairs to outpace merchant vessels, which were also often xebecs.

Attempts to blend nomenclature, as in the junk diagram to the left above, occur. A ship can be rigged with one of its sails as a junk sail and another as a Bermuda rig without being considered a junk vessel.

Catboat (one mast, one sail)[modifica]

A catboat is a sailboat with a single mast and single sail; for examples of the variety of catboats, see the section above. This is the easiest sail plan to sail, and is used on the smallest and simplest boats. The catboat is a classic fishing boat. A popular movement for home-built boats uses this simple rig to make "folk-boats".

The term "catboat" is usually qualified by the type of sail, for example, "a gaff catboat".

Austronesian vessels[modifica]

-

Traditional Austronesian generalized sail types. C, D, E, and F are types of crab claw sails. G, H, and I are tanja sails.[9]

A Double sprit (Sri Lanka)

B Common sprit (Philippines)

C Oceanic sprit (Tahiti)

D Oceanic sprit (Marquesas)

E Oceanic sprit (Philippines)

F Crane sprit (Marshall Islands)

G Rectangular boom lug (Maluku Islands)

H Square boom lug (Gulf of Thailand)

I Trapezial boom lug (Vietnam)

The seafaring Austronesian peoples independently developed various sail types during the Neolithic, beginning with the crab claw sail (also misleadingly called the "oceanic lateen" or the "oceanic sprit") at around 1500 BCE. They are used throughout the range of the Austronesian Expansion, from Maritime Southeast Asia, to Micronesia, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar. Crab claw sails are rigged fore-and-aft and can be tilted and rotated relative to the wind. They evolved from "V"-shaped perpendicular square sails in which the two spars converge at the base of the hull. The simplest form of the crab claw sail (also with the widest distribution) is composed of a triangular sail supported by two light spars (sometimes erroneously called "sprits") on each side. They were originally mastless, and the entire assembly was taken down when the sails were lowered.[10]

-

Melanesian V-shaped square sail

-

New Zealand V-shaped square sail

-

Hawaiian crab claw sail with the upper spar merged with the fixed mast

Austronesian rigs were used for double-canoe (catamaran), single-outrigger (on the windward side), or double-outrigger boat configurations, in addition to monohulls.[11][12] There are several distinct types of crab claw rigs, but unlike western rigs, they do not have fixed conventional names.[13]

The need to propel larger and more heavily-laden boats led to the increase in vertical sail. However this introduced more instability to the vessels. In addition to the unique invention of outriggers to solve this, the sails were also leaned backwards and the converging point moved further forward on the hull. This new configuration required a loose "prop" in the middle of the hull to hold the spars up, as well as rope supports on the windward side. This allowed more sail area (and thus more power) while keeping the center of effort low and thus making the boats more stable. The prop was later converted into fixed or removable canted masts where the spars of the sails were actually suspended by a halyard from the masthead. This type of sail is most refined in Micronesian proas which could reach very high speeds. These configurations are sometimes known as the "crane sprit" or the "crane spritsail". Micronesian, Island Melanesian, and Polynesian single-outrigger vessels also used this canted mast configuration to uniquely develop shunting, where canoes are symmetrical from front to back and change end-to-end when sailing against the wind.[10][13]

The conversion of the prop to a fixed mast led to the much later invention of the tanja sail (also known variously and misleadingly as the canted square sail, canted rectangular sail, boomed lugsail, or balance lugsail). Tanja sails were rigged similarly to crab claw sails and also had spars on both the head and the foot of the sails; but they were square or rectangular with the spars not converging into a point.[10][13]

Another evolution of the basic crab claw sail is the conversion of the upper spar into a fixed mast. In Polynesia, this gave the sail more height while also making it narrower, giving it a shape reminiscent of crab pincers (hence "crab claw" sail). This was also usually accompanied by the lower spar becoming more curved.[10][13]

Proa[modifica]

-

Pacific proa, on a beam reach rightwards, with the wind blowing into the page.

-

Atlantic proa. Note that the wind is on the other side, blowing out of the page.

The vessel known as the "proa" (or more accurately the "Pacific proa") in western terminology is more accurately a single-outrigger Austronesian boat with one sail (typified by vessels like the Chamorro sakman). Both ends are alike, and the boat is sailed in either direction, but it has a fixed leeward side and a windward side. The boat is shunted from beam reach to beam reach to change direction, with the wind over the side, a low-force procedure. The bottom corner of the crabclaw sail is moved to the other end, which becomes the bow as the boat sets off back the way it came. The mast usually hinges, adjusting its rake (mast). The proa is a low-stress rig, which can be built with simple tools and low-tech materials, but it is extremely fast. On a beam reach, it may be the fastest simple rig.

In a traditional Pacific proa, the outrigger (ama) lies on the windward side of the main hull (vaka), with its weight helping keep the proa upright. The ama is very thin, to punch through waves, smoothing the ride. The first Europeans, building proas from travelers' reports, built Atlantic proas, with the outrigger on the leeward side, with its buoyancy keeping the proa upright.

"To be clear, we can blame Richard C. Newick for the debate" (about racing proas), "since it was he who came up with the Atlantic proa in the first place, with his groundbreaking Cheers – the “giant killer” that came in third in the 1968 OSTAR. Unlike all proas until Cheers, Newick placed the ama to lee and the rig to windward, concentrating all the ballast to windward and thus multiplying the righting moment."[14]

The term "proa" was also historically used for other types of Austronesian vessels with different rigs, with or without outriggers.

Junk[modifica]

-

Typical junk rig

Junk rigs were originally made from woven mats reinforced with bamboo, from at least several hundred years BCE. They were Austronesian in origin but were later adopted by the Chinese after contact with Southeast Asian traders (K'un-lun po) by the time of the Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE).[15][16][17]

In its most traditional form the junk rig is carried on an unstayed mast (i.e. a mast without shrouds or stays, supported only on the step at the keelson and the partners); however, standing rigging of some kind is not uncommon. It is typical to run the halyards (lines used to raise and lower the sail) and sheets (lines used to trim the sail) to the companionway on a junk-rigged boat. This means that typical sailhandling can be performed from the relative safety of the cockpit, or even while the crew is below deck.

Junk sails are typically carried on a mast which rakes (slants) forward a few degrees from vertical. The forward rake of the sail encourages the sail to swing out, which makes the use of a preventer unnecessary. Another way to say this is that the sail is stable when swung out and doesn't return to the middle of the ship when the wind drops.

Sloop (one mast, two sails)[modifica]

-

Gunter-rigged sloop. The sail shape is intermediate between Bermuda and gaff sails.

-

Gaff-rigged sloop with a headsail and a gaff topsail.

-

Spritsail sloop

A Bermuda or gaff mainsail lifted by a single mast with a single jib attached to a bowsprit, bent onto the forestay, held taut with a backstay. The mainsail is usually managed with a spar on the underside called a "boom".

A Bermuda-rigged sloop is one of the best racing rigs per square foot of sail area as is it very weatherly, making it faster on upwind passages. This rig is the most popular for recreational boating because of its potential for high performance. On small boats, it can be a simple rig. On larger sloops, the large sails have high loads, and one must manage them with winches or multiple purchase block-and-tackle devices.

Cutter (one mast, two or more foresails)[modifica]

-

Gaff cutter with a gaff sail (the quadrilateral one below the gaff), two headsails, and a gaff topsail above the gaff.

-

Naval cutter with a square topsail hoisted. It also has a gaff sail aft, and two headsails. It is not currently carrying a gaff topsail, though it might use one when going upwind.

A small single-masted ship with three or more sails. A common rig is a gaff-rigged mainsail, multiple headsails, and, often, a gaff- or square-rigged topsail above. Sometimes cutters also had an additional square-rigged mainsail when traveling downwind. The mast was normally set amidships, and two or more headsails were set from the mast to the running bowsprit.[18] Considered better than a sloop for light winds; it is also easier to manage, as the sail area is more subdivided.

Multi-masted vessels[modifica]

Schooner[modifica]

A fore-and-aft rig having at least two masts, the foremast normally being shorter than the others. The rig is rarely found on a hull of less than 50 feet LOA, and small schooners are generally two-masted. In the two decades around 1900, larger multi-masted schooners were built in New England and on the Great Lakes with four, five, six, or even, seven masts.[19]:239-242 Schooners were traditionally gaff-rigged, and some schooners sailing today are reproductions of famous schooners of old, but modern vessels tend to be Bermuda rigged (or occasionally junk-rigged).[20] While a sloop rig is simpler and cheaper, the schooner rig may be chosen on a larger boat so as to reduce the overall mast height and to keep each sail to a more manageable size, giving a mainsail that is easier to handle and to reef. An issue when planning a two-masted schooner's rig is how to fill the space between the masts: for instance, one may adopt (i) a gaff sail on the foremast (even with a bermuda mainsail), or (ii) a main staysail, often with a fisherman topsail to fill the gap at the top in light airs.

Topsail schooner[modifica]

A topsail schooner also has a square topsail on the foremast, to which may be added a topgallant and other square sails, but not a fore course, as that would make the vessel a brigantine.[b] A lower yard (to which a course, if it were used, would be attached) is still needed to carry the sheets of the square topsail. The fore and aft sails are as for any other schooner.[22]:26 The square sails improve downwind performance.

Lugger[modifica]

A lugger is usually a two or three masted vessel, setting lug sails on each mast.[c] A jib or staysail may be set on some luggers. More rarely, lug topsails are used by some luggers – notably the chasse-marée. A lug sail is an asymmetric quadrilateral sail that fastens to a yard (spar) along the head (top edge) of the sail. The yard is held to the mast either by a parrel or by a traveller (consisting of a metal ring that goes round the mast and has an eye for the halyard and a hook which fastens to a strop on the yard). A dipping lug sail is fastened at the tack (front lower corner) some distance in front of the mast. A standing lug's tack is fastened near the foot of the mast. The halyard for a dipping lug is usually made fast to the weather gunwale, thereby allowing the mast to be unstayed. A common arrangement is to have a dipping lug foresail and a standing lug mizzen.[d] This arrangement is found on many traditional British fishing vessels, such as the fifie - but there are examples of dipping lugs on two masts or standing lugs on all of 2 or 3 masts (as in the chasse-marée).[23]:15-27, 62-70[25]:36

A standing lug may be used with or without a boom; most working craft were boomless to allow more working space. The dipping lug never uses a boom. A dipping lug has to be moved to the leeward side of the mast when going about, so that the sail can take a good aerodynamic shape on the new tack. There are several methods of doing this – one of which is to simply lower the sail, manhandle the yard and sail to the other side of the mast and re-hoist. All the various methods are time and labour consuming. A standing lug can be left unaltered when tacking as it still sets reasonably well with the sail pressed against the mast.[25](p36) Some users (such as in the Royal Navy Montagu whaler) would still dip the yard of a standing lug (with a sharp, well timed downward pull on the leech at the moment when the wind is not filling the sail). Conversely many fishermen would always hoist a standing lug on the same side of the mast regardless of which tack they expected to be sailing on.

Sailing performance with a standing lug relies on the right amount of luff tension. An essential component of this rig is the tack tackle, a purchase with which luff tension is adjusted for various points of sail.[25]:34

The balanced (or balance) lug has a boom that projects in front of the mast roughly the same distance as the yard. This is generally used in dinghies. The sail is left on the same side of the mast regardless of the wind direction. A downhaul is set up from the boom to a point close to the heel of the mast and its adjustment is critical to getting this sort of sail to set correctly.[25]:37

Two-masted vessels[modifica]

Ketch[modifica]

A small ship with two masts, both fore-and-aft rigged, with the mizzen located well forward of the rudder post and of only slightly smaller size than the mainmast (if the height of the masts were reversed—the taller in the back and the shorter in the front—it would be considered a schooner). If square-rigged on her mainmast above the course, it is called a "square topsail ketch". Historically the mainmast was square-rigged instead of fore-and-aft, but in modern usage only the latter is called a ketch. The purpose of the mizzen sail in a ketch rig, unlike the mizzen on a yawl rig, is to provide drive to the hull. A ketch rig allows for shorter sails than a sloop with the same sail area, resulting in a lower center of sail and less overturning moment. The shorter masts, therefore, reduce the amount of ballast and stress on the rigging needed to keep the boat upright. Generally the rig is safer and less prone to broaching or capsize than a comparable sloop, and has more flexibility in sail plan when reducing sail under strong crosswind conditions—the mainsail can be brought down entirely (not requiring reefing) and the remaining rig will be both balanced on the helm and capable of driving the boat. The ketch is a classic small cargo boat.

Yawl[modifica]

A small ship, fore-and-aft rigged on its two masts, with its mainmast much taller than its mizzen and with or without headsails. The mizzen mast is located aft of the rudderpost, sometimes directly on the transom, and is intended to help provide helm balance.

Bilander[modifica]

The bilander is a two-masted vessel, the foremast carrying square rigs on all of its yards and its taller mainmast having a long lateen mainsail yard with corresponding trapezoidal sail and rig inclined at about 45° with square rigs on the yards above that, the lowermost secured at the corners by a crossjack. The design was popular in the Mediterranean Sea as well as around New England in the first half of the 18th century but was soon surpassed by better designs. It is considered the forerunner of the brig.[26]

Brig[modifica]

In American parlance, the brig encompasses three classes of ship: the full-rigged brig (often simply called a "brig"), the hermaphrodite brig, and the brigantine. All American brigs are defined by having exactly two masts that are entirely or partially square-rigged. The foremast of each is always entirely square-rigged; variations in the taller mainmast are what define the different subtypes[26] (The definition of a brig, brigantine, etc. has been subject to variations in nation and history, however, with much crossover between the classes).

Full-rigged brig[modifica]

For the full-rigged brig, the foremast and mainmast each has three spars, all of them square rigged. In addition, the mainmast has a small gaff-rigged sail mounted behind ("abaft") the mainmast.

Hermaphrodite brig[modifica]

On a hermaphrodite brig, also called a "half brig" and a "schooner brig", the main mast carries no yards: it is made in two spars and carries two sails, a gaff mainsail and gaff topsail, making it half schooner and half brig (hence its name). If it also carries one or more square-rigged topsails on the mainmast, it is then considered a "jackass brig".[26] Some authors have asserted that this type of sail plan is that of a brigantine.[27]

Brigantine[modifica]

Like the hermaphrodite brig, a brigantine also has a main (second) mast made in two spars, and its large mainsail is also fore and aft rigged. However, above this it carries two or three square-rigged yards instead of a gaff topsail (the hermaphrodite brig retains the gaff topsail), and carries no square-rigged sail at all on its lowermost yard of its mainmast (the full-rigged brig retains a square-rigged sail in this position, making it very difficult to visually distinguish at a distance from a brigantine).[26]

Snow[modifica]

Although superficially similar in appearance to the brig or brigantine, the snow is a much older three masted design which evolved from the larger fully rigged ship. The foremast and mainmast are both square-rigged, but the fore and aft rigged spanker sail is attached to a small trysail mast (or in modern times a steel cable) stepped directly behind the mainmast. This "snow-mast" allows the gaff to be raised unhindered by the mainmast and higher than the main yard, which in turn also allows the snow to set a main course without complications.

Three-masted vessels[modifica]

Barque[modifica]

Three masts or more, square rigged on all except the aftmost mast. Usually three or four-masted, but five-masted barques have been built. Lower-speed than a full-rigged ship, especially downwind, but requiring fewer sailors than a full-rigged ship. Optimum rig for transoceanic voyages. This is a classic windjammer rig.

Barquentine or Schooner Barque[modifica]

Three masts or more, square-rigged on the foremast and fore-and-aft rigged on the main and mizzen masts.

Polacre[modifica]

A three master with a narrow hull, carrying a square-rigged foremast, followed by two lateen sails. The same vessel, if she substituted her square-rigged mast with another lateen rigged one, would be called a xebec.

Fully rigged or ship-rigged ship[modifica]

Three or more masts, square-rigged on all, usually with stay-sails between masts. Occasionally the mizzen mast of a ship-rigged ship would have a fore-and-aft sail as its course sail (top image), but in order to qualify as a "fully rigged ship" the vessel would need to have a square-rigged topsail mounted above this (thus distinguishing the fully rigged ship from, say, a barque—see above). The classic ship rig (top) originally had exactly three masts, but later, four- and five-masted ships were also built (bottom). The classic sailing warship—the ship of the line—was full rigged in this way, because of high performance on all points of wind. In particular, studding sails or topping sails could be easily added for light airs or high speeds. Square rigs have twice the sail area per mast height compared to triangular sails, and when tuned, more exactly approximate a multiple airfoil, and therefore apply larger forces to the hull. Windage (drag) is more than triangular rigs, which have smaller tip vortices. Therefore, historic ships could not point as far upwind as high-performance sloops. However, contemporary Marconi rigs (sloops, etc.) were limited in size by the strength of available materials, especially their sails and the running rigging to set them. Ships were not so limited, because their sails were smaller relative to the hull, distributing forces more evenly, over more masts. Therefore, due to their much larger, longer waterline length, ships had much faster hull speeds and could run down or away from any contemporary sloop or other Marconi rig, even if it pointed more upwind. Schooners have a heavier rig and require more ballast than ships, which increases the wetted area and hull friction of a large schooner compared to a ship of the same size. The result is that a ship can run down or away from a schooner of the same hull length. Ships were larger than brigs and brigantines, and faster than barques or barquentines, but required more sailors. Also called "ship-rigged".

Sail-plan measurements[modifica]

Every sail plan has maximum dimensions.[Cal aclariment][28][29] These maxima are for the largest sail possible and they are defined by a letter abbreviation.

- J The base of the foretriangle measured along the deck from the forestay pin to the front of the mast.

- I The height measured along the front of mast from the jib halyard to the deck.

- E The foot length of the mainsail along the boom.

- P The luff length of the mainsail measured along the aft of the mast from the top of the boom to the highest point that the mainsail can be hoisted at the top of the mast.

- Ey The length of a second boom (For a Ketch or Yawl).

- Py The height of the second mast from the boom to the top of the mast.

See also[modifica]

Notes[modifica]

- ↑ Since the early nineteenth century, the topsails and topgallants are often split into a lower and an upper sail to allow them to be more easily handled. This makes the mast appear to have more "sails" than it officially has.

- ↑ Maritime terminology is often not precise, varying over time and place. Some vessels carrying a forecourse were described as schooners by their owners, crews and others. A more complex (and now obsolete) definition of a schooner (where square rig was carried) considered whether the foremast is made in the same way as a square-rigged mast, with a lower mast, topmast and royal mast.[21]:39-41, 135, 136

- ↑ There are some single-masted lug-rigged craft that are referred to as luggers, including the New Orleans Lugger (or Oyster Lugger).[23]:358–363

- ↑ Because 2 masted traditional British luggers were often derived from earlier 3 masted versions, the forward mast on these 2 masted vessels was called the foremast and the after mast the mizzen. It was the main mast that had been dispensed with.[23]:120[24]:19

Referències[modifica]

- ↑ > Folkard, Henry Coleman. Sailing Boats from Around the World: The Classic 1906 Treatise. Courier Corporation, 2012, p. 576 (Dover Maritime). ISBN 9780486311340.

- ↑ Pla i Bartina, Joaquim. Lleugera idea dels principis teòrics de la propulsió a vela (Veles de tall) (en català). Girona: Càtedra d’Estudis Marítims (Universitat de Girona i Ajuntament de Palamós) i Museu de la Pesca, 2004, p. 14. ISBN 84-933396-3-6.

- ↑ Killing, Steve; Hunter, Douglas. Yacht Design Explained: A Sailor's Guide to the Principles and Practice of Design (en anglès). W. W. Norton & Company, 1998, p. 153. ISBN 978-0-393-04646-5.

- ↑ Mates, M. La Devota peregrinacio de la Terra Sancta y civtat de Hiervsalem (en castellà). en la estampa de Gabriel Graells y Giraldo Dotil, 1604, p. 5-IA1.

- ↑ DCVB: Caire.

- ↑ Pla i Bartina, Joaquim. Els vaixells mercants d’aparell llatí a la Marina Catalana Segles XVIII, XIX i XX (en català). Girona: Càtedra d’Estudis Marítims (Universitat de Girona – Fundació Promediterrània) Museu de la Pesca, 2016, p. 74.

- ↑ Underhill, Harold. Sailing Ship Rigs and Rigging. Glasgow: Brown, Son and Ferguson, Ltd, 1955.

- ↑ «Calling The Wind of Reunion». Vaka.org, 02-01-2017. [Consulta: 3 gener 2018].

- ↑ Doran, Edwin B. Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press, 1981. ISBN 9780890961070.

- ↑ 10,0 10,1 10,2 10,3 Campbell, I.C. «The Lateen Sail in World History». Journal of World History, vol. 6, 1, 1995, pàg. 1–23. JSTOR: 20078617.

- ↑ Horridge, Adrian. «Origins and Relationships of Pacific Canoes and Rigs». A: Di Piazza, Anne. Canoes of the Grand Ocean. Archaeopress, 2008 (BAR International Series 1802). ISBN 9781407302898.

- ↑ {{{títol}}} (tesi).

- ↑ 13,0 13,1 13,2 13,3 Horridge, Adrian «The Evolution of Pacific Canoe Rigs». The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 21, 2, April 1986, pàg. 83–99. DOI: 10.1080/00223348608572530. JSTOR: 25168892.

- ↑ «Proa File – Discussion Forum». ProaFile.com. [Consulta: 3 gener 2018].

- ↑ Shaffer, Lynda Norene (1996). Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. M.E. Sharpe.

- ↑ Johnstone, Paul. The Seacraft of Prehistory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, p. 93–4. ISBN 978-0674795952.

- ↑ Hourani, George Fadlo. Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1951.

- ↑ Nicholas Blake. The Illustrated Companion to Nelson's Navy. Stackpole, August 2005, p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8117-3275-8.

- ↑ Leather, John. Gaff Rig. London: Adlard Coles Limited, 1970. ISBN 0-229-97489-9.

- ↑ Images of junk-rigged schooners – [1]

- ↑ MacGregor, David R. Schooners in Four Centuries. Hemel Hempstead: Argus Books Ltd., 1982. ISBN 0-85242-774-3.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Tom. Hand, Reef and Steer: Traditional Sailing Skills for Classic. second. Adlard Coles, 2016. ISBN 978-1472925220.

- ↑ 23,0 23,1 23,2 Leather, John. Spritsails and Lugsails. 1989 reissue. Camden, Maine: International Marine Publishing Company, 1979. ISBN 0877429987.

- ↑ March, Edgar J. Sailing Drifters: The Story of the Herring Luggers of England, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Newton Abbott: David & Charles, 1969. ISBN 0-7153-4679-2.

- ↑ 25,0 25,1 25,2 25,3 Barnes, Roger. The Dinghy Cruising Companion: Tales and Advice from Sailing in a Small Open Boat. Kindle. Oxford: Adlard Coles, 2014. ISBN 978-1408179161.

- ↑ 26,0 26,1 26,2 26,3 John Robinson. The Sailing Ships of New England, 1607–1907. Marine Research Society, 1922, p. 28–30.

- ↑ John Harper. Ghostly Tales on Land and Sea. F+W Media, 30 November 2010, p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4463-5004-1.

- ↑ «Sail Measurement Assistance». www.SecondWindSails.com. [Consulta: 3 gener 2018].

- ↑ «hoodsailmakers.com». www.HoodSailMakers.com. [Consulta: 3 gener 2018].

Further reading[modifica]

- Bolger, Philip C.. 103 Sailing Rigs "Straight Talk". Gloucester, Maine: Phil Bolger & Friends, Inc, 1998. ISBN 0-9666995-0-5.

Enllaços externs[modifica]

| A Wikimedia Commons hi ha contingut multimèdia relatiu a: Robertgarrigos/proves/Pla vèlic |

Plantilla:Sailing vessels and rigs Plantilla:Sail Types

![This tepukei has crab-claw sails.[8] The cut-away side helps a sudden gust of wind escape without ripping the sail.[cal citació]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/Sail_plan_tepukei.svg/116px-Sail_plan_tepukei.svg.png)

![Traditional Austronesian generalized sail types. C, D, E, and F are types of crab claw sails. G, H, and I are tanja sails.[9] A Double sprit (Sri Lanka) B Common sprit (Philippines) C Oceanic sprit (Tahiti) D Oceanic sprit (Marquesas) E Oceanic sprit (Philippines) F Crane sprit (Marshall Islands) G Rectangular boom lug (Maluku Islands) H Square boom lug (Gulf of Thailand) I Trapezial boom lug (Vietnam)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Austronesian_Sail_Types.png/300px-Austronesian_Sail_Types.png)