Història de la malària: diferència entre les revisions

Cap resum de modificació |

|||

| Línia 17: | Línia 17: | ||

Cap a finals del segle XX, la malària romania endèmica en més de 100 països en les zones tropicals i subtropicals, incloent grans àrees de Centre i Sud Amèrica, L'Espanyola (Haití i República Dominicana), Àfrica, Orient Mitjà, el subcontinent indi , el sud-est d'Àsia i Oceania. La resistència del [[Plasmodi]] als medicaments contra la malària, així com la resistència dels mosquits als insecticides i el descobriment d'espècies [[Zoonosis|zoonòtiques]] del paràsit han complicat les mesures de control. |

Cap a finals del segle XX, la malària romania endèmica en més de 100 països en les zones tropicals i subtropicals, incloent grans àrees de Centre i Sud Amèrica, L'Espanyola (Haití i República Dominicana), Àfrica, Orient Mitjà, el subcontinent indi , el sud-est d'Àsia i Oceania. La resistència del [[Plasmodi]] als medicaments contra la malària, així com la resistència dels mosquits als insecticides i el descobriment d'espècies [[Zoonosis|zoonòtiques]] del paràsit han complicat les mesures de control. |

||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

{{TOC limit|3}} |

||

== Origen i període prehistòric == |

|||

[[File:Baltic_Amber_necklace_with_insects_inclusions.jpg|thumb|right|The mosquito and the [[fly]] in this [[Baltic Sea|Baltic]] amber necklace are between 40 and 60 million years old.]] |

|||

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in [[mosquito]]es preserved in [[amber]] from the [[Paleogene|Palaeogene period]] that are approximately 30 million years old.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Poinar G |title=Plasmodium dominicana n. sp. (Plasmodiidae: Haemospororida) from Tertiary Dominican amber |journal=Syst. Parasitol. |volume=61 |issue=1 |pages=47–52 |year=2005 |pmid=15928991 |doi=10.1007/s11230-004-6354-6}}</ref> Human malaria likely originated in Africa and [[coevolution|coevolved]] with its hosts, mosquitoes and non-human [[primate]]s. Malaria protozoa are diversified into primate, rodent, bird, and reptile host lineages.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Joy DA, Feng X, Mu J, Furuya T, Chotivanich K, Krettli AU, Ho M, Wang A, White NJ, Suh E, Beerli P, Su XZ.| title = Early origin and recent expansion of Plasmodium falciparum | journal = Science | volume = 300 | issue = 5617 | pages = 318–21 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12690197 | doi = 10.1126/science.1081449}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Hayakawa T, Culleton R, Otani H, Horii T, Tanabe K| title = Big bang in the evolution of extant malaria parasites | journal = Mol Biol Evol | volume = 25 | issue = 10 | pages = 2233–9| year = 2008 | pmid = 18687771 | url = http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/25/10/2233 | doi = 10.1093/molbev/msn171 }}</ref> Humans may have originally caught ''[[Plasmodium falciparum]]'' from [[gorilla]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Liu W, Li Y, Learn GH, Rudicell RS, Robertson JD, Keele BF, Ndjango J-BN, Sanz CM, Morgan DB, Locatelli S, Gonder MK, Kranzusch PJ, Walsh PD, Delaporte E, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Georgiev AV, Muller MN, Shaw GW, Peeters M, Sharp PM, Julian C. Rayner JC & Hahn BH |title= Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas|journal= Nature |volume=467 |issue=7314 |pages=420–5 |year=2010 |pmid=20864995 |doi=10.1038/nature09442 |pmc=2997044}}</ref> ''[[Plasmodium vivax|P. vivax]]'', another malarial ''Plasmodium'' species among the six that infect humans, also likely originated in African [[gorilla]]s and [[chimpanzee]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Liu W, etal |title=African origin of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax|journal=Nature Communications|date=21 February 2014|issue=5 | url = http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140221/ncomms4346/full/ncomms4346.html|doi=10.1038/ncomms4346 |volume=5}}</ref> Another malarial species recently discovered to be transmissible to humans, ''[[Plasmodium knowlesi|P. knowlesi]]'', originated in Asian [[macaque monkey]]s.<ref>{{cite journal|author =Lee KS, Divis PC, Zakaria SK, Matusop A, Julin RA, Conway DJ, Cox-Singh J, Singh B |title= Plasmodium knowlesi: reservoir hosts and tracking the emergence in humans and macaques. |journal = PLoS Pathog |year= 2011| issue=4 | url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3072369/pdf/ppat.1002015.pdf |pmc=3072369 |pmid=21490952 |doi=10.1371/journal.ppat.1002015 |volume=7 |pages=e1002015}}</ref> While ''[[Plasmodium malariae|P. malariae]]'' is highly host specific to humans, there is spotty evidence that low level non-symptomatic infection persists among wild chimpanzees.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Hayakawa|first=Toshiyuki|title=Identification of Plasmodium malariae, a human malaria parasite, in imported chimpanzees|date=2009|volume=4|issue=10|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0007412|pmid=19823579|pmc=2756624|display-authors=etal|journal=PLoS ONE|pages=e7412}}</ref> |

|||

About 10,000 years ago, malaria started having a major impact on human survival, coinciding with the start of agriculture in the [[Neolithic revolution]]. Consequences included [[natural selection]] for [[sickle-cell disease]], [[thalassaemias]], [[glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency]], [[Southeast Asian ovalocytosis]], [[elliptocytosis]] and loss of the Gerbich antigen ([[glycophorin C]]) and the [[Duffy antigen system|Duffy antigen]] on the [[red blood cells|erythrocytes]], because such [[blood disorders]] confer a selective advantage against malaria infection ([[balancing selection]]).<ref>{{cite journal | author = Canali S| title = Researches on thalassemia and malaria in Italy and the origins of the "Haldane hypothesis"| journal = Med Secoli| volume =20 | issue =3| pages = 827–46| year =2008 | pmid = 19848219 | url = https://www.researchgate.net/publication/38028954_Researches_on_thalassemia_and_malaria_in_Italy_and_the_origins_of_the_Haldane_hypothesis}}</ref> The three major types of inherited [[Genetic resistance to malaria|genetic resistance]] (sickle-cell disease, thalassaemias, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency) were present in the [[Mediterranean]] world by the time of the [[Roman Empire]], about 2000 years ago.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Sallares R, Bouwman A, Anderung C | title = The Spread of Malaria to Southern Europe in Antiquity: New Approaches to Old Problems | journal = Med Hist| volume = 48 | issue = 3 | pages = 311–28| year = 2004 | pmid = 16021928 | pmc=547919 | doi=10.1017/s0025727300007651}}</ref> |

|||

Molecular methods have confirmed the high prevalence of ''P. falciparum'' malaria in [[ancient Egypt]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Brier B| title = Infectious diseases in ancient Egypt | journal = Infect Dis Clin North Am| year = 2004 | pmid = 15081501 | doi = 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00097-7 | volume = 18 | pages = 17–27 | issue = 1}}<br/>{{cite journal | author = Nerlich AG, Schraut B, Dittrich S, Jelinek T, Zink AR. | title = Plasmodium falciparum in Ancient Egypt| journal = Emerg Infect Dis | volume = 14 | pages =1317–9 | year = 2008 | pmid =18680669 |url = http://www.cdc.gov/eid/content/14/8/1317.htm | doi = 10.3201/eid1408.080235 | issue = 8 | pmc = 2600410 }}</ref> The [[Ancient Greek]] historian [[Herodotus]] wrote that the builders of the Egyptian [[pyramids]] (circa 2700 - 1700 BCE) were given large amounts of [[garlic]],<ref>{{cite journal | author = Macaulay GC| title = The History of Herodotus, parallel English/Greek translation | year = 1890 | pages = Herodotus, 2.125| url = http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/hh/hh2120.htm }}</ref> probably to protect them against malaria. The [[Pharaoh]] [[Sneferu]], the founder of the [[Fourth dynasty of Egypt]], who reigned from around 2613 – 2589 BCE, used [[mosquito net|bed-nets]] as protection against mosquitoes. [[Cleopatra VII]], the last Pharaoh of [[Ancient Egypt]], similarly slept under a mosquito net.<ref name = "malariasite">{{Cite web|url = http://www.malariasite.com/malaria/history_control.htm|title = History of Malaria Control| accessdate = 2009-10-27}}</ref> The presence of malaria in [[Egypt]] from circa 800 BCE onwards has been confirmed using [[DNA]]-based methods.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Lalremruata A, Ball M, Bianucci R, Welte B, Nerlich AG, Kun JF, Pusch CM | title = Molecular identification of falciparum malaria and human tuberculosis co-infections in mummies from the Fayum depression (lower Egypt) | journal = PLoS One 8(4):e60307 | pmc=3614933 | pmid=23565222 | doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0060307 | volume=8 | issue=4 | year=2013 | pages=e60307}}</ref> |

|||

== Referències == |

== Referències == |

||

Revisió del 23:05, 3 gen 2016

|

|

Aquest article o secció s'està elaborant i està inacabat. L'usuari MALLUS hi està treballant i és possible que trobeu defectes de contingut o de forma. Comenteu abans els canvis majors per coordinar-los. Aquest avís és temporal: es pot treure o substituir per {{incomplet}} després d'uns dies d'inactivitat. |

La història de la malària s'estén des del seu origen prehistòric com a malaltia zoonòtica en els primats d'Àfrica fins al segle XXI. Com a malaltia infecciosa humana generalitzada i potencialment letal, en el seu apogeu la malària ha infestat tots els continents, a excepció de l'Antàrtida.[1] Diversos científics i revistes científiques, incloent Nature i National Geographic, han teoritzat que la malària pot haver mort al voltant o per sobre de la meitat de tots els éssers humans que han viscut.[2][3][4][5][6][7] La seva prevenció i tractament han estat l'objectiu de la ciència i la medicina durant centenars d'anys. Des del descobriment dels paràsits que la causen, l'atenció de la investigació s'ha centrat en la seva biologia, així com la dels mosquits que transmeten els paràsits.

Els factors més crítics en la propagació o l'eradicació de la malaltia han estat el comportament humà (centres de població canviants, el canvi dels mètodes de cultiu i similars) i els nivells de vida. No existeixen estadístiques precises a causa de que molts dels casos ocorren en les zones rurals, on la gent no té accés als hospitals o a la salut. Com a conseqüència, la majoria dels casos no estan documentats.[8]La pobresa ha estat i segueix estant associada amb la malaltia.[9]

Les referències a les seves febres úniques, periòdiques es troben en tota la història registrada i comencen el 2700 aC a la Xina.[10]

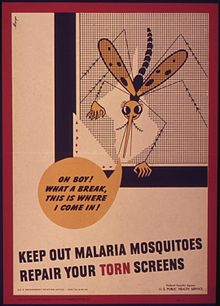

Durant milers d'anys, s'han utilitzat remeis herbals tradicionals per tractar la malària.[11] El primer tractament eficaç per a la malària prové de l'escorça de l'arbre de la quina, que conté quinina. Després que es va identificar l'enllaç als mosquits i els seus paràsits a principis del segle XX, es van iniciar les mesures de control de mosquits, com ara l'ús generalitzat del DDT, el drenatge dels pantans, el revestiment o greixatge de la superfície de les fonts d'aigua obertes, la fumigació d'interiors i l'ús de mosquiteres insecticides tractades. La quinina profilàctica va ser prescrita en zones endèmiques de malària, i es van utilitzar noves drogues terapèutiques, incloent la cloroquina i les artemisines, per resistir el flagell.

Els investigadors de la malària han guanyat múltiples premis Nobel pels seus èxits, tot i que la malaltia segueix afectant uns 200 milions de pacients cada any, i mata a més de 600.000.

La malària era el perill per a la salut més important trobat per les tropes nord-americanes al Pacífic Sud durant la Segona Guerra Mundial, on es van infectar uns 500.000 homes.[12]Segons Joseph Patrick Byrne, "Seixanta mil soldats nord-americans van morir de malària durant les campanyes d'Àfrica i Sud del Pacífic."[13]

Cap a finals del segle XX, la malària romania endèmica en més de 100 països en les zones tropicals i subtropicals, incloent grans àrees de Centre i Sud Amèrica, L'Espanyola (Haití i República Dominicana), Àfrica, Orient Mitjà, el subcontinent indi , el sud-est d'Àsia i Oceania. La resistència del Plasmodi als medicaments contra la malària, així com la resistència dels mosquits als insecticides i el descobriment d'espècies zoonòtiques del paràsit han complicat les mesures de control.

Origen i període prehistòric

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in mosquitoes preserved in amber from the Palaeogene period that are approximately 30 million years old.[14] Human malaria likely originated in Africa and coevolved with its hosts, mosquitoes and non-human primates. Malaria protozoa are diversified into primate, rodent, bird, and reptile host lineages.[15][16] Humans may have originally caught Plasmodium falciparum from gorillas.[17] P. vivax, another malarial Plasmodium species among the six that infect humans, also likely originated in African gorillas and chimpanzees.[18] Another malarial species recently discovered to be transmissible to humans, P. knowlesi, originated in Asian macaque monkeys.[19] While P. malariae is highly host specific to humans, there is spotty evidence that low level non-symptomatic infection persists among wild chimpanzees.[20]

About 10,000 years ago, malaria started having a major impact on human survival, coinciding with the start of agriculture in the Neolithic revolution. Consequences included natural selection for sickle-cell disease, thalassaemias, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, Southeast Asian ovalocytosis, elliptocytosis and loss of the Gerbich antigen (glycophorin C) and the Duffy antigen on the erythrocytes, because such blood disorders confer a selective advantage against malaria infection (balancing selection).[21] The three major types of inherited genetic resistance (sickle-cell disease, thalassaemias, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency) were present in the Mediterranean world by the time of the Roman Empire, about 2000 years ago.[22]

Molecular methods have confirmed the high prevalence of P. falciparum malaria in ancient Egypt.[23] The Ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote that the builders of the Egyptian pyramids (circa 2700 - 1700 BCE) were given large amounts of garlic,[24] probably to protect them against malaria. The Pharaoh Sneferu, the founder of the Fourth dynasty of Egypt, who reigned from around 2613 – 2589 BCE, used bed-nets as protection against mosquitoes. Cleopatra VII, the last Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, similarly slept under a mosquito net.[25] The presence of malaria in Egypt from circa 800 BCE onwards has been confirmed using DNA-based methods.[26]

Referències

- ↑ Carter R, Mendis KN «Evolutionary and historical aspects of the burden of malaria». Clin Microbiol Rev, vol. 15, 4, 2002, pàg. 564–94. DOI: 10.1128/cmr.15.4.564-594.2002. PMC: 126857. PMID: 12364370.

- ↑ Portrait of a killer, Nature News, "Malaria may have killed half of all the people that ever lived."

- ↑ Malaria, National Geographic Magazine, "Alguns científics creuen que una de cada dues persones que han viscut han mort de malària."

- ↑ The Tenacious Buzz of Malaria, The Wall Street Journal, "El paràsit de la malària ha estat responsable de la meitat de totes les morts humanes des de l'Edat de Pedra,"

- ↑ How scientists will win the war against malarial mosquitoes, IO9 (blog revisat per parells), George Dvorsky, "Els mosquits [de la malària] han matat més de la meitat de tots els éssers humans que han viscut"

- ↑ Brain Fuel, Joe Schwarcz, "... malaria, la terrible malaltia que ha matat a prop de la meitat dels éssers humans que han viscut," p.184

- ↑ Bio-inspired Innovation and National Security, Centre de Tecnologia i Política de Seguretat Nacional (Universitat de Defensa Nacional), "La malària és l'agent biològic, que alguns creuen que és responsable de la mort de la meitat de tots els éssers humans que han viscut," p.157

- ↑ Murray CJ, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS, Andrews KG, Foreman KJ, Haring D, Fullman N, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Lopez AD «Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis». Lancet, vol. 379, 9814, 2012, pàg. 413–431. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60034-8. PMID: 22305225.

- ↑ Worrall E, Basu S, Hanson K «Is malaria a disease of poverty? A review of the literature». Trop Med Int Health., vol. 10, 10, 2005, pàg. 1047–59. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01476.x. PMID: 16185240.

- ↑ Neghina R, Neghina AM, Marincu I, Iacobiciu I «Malaria, a Journey in Time: In Search of the Lost Myths and Forgotten Stories». Am J Med Sci, vol. 340, 6, 2010, pàg. 492–498. DOI: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e7fe6c. PMID: 20601857.

- ↑ Willcox ML, Bodeker G «Traditional herbal medicines for malaria». BMJ, vol. 329, 7475, 2004, pàg. 1156–9. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1156. PMC: 527695. PMID: 15539672.

- ↑ Bray RS. Armies of Pestilence: The Effects of Pandemics on History. James Clarke, 2004, p. 102. ISBN 978-0-227-17240-7.

- ↑ Byrne JP. Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO, 2008, p. 383. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1.

- ↑ Poinar G «Plasmodium dominicana n. sp. (Plasmodiidae: Haemospororida) from Tertiary Dominican amber». Syst. Parasitol., vol. 61, 1, 2005, pàg. 47–52. DOI: 10.1007/s11230-004-6354-6. PMID: 15928991.

- ↑ Joy DA, Feng X, Mu J, Furuya T, Chotivanich K, Krettli AU, Ho M, Wang A, White NJ, Suh E, Beerli P, Su XZ. «Early origin and recent expansion of Plasmodium falciparum». Science, vol. 300, 5617, 2003, pàg. 318–21. DOI: 10.1126/science.1081449. PMID: 12690197.

- ↑ Hayakawa T, Culleton R, Otani H, Horii T, Tanabe K «Big bang in the evolution of extant malaria parasites». Mol Biol Evol, vol. 25, 10, 2008, pàg. 2233–9. DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msn171. PMID: 18687771.

- ↑ Liu W, Li Y, Learn GH, Rudicell RS, Robertson JD, Keele BF, Ndjango J-BN, Sanz CM, Morgan DB, Locatelli S, Gonder MK, Kranzusch PJ, Walsh PD, Delaporte E, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Georgiev AV, Muller MN, Shaw GW, Peeters M, Sharp PM, Julian C. Rayner JC & Hahn BH «Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas». Nature, vol. 467, 7314, 2010, pàg. 420–5. DOI: 10.1038/nature09442. PMC: 2997044. PMID: 20864995.

- ↑ «African origin of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax». Nature Communications, vol. 5, 5, 21-02-2014. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms4346.

- ↑ Lee KS, Divis PC, Zakaria SK, Matusop A, Julin RA, Conway DJ, Cox-Singh J, Singh B «Plasmodium knowlesi: reservoir hosts and tracking the emergence in humans and macaques.». PLoS Pathog, vol. 7, 4, 2011, pàg. e1002015. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002015. PMC: 3072369. PMID: 21490952.

- ↑ Hayakawa, Toshiyuki «Identification of Plasmodium malariae, a human malaria parasite, in imported chimpanzees». PLoS ONE, vol. 4, 10, 2009, pàg. e7412. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007412. PMC: 2756624. PMID: 19823579.

- ↑ Canali S «Researches on thalassemia and malaria in Italy and the origins of the "Haldane hypothesis"». Med Secoli, vol. 20, 3, 2008, pàg. 827–46. PMID: 19848219.

- ↑ Sallares R, Bouwman A, Anderung C «The Spread of Malaria to Southern Europe in Antiquity: New Approaches to Old Problems». Med Hist, vol. 48, 3, 2004, pàg. 311–28. DOI: 10.1017/s0025727300007651. PMC: 547919. PMID: 16021928.

- ↑ Brier B «Infectious diseases in ancient Egypt». Infect Dis Clin North Am, vol. 18, 1, 2004, pàg. 17–27. DOI: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00097-7. PMID: 15081501.

Nerlich AG, Schraut B, Dittrich S, Jelinek T, Zink AR. «Plasmodium falciparum in Ancient Egypt». Emerg Infect Dis, vol. 14, 8, 2008, pàg. 1317–9. DOI: 10.3201/eid1408.080235. PMC: 2600410. PMID: 18680669. - ↑ Macaulay GC «The History of Herodotus, parallel English/Greek translation». , 1890, pàg. Herodotus, 2.125.

- ↑ «History of Malaria Control». [Consulta: 27 octubre 2009].

- ↑ Lalremruata A, Ball M, Bianucci R, Welte B, Nerlich AG, Kun JF, Pusch CM «Molecular identification of falciparum malaria and human tuberculosis co-infections in mummies from the Fayum depression (lower Egypt)». PLoS One 8(4):e60307, vol. 8, 4, 2013, pàg. e60307. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060307. PMC: 3614933. PMID: 23565222.