Usuari:Albert SN/Anells de Saturn

.

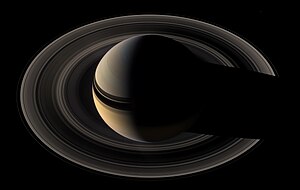

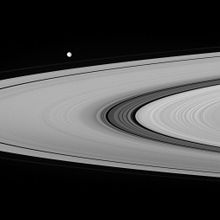

Els anells de Saturn són el sistema d'anells més extens de qualsevol planeta del Sistema solar. Consten d'innombrables partícules petites, que van des de micròmetres fins a metres,[1] que orbiten al voltant de Saturn. Les partícules de l'anell estan fetes gairebé totalment de gel d'aigua, amb un component traça de material rocós. Encara no hi ha consens sobre el seu mecanisme de formació. Tot i que els models teòrics indicaven que probablement els anells s'haguessin format a principis de la història del Sistema solar,[2] dades més noves de Cassiniva suggerir que es van formar relativament tard.[3]

Encara que la reflexió dels anells augmenta la brillantor de Saturn, no són visibles des de la Terra amb visió sense ajuda. El 1610, l'any després que Galileu Galilei girés un telescopi cap al cel, es va convertir en la primera persona a observar els anells de Saturn, tot i que no els va poder veure prou bé per discernir la seva veritable naturalesa. El 1655, Christiaan Huygens va ser la primera persona que els va descriure com un disc que envoltava Saturn.[4] El concepte que els anells de Saturn estan formats per una sèrie de petits anells es pot remuntar a Pierre-Simon Laplace,[4] encara que els buits reals són pocs; és més correcte pensar en els anells com un disc anular amb màxims i mínims locals concèntrics en densitat i lluminositat.[2] A l'escala dels grups dins dels anells hi ha molt espai buit.

Els anells tenen nombrosos buits on la densitat de partícules disminueix bruscament: dos oberts per llunes conegudes incrustades dins d'ells, i molts altres en llocs de ressonàncies orbitals desestabilitzadores conegudes amb els satèl·lits de Saturn. Altres llacunes continuen sense explicar-se. Les ressonàncies estabilitzadores, en canvi, són les responsables de la longevitat de diversos anells, com l'anell de Tità i l'anell G.

Molt més enllà dels anells principals hi ha l'anell de febe, que se suposa que prové de Febe i, per tant, comparteix el seu moviment orbital retrògrad. Està alineat amb el pla de l'òrbita de Saturn. Saturn té una inclinació axial de 27 graus, de manera que aquest anell està inclinat en un angle de 27 graus respecte als anells més visibles que orbiten per sobre de l'equador de Saturn.

Història

[modifica]Primeres observacions

[modifica]

Galileo Galilei va ser el primer a observar els anells de Saturn el 1610 amb el seu telescopi, però no els va poder identificar com a tals. Va escriure al duc de Toscana que "El planeta Saturn no està sol, sinó que està compost per tres, que gairebé es toquen i mai es mouen ni canvien l'un respecte a l'altre. Es disposen en una línia paral·lela al zodíac, i el del mig (el mateix Saturn) és aproximadament tres vegades més gran que els laterals."[5] També va descriure els anells com les "orelles" de Saturn. L'any 1612 la Terra va passar pel pla dels anells i es van fer invisibles. Desconcertat, Galileu va comentar: "No sé què dir en un cas tan sorprenent, tan inesperat i tan nou".[5] Va reflexionar: "Saturn s'ha empassat els seus fills?" — referint-se al mite del Tità Saturn que devorava la seva descendència per prevenir la profecia que el derrocaven.[5][6] Es va confondre encara més quan els anells es van tornar a veure el 1613.[4]

Els primers astrònoms van utilitzar els anagrames com una forma d'esquema de compromís per reclamar nous descobriments abans que els seus resultats estiguessin preparats per a la seva publicació. Galileu va utilitzar l'anagrama "smaismrmilmepoetaleumibunenugttauiras" per a Altissimum planetam tergeminum observavi ("He observat que el planeta més llunyà tenia una forma triple") per descobrir els anells de Saturn.[7][8][9]

El 1657 Christopher Wren es va convertir en professor d'astronomia al Gresham College de Londres. Havia estat fent observacions del planeta Saturn des de l'any 1652 amb l'objectiu d'explicar-ne l'aparició. La seva hipòtesi es va escriure a De corpore saturni, en què va estar a prop de suggerir que el planeta tenia un anell. Tanmateix, Wren no estava segur de si l'anell era independent del planeta o físicament unit a ell. Abans de la publicació de la teoria de Wren Christiaan Huygens va presentar la seva teoria dels anells de Saturn. Immediatament, Wren va reconèixer això com una hipòtesi millor que la seva i De corpore saturni mai es va publicar. Robert Hooke va ser un altre dels primers observadors dels anells de Saturn, i va notar la projecció d'ombres sobre els anells.[10]

Huygens' ring theory and later developments

[modifica]

Huygens began grinding lenses with his brother Constantijn in 1655 and was able to observe Saturn with greater detail using a 43× power refracting telescope that he designed himself. He was the first to suggest that Saturn was surrounded by a ring detached from the planet, and famously published the anagram: "Plantilla:Not a typo".[11] Three years later, he revealed it to mean Annulo cingitur, tenui, plano, nusquam coherente, ad eclipticam inclinato ("[Saturn] is surrounded by a thin, flat, ring, nowhere touching [the body of the planet], inclined to the ecliptic").[12][4][13] He published his ring theory in Systema Saturnium (1659) which also included his discovery of Saturn's moon, Titan, as well as the first clear outline of the dimensions of the Solar System.[14]

In 1675, Giovanni Domenico Cassini determined that Saturn's ring was composed of multiple smaller rings with gaps between them;[15] the largest of these gaps was later named the Cassini Division. This division is a 4,800-quilometre-wide (3,000 mi) region between the A ring and B Ring.[16]

In 1787, Pierre-Simon Laplace proved that a uniform solid ring would be unstable and suggested that the rings were composed of a large number of solid ringlets.[17][4][18]

In 1859, James Clerk Maxwell demonstrated that a nonuniform solid ring, solid ringlets or a continuous fluid ring would also not be stable, indicating that the ring must be composed of numerous small particles, all independently orbiting Saturn.[19][18] Later, Sofia Kovalevskaya also found that Saturn's rings cannot be liquid ring-shaped bodies.[20][21] Spectroscopic studies of the rings which were carried out independently in 1895 by James Keeler of the Allegheny Observatory and by Aristarkh Belopolsky of the Pulkovo Observatory showed that Maxwell's analysis was correct.[22][23]

Four robotic spacecraft have observed Saturn's rings from the vicinity of the planet. Pioneer 11's closest approach to Saturn occurred in September 1979 at a distance of 20,900 km (13,000 mi).[24] Pioneer 11 was responsible for the discovery of the F ring.[24] Voyager 1's closest approach occurred in November 1980 at a distance of 64,200 km (39,900 mi).[25] A failed photopolarimeter prevented Voyager 1 from observing Saturn's rings at the planned resolution; nevertheless, images from the spacecraft provided unprecedented detail of the ring system and revealed the existence of the G ring.[26] Voyager 2's closest approach occurred in August 1981 at a distance of 41,000 km (25,000 mi).[25] Voyager 2's working photopolarimeter allowed it to observe the ring system at higher resolution than Voyager 1, and to thereby discover many previously unseen ringlets.[27] Cassini spacecraft entered into orbit around Saturn in July 2004.[28] CassiniPlantilla:'s images of the rings are the most detailed to-date, and are responsible for the discovery of yet more ringlets.[29]

The rings are named alphabetically in the order they were discovered[30] (A and B in 1675 by Giovanni Domenico Cassini, C in 1850 by William Cranch Bond and his son George Phillips Bond, D in 1933 by Nikolai P. Barabachov and B. Semejkin, E in 1967 by Walter A. Feibelman, F in 1979 by Pioneer 11, and G in 1980 by Voyager 1). The main rings are, working outward from the planet, C, B and A, with the Cassini Division, the largest gap, separating Rings B and A. Several fainter rings were discovered more recently. The D Ring is exceedingly faint and closest to the planet. The narrow F Ring is just outside the A Ring. Beyond that are two far fainter rings named G and E. The rings show a tremendous amount of structure on all scales, some related to perturbations by Saturn's moons, but much unexplained.[30]

Inclinació axial de Saturn

[modifica]La inclinació axial de Saturn és de 26,7°, el que significa que s'obtenen vistes molt variades dels anells, dels quals els visibles ocupen el seu pla equatorial, des de la Terra en diferents moments.[31] La Terra fa passades pel pla de l'anell cada 13 o 15 anys, aproximadament cada mig any de Saturn, i hi ha aproximadament la mateixa probabilitat que es produeixin un o tres encreuaments en cada ocasió. Les travessies més recents del pla de l'anell van ser el 22 de maig de 1995, el 10 d'agost de 1995, l'11 de febrer de 1996 i el 4 de setembre de 2009; Els propers esdeveniments tindran lloc el 23 de març de 2025, el 15 d'octubre de 2038, l'1 d'abril de 2039 i el 9 de juliol de 2039. Les oportunitats favorables de visualització de travessies amb plans de l'anell (amb Saturn no a prop del Sol) només es presenten durant les travessies triples.[32][33][34]

Els equinoccis de Saturn, quan el Sol passa pel pla de l'anell, no estan uniformement espaiats; a cada òrbita, el Sol es troba al sud del pla de l'anell durant 13,7 anys terrestres, després al nord del pla durant 15,7 anys.[n 1] Les dates dels equinoccis de tardor de l'hemisferi nord inclouen el 19 de novembre de 1995 i el 6 de maig de 2025, amb els equinoccis de primavera al nord. 11 d'agost de 2009 i 23 de gener de 2039.[36] Durant el període al voltant d'un equinocci, la il·luminació de la majoria dels anells es redueix molt, fent possibles observacions úniques que destaquen característiques que s'allunyen del pla de l'anell.[37]

Physical characteristics

[modifica]

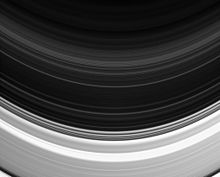

The dense main rings extend from 7,000 km (4,300 mi) to 80,000 km (50,000 mi) away from Saturn's equator, whose radius is 60,300 km (37,500 mi) (see Major subdivisions). With an estimated local thickness of as little as 10 metres (30')[38] and as much as 1 km (1000 yards),[39] they are composed of 99.9% pure water ice with a smattering of impurities that may include tholins or silicates.[40] The main rings are primarily composed of particles smaller than 10 m.[41]

Cassini directly measured the mass of the ring system via their gravitational effect during its final set of orbits that passed between the rings and the cloud tops, yielding a value of 1.54 (± 0.49) × 1019 kg, or 0.41 ± 0.13 Mimas masses.[3] This is around two-thirds the mass of the Earth's entire Antarctic ice sheet, spread across a surface area 80 times larger than that of Earth.[42][43] The estimate is close to the value of 0.40 Mimas masses derived from Cassini observations of density waves in the A, B and C rings.[3] It is a small fraction of the total mass of Saturn (about 0.25 ppb). Earlier Voyager observations of density waves in the A and B rings and an optical depth profile had yielded a mass of about 0.75 Mimas masses,[44] with later observations and computer modeling suggesting that was an underestimate.[45]

Although the largest gaps in the rings, such as the Cassini Division and Encke Gap, can be seen from Earth, the Voyager spacecraft discovered that the rings have an intricate structure of thousands of thin gaps and ringlets. This structure is thought to arise, in several different ways, from the gravitational pull of Saturn's many moons. Some gaps are cleared out by the passage of tiny moonlets such as Pan,[46] many more of which may yet be discovered, and some ringlets seem to be maintained by the gravitational effects of small shepherd satellites (similar to Prometheus and Pandora's maintenance of the F ring). Other gaps arise from resonances between the orbital period of particles in the gap and that of a more massive moon further out; Mimas maintains the Cassini Division in this manner.[47] Still more structure in the rings consists of spiral waves raised by the inner moons' periodic gravitational perturbations at less disruptive resonances. Data from the Cassini space probe indicate that the rings of Saturn possess their own atmosphere, independent of that of the planet itself. The atmosphere is composed of molecular oxygen gas (O2) produced when ultraviolet light from the Sun interacts with water ice in the rings. Chemical reactions between water molecule fragments and further ultraviolet stimulation create and eject, among other things, O2. According to models of this atmosphere, H2 is also present. The O2 and H2 atmospheres are so sparse that if the entire atmosphere were somehow condensed onto the rings, it would be about one atom thick.[48] The rings also have a similarly sparse OH (hydroxide) atmosphere. Like the O2, this atmosphere is produced by the disintegration of water molecules, though in this case the disintegration is done by energetic ions that bombard water molecules ejected by Saturn's moon Enceladus. This atmosphere, despite being extremely sparse, was detected from Earth by the Hubble Space Telescope.[49] Saturn shows complex patterns in its brightness.[50] Most of the variability is due to the changing aspect of the rings,[51][52] and this goes through two cycles every orbit. However, superimposed on this is variability due to the eccentricity of the planet's orbit that causes the planet to display brighter oppositions in the northern hemisphere than it does in the southern.[53]

In 1980, Voyager 1 made a fly-by of Saturn that showed the F ring to be composed of three narrow rings that appeared to be braided in a complex structure; it is now known that the outer two rings consist of knobs, kinks and lumps that give the illusion of braiding, with the less bright third ring lying inside them.

New images of the rings taken around the 11 August 2009 equinox of Saturn by NASA's Cassini spacecraft have shown that the rings extend significantly out of the nominal ring plane in a few places. This displacement reaches as much as 4 km (2.5 mi) at the border of the Keeler Gap, due to the out-of-plane orbit of Daphnis, the moon that creates the gap.[54]

Formation and evolution of main rings

[modifica]Estimates of the age of Saturn's rings vary widely, depending on the approach used. They have been considered to possibly be very old, dating to the formation of Saturn itself. However, data from Cassini suggest they are much younger, having most likely formed within the last 100 million years, and may thus be between 10 million and 100 million years old.[3][55] This recent origin scenario is based on a new, low mass estimate, modeling of the rings' dynamical evolution, and measurements of the flux of interplanetary dust, which feed into an estimate of the rate of ring darkening over time.[3] Since the rings are continually losing material, they would have been more massive in the past than at present.[3] The mass estimate alone is not very diagnostic, since high mass rings that formed early in the Solar System's history would have evolved by now to a mass close to that measured.[3] Based on current depletion rates, they may disappear in 300 million years.[56][57]

There are two main theories regarding the origin of Saturn's inner rings. A theory originally proposed by Édouard Roche in the 19th century, is that the rings were once a moon of Saturn (named Veritas, after a Roman goddess who hid in a well). According to the theory the moon's orbit decayed until it was close enough to be ripped apart by tidal forces (see Roche limit).[58] Numerical simulations carried out in 2022 support this theory; the authors of that study proposed the name "Chrysalis" for the destroyed moon.[59] A variation on this theory is that this moon disintegrated after being struck by a large comet or asteroid.[60] The second theory is that the rings were never part of a moon, but are instead left over from the original nebular material from which Saturn formed.

A more traditional version of the disrupted-moon theory is that the rings are composed of debris from a moon 400 to 600 km (200 to 400 miles) in diameter, slightly larger than Mimas. The last time there were collisions large enough to be likely to disrupt a moon that large was during the Late Heavy Bombardment some four billion years ago.[61]

A more recent variant of this type of theory by R. M. Canup is that the rings could represent part of the remains of the icy mantle of a much larger, Titan-sized, differentiated moon that was stripped of its outer layer as it spiraled into the planet during the formative period when Saturn was still surrounded by a gaseous nebula.[62][63] This would explain the scarcity of rocky material within the rings. The rings would initially have been much more massive (≈1,000 times) and broader than at present; material in the outer portions of the rings would have coalesced into the moons of Saturn out to Tethys, also explaining the lack of rocky material in the composition of most of these moons.[63] Subsequent collisional or cryovolcanic evolution of Enceladus might then have caused selective loss of ice from this moon, raising its density to its current value of 1.61 g/cm3, compared to values of 1.15 for Mimas and 0.97 for Tethys.[63]

The idea of massive early rings was subsequently extended to explain the formation of Saturn's moons out to Rhea.[64] If the initial massive rings contained chunks of rocky material (>100 km; 60 miles across) as well as ice, these silicate bodies would have accreted more ice and been expelled from the rings, due to gravitational interactions with the rings and tidal interaction with Saturn, into progressively wider orbits. Within the Roche limit, bodies of rocky material are dense enough to accrete additional material, whereas less-dense bodies of ice are not. Once outside the rings, the newly formed moons could have continued to evolve through random mergers. This process may explain the variation in silicate content of Saturn's moons out to Rhea, as well as the trend towards less silicate content closer to Saturn. Rhea would then be the oldest of the moons formed from the primordial rings, with moons closer to Saturn being progressively younger.[64]

The brightness and purity of the water ice in Saturn's rings have also been cited as evidence that the rings are much younger than Saturn,[55] as the infall of meteoric dust would have led to a darkening of the rings. However, new research indicates that the B Ring may be massive enough to have diluted infalling material and thus avoided substantial darkening over the age of the Solar System. Ring material may be recycled as clumps form within the rings and are then disrupted by impacts. This would explain the apparent youth of some of the material within the rings.[65] Evidence suggesting a recent origin of the C ring has been gathered by researchers analyzing data from the Cassini Titan Radar Mapper, which focused on analyzing the proportion of rocky silicates within this ring. If much of this material was contributed by a recently disrupted centaur or moon, the age of this ring could be on the order of 100 million years or less. On the other hand, if the material came primarily from micrometeoroid influx, the age would be closer to a billion years.[66]

The Cassini UVIS team, led by Larry Esposito, used stellar occultation to discover 13 objects, ranging from 27 metres (89') to 10 km (6 miles) across, within the F ring. They are translucent, suggesting they are temporary aggregates of ice boulders a few meters across. Esposito believes this to be the basic structure of the Saturnian rings, particles clumping together, then being blasted apart.[67]

Research based on rates of infall into Saturn favors a younger ring system age of hundreds of millions of years. Ring material is continually spiraling down into Saturn; the faster this infall, the shorter the lifetime of the ring system. One mechanism involves gravity pulling electrically charged water ice grains down from the rings along planetary magnetic field lines, a process termed 'ring rain'. This flow rate was inferred to be 432–2870 kg/s using ground-based Keck telescope observations; as a consequence of this process alone, the rings will be gone in ~292+818

−124 million years.[68] While traversing the gap between the rings and planet in September 2017, the Cassini spacecraft detected an equatorial flow of charge-neutral material from the rings to the planet of 4,800–44,000 kg/s.[69] Assuming this influx rate is stable, adding it to the continuous 'ring rain' process implies the rings may be gone in under 100 million years.[68][70]

Subdivisions i estructures dins dels anells

[modifica]Les parts més denses del sistema d'anells de Saturn són els anells A i B, que estan separats per la divisió de Cassini (descoberta el 1675 per Giovanni Domenico Cassini). Juntament amb l'anell C, que es va descobrir el 1850 i és de caràcter similar a la divisió de Cassini, aquestes regions constitueixen els anells principals. Els anells principals són més densos i contenen partícules més grans que els tènues anells de pols. Aquests últims inclouen l'anell D, que s'estén cap a dins fins als cims dels núvols de Saturn, els anells G i E i altres més enllà del sistema d'anells principal. Aquests anells difusos es caracteritzen com a "polsosos" a causa de la petita mida de les seves partícules (sovint al voltant d'un μm); la seva composició química és, com els anells principals, gairebé totalment gel d'aigua. L'estret anell F, just al costat de la vora exterior de l'anell A, és més difícil de categoritzar; parts són molt denses, però també conté una gran quantitat de partícules de la mida de la pols.

Paràmetres físics dels anells

[modifica]

Subdivisions principals

[modifica]| Nom[a] | Distància des del centre de Saturn (km)[b] |

Amplada(km)[b] | Gruix (m) | Anomenat en honor a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anell D | 66,900 – 74,510 | 7,500 | ||

| Anell C | 74,658 – 92,000 | 17,500 | 5 | |

| Anell B | 92,000 – 117,580 | 25,500 | 5-15 | |

| Cassini Division | 117,580 – 122,170 | 4,700 | Giovanni Cassini | |

| Anell A | 122,170 – 136,775 | 14,600 | 10-30 | |

| Divisió de Roche | 136,775 – 139,380 | 2,600 | Édouard Roche | |

| Anell F | 140,180[c] | 30 – 500 | ||

| Anell de Janus/Epimeteu[d] | 149,000 – 154,000 | 5,000 | Janus i Epimeteu | |

| Anell G | 166,000 – 175,000 | 9,000 | ||

| Arc de l'anell de Metone[d] | 194,230 | ? | Metone | |

| Arc de l'anell d'Antea[d] | 197,665 | ? | Antea | |

| Anell de Pal·lene[d] | 211,000 – 213,500 | 2,500 | Pal·lene | |

| Anell E | 180,000 – 480,000 | 300,000 | ||

| Anell de Febe | ~4,000,000 – >13,000,000 | Febe |

Estructures dels anells C

[modifica]| Nom[a] | Distància des del centre de Saturn (km)[b][c] |

Width (km)[b] | Anomenat en honor a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bretxa de Colombo | 77,870 | 150 | Giuseppe "Bepi" Colombo |

| Anell de Tità | 77,870 | 25 | Tità, satèl·lit de Saturn |

| Bretxa de Maxwell | 87,491 | 270 | James Clerk Maxwell |

| Anell de Maxwell | 87,491 | 64 | James Clerk Maxwell |

| Bretxa de Bond | 88,700 | 30 | William Cranch Bond and George Phillips Bond |

| Anell 1.470RS | 88,716 | 16 | its radius |

| Anell 1.495RS | 90,171 | 62 | its radius |

| Bretxa de Dawes | 90,210 | 20 | William Rutter Dawes |

Estructures de la divisió de Cassini

[modifica]- Font:[74]

| Nom[a] | Distància des del centre de Saturn (km)[b][c] |

Amplada (km)[b] | Anomenat en honor a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bretxa de Huygens | 117,680 | 285–400 | Christiaan Huygens |

| Anell de Huygens | 117,848 | ~17 | Christiaan Huygens |

| Bretxa de Herschel | 118,234 | 102 | William Herschel |

| Bretxa de Russell | 118,614 | 33 | Henry Norris Russell |

| Bretxa de Jeffreys | 118,950 | 38 | Harold Jeffreys |

| Bretxa de Kuiper | 119,405 | 3 | Gerard Kuiper |

| Bretxa de Laplace | 119,967 | 238 | Pierre-Simon Laplace |

| Bretxa de Bessel | 120,241 | 10 | Friedrich Bessel |

| Bretxa de Barnard | 120,312 | 13 | Edward Emerson Barnard |

structures de l'anell A

[modifica]| Nom[a] | Distància des del centre de Saturn (km)[b][c] |

Amplada (km)[b] | Anomenat en honor a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bretxa d'Encke | 133,589 | 325 | Johann Encke |

| Bretxa de Keeler | 136,505 | 35 | James Keeler |

Anell D

[modifica]

L'anell D és l'anell més interior i és molt tènue. El 1980, la Voyager 1 va detectar dins d'aquest anell tres anells designats D73, D72 i D68, sent el D68 l'anell discret més proper a Saturn. Uns 25 anys després, les imatges de la Cassini van mostrar que el D72 s'havia tornat significativament més ampli i difús, i s'havia desplaçat cap al planeta 200 km.[75]

A l'anell D hi ha una estructura a escala fina amb ones a 30 km de distància. Vista per primera vegada a la bretxa entre l'anell C i el D73,[75] l'estructura es va trobar durant l'equinocci de Saturn de 2009 per estendre's una distància radial de 19.000 km des de l'anell D fins a la vora interior de l'anell B.[76][77] Les ones s'interpreten com un patró espiral de ondulacions verticals de 2 a 20 m d'amplitud;[78] el fet que el període de les ones vagi disminuint amb el temps (de 60 km el 1995 a 30 km el 2006) permet deduir que el patró es pot haver originat a finals de 1983 amb l'impacte d'un núvol de runes (amb una massa de ≈1012 kg) d'un cometa interromput que va inclinar els anells fora del pla equatorial.[75][76][79] Un patró espiral similar a l'anell principal de Júpiter s'ha atribuït a una pertorbació causada per l'impacte del material del Cometa Shoemaker-Levy 9 el 1994.[76][80][81]

Anell C

[modifica]

L'anell C és un anell ample però tènue situat cap a dins de l'anell B. Va ser descobert el 1850 per William i George Bond, encara que William R. Dawes i Johann Galle també el van veure de manera independent. William Lassell el va anomenar "anell de Crepe" perquè semblava estar compost d'un material més fosc que els anells A i B més brillants.[82]

El seu gruix vertical s'estima en 5 metres, la seva massa al voltant d'1,1 × 1018 kg, i la seva profunditat òptica varia de 0,05 a 0,12. És a dir, entre el 5 i el 12 per cent de la llum que brilla perpendicularment a través de l'anell està bloquejada, de manera que quan es veu des de dalt, l'anell és gairebé transparent. Les ondulacions en espiral de 30 km de longitud d'ona que es van veure per primera vegada a l'anell D es van observar durant l'equinocci de Saturn de 2009 es van estendre per tot l'anell C (vegeu més amunt).

Bretxa de Colombo i anell de Tità

[modifica]La bretxa de Colombo es troba a l'anell C interior. Dins de la bretxa es troba el brillant però estret anell de Colombo, centrat a 77.883 km del centre de Saturn, que és lleugerament el·líptic en lloc de circular. Aquest anell també s'anomena anell de Tità ja que es regeix per una ressonància orbital amb el satèl·lit [[Tità (satèl·lit)|Tità.[83] En aquesta ubicació dins dels anells, la longitud de la precessió absidal d'una partícula de l'anell és igual a la longitud del moviment orbital de Tità, de manera que l'extrem exterior d'aquest anell excèntric sempre apunta cap a Tità.[83]

Bretxa i anell de Maxwell

[modifica]La bretxa de Maxwell es troba a la part exterior de l'anell C. També conté un anell dens no circular, l'anell de Maxwell. En molts aspectes, aquest anell és similar a l'ε anell d'Urà. Al centre dels dos anells hi ha estructures semblants a ones. Tot i que es creu que l'ona a l'anell ε és causada pel satèl·lit d'Urà Cordèlia, no s'ha descobert cap satèl·lit a la bretxa de Maxwell al juliol de 2008.[84]

Anell B

[modifica]L'anell B és el més gran, més brillant i més massiu dels anells. El seu gruix s'estima entre 5 i 15 m i la seva profunditat òptica varia de 0,4 a més de 5,[85] el que significa que >99% de la llum que passa per algunes parts de l'anell B està bloquejada. L'anell B conté una gran variació en la seva densitat i brillantor, gairebé tot sense explicació. Aquests són concèntrics, apareixen com a estrets anells, tot i que l'anell B no conté cap buit. En alguns llocs, la vora exterior de l'anell B conté estructures verticals que es desvien fins a 2,5 km del pla de l'anell principal, una desviació significativa del gruix vertical dels anells principals A, B i C, que generalment només és d'uns aproximadament 10 metres. Les estructures verticals es poden crear mitjançant satèl·lits incrustats invisibles.ref name=peaks>«The Tallest Peaks» (en anglès). NASA Solar System Exploration. [Consulta: 17 juliol 2023]. ![]() Aquest article incorpora text d'aquesta font, la qual és de domini públic.</ref>

Aquest article incorpora text d'aquesta font, la qual és de domini públic.</ref>

Un estudi de 2016 d'ones de densitat espiral que empra ocultacions estel·lars va indicar que la densitat superficial de l'anell B es troba en el rang de 40 a 140 g/cm2, inferior al que es creia anteriorment, i que la profunditat òptica de l'anell té poca correlació amb la seva densitat de massa (a troballa prèviament informada per als anells A i C).[85][86] Es va estimar que la massa total de l'anell B es trobava en el rang de 7 a 24×1018 kg. Això es compara amb una massa per a Mimas de 37,5×1018 kg.[85]

Radis

[modifica]Until 1980, the structure of the rings of Saturn was explained as being caused exclusively by the action of gravitational forces. Then images from the Voyager spacecraft showed radial features in the B Ring, known as spokes,[88][89] which could not be explained in this manner, as their persistence and rotation around the rings was not consistent with gravitational orbital mechanics.[90] The spokes appear dark in backscattered light, and bright in forward-scattered light (see images in Gallery); the transition occurs at a phase angle near 60°. The leading theory regarding the spokes' composition is that they consist of microscopic dust particles suspended away from the main ring by electrostatic repulsion, as they rotate almost synchronously with the magnetosphere of Saturn. The precise mechanism generating the spokes is still unknown, although it has been suggested that the electrical disturbances might be caused by either lightning bolts in Saturn's atmosphere or micrometeoroid impacts on the rings.[90]

The spokes were not observed again until some twenty-five years later, this time by the Cassini space probe. The spokes were not visible when Cassini arrived at Saturn in early 2004. Some scientists speculated that the spokes would not be visible again until 2007, based on models attempting to describe their formation. Nevertheless, the Cassini imaging team kept looking for spokes in images of the rings, and they were next seen in images taken on 5 September 2005.[91]

The spokes appear to be a seasonal phenomenon, disappearing in the Saturnian midwinter and midsummer and reappearing as Saturn comes closer to equinox. Suggestions that the spokes may be a seasonal effect, varying with Saturn's 29.7-year orbit, were supported by their gradual reappearance in the later years of the Cassini mission.[92]

Satèl·lits petits

[modifica]In 2009, during equinox, a moonlet embedded in the B ring was discovered from the shadow it cast. It is estimated to be 400 m (1,300 ft) in diameter.[93] The moonlet was given the provisional designation S/2009 S 1.

Divisió de Cassini

[modifica]

La divisió de Cassini és una regió de 4.800 km d'amplada entre l'anell A i l'anell B de Saturn. Va ser descobert l'any 1675 per Giovanni Cassini a l'Observatori de París emprant un telescopi refractor que tenia una lent objectiu de 2,5 polzades amb una distància focal de 20 peus de llarg i un augment de 90x.[94][95] Des de la Terra apareix com una fina bretxa negra en els anells. No obstant això, la Voyager va descobrir que el buit està poblat per material de l'anell molt semblant a l'anell C.[84] La divisió pot semblar brillant a les vistes del costat no il·luminat dels anells, ja que la relativament baixa densitat del material permet que es transmeti més llum a través del gruix dels anells (vegeu la segona imatge a la galeria).

La vora interior de la divisió Cassini està regida per una forta ressonància orbital. Les partícules d'anell en aquest lloc orbiten dues vegades per cada òrbita del satèl·lit Mimas.[96] La ressonància fa que les traccions de Mimas sobre aquestes partícules d'anell s'acumulin, desestabilitzant les seves òrbites i donant lloc a un tall pronunciat de la densitat de l'anell. No obstant això, moltes de les altres llacunes entre els anells dins de la divisió Cassini no s'expliquen.[97]

Bretxa de Huygens

[modifica]La bretxa de Huygens es troba a la vora interior de la divisió Cassini. Conté el dens i excèntric anell de Huygens al mig. Aquest anell presenta variacions azimutals irregulars d'amplada geomètrica i profunditat òptica, que poden ser causades per la propera ressonància 2:1 ambMimas i la influència de la vora exterior excèntrica de l'anell B. Hi ha un anell estret addicional als afores de l'anell de Huygens.[84]

A Ring

[modifica]

The A Ring is the outermost of the large, bright rings. Its inner boundary is the Cassini Division and its sharp outer boundary is close to the orbit of the small moon Atlas. The A Ring is interrupted at a location 22% of the ring width from its outer edge by the Encke Gap. A narrower gap 2% of the ring width from the outer edge is called the Keeler Gap.

The thickness of the A Ring is estimated to be 10 to 30 m, its surface density from 35 to 40 g/cm2 and its total mass as 4 to 5×1018 kg[85] (just under the mass of Hyperion). Its optical depth varies from 0.4 to 0.9.[85]

Similarly to the B Ring, the A Ring's outer edge is maintained by orbital resonances, albeit in this case a more complicated set. It is primarily acted on by the 7:6 resonance with Janus and Epimetheus, with other contributions from the 5:3 resonance with Mimas and various resonances with Prometheus and Pandora.[98][99] Other orbital resonances also excite many spiral density waves in the A Ring (and, to a lesser extent, other rings as well), which account for most of its structure. These waves are described by the same physics that describes the spiral arms of galaxies. Spiral bending waves, also present in the A Ring and also described by the same theory, are vertical corrugations in the ring rather than compression waves.[100]

In April 2014, NASA scientists reported observing the possible formative stage of a new moon near the outer edge of the A Ring.[101][102]

Encke Gap

[modifica]The Encke Gap is a 325-km (200 mile) wide gap within the A ring, centered at a distance of 133,590 km (83,000 miles) from Saturn's center.[103] It is caused by the presence of the small moon Pan,[104] which orbits within it. Images from the Cassini probe have shown that there are at least three thin, knotted ringlets within the gap.[84] Spiral density waves visible on both sides of it are induced by resonances with nearby moons exterior to the rings, while Pan induces an additional set of spiraling wakes (see image in gallery).[84]

Johann Encke himself did not observe this gap; it was named in honour of his ring observations. The gap itself was discovered by James Edward Keeler in 1888.[82] The second major gap in the A ring, discovered by Voyager, was named the Keeler Gap in his honor.[105]

The Encke Gap is a gap because it is entirely within the A Ring. There was some ambiguity between the terms gap and division until the IAU clarified the definitions in 2008; before that, the separation was sometimes called the "Encke Division".[106]

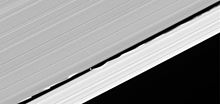

Bretxa de Keeler

[modifica]

La bretxa de Keeler és un buit de 42 km d'amplada a l'anell A, a uns 250 km de la vora exterior de l'anell. el petit satèl·lit Dafnis, descobert l'1 de maig de 2005, orbita dins d'ella, mantenint-la clara.[107] El pas del satèl·lit indueix ones a les vores de la bretxa (això també està influenciat per la seva lleugera excentricitat orbital).[84] Com que l'òrbita de Dafnis està lleugerament inclinada respecte al pla de l'anell, les ones tenen una component que és perpendicular al pla de l'anell, arribant a una distància de 1500 m "sobre" el pla.[108][109]

La bretxa de Keeler va ser descoberta per la Voyager, i batejada en honor a l'astrònom James Edward Keeler. Keeler, al seu torn, havia descobert i batejat la bretxa d'Encke en honor a Johann Encke.[82]

Satèl·lits menors d'hèlix

[modifica]

L'any 2006, es van trobar quatre petits "satèl·lits menors" a les imatges de la Cassini de l'Anell A.[110] Els satèl·lits en si mateixos només tenen uns cent metres de diàmetre, massa petits per ser vistos directament; el que veu la Cassini són les pertorbacions en forma d'"hèlix" que creen els satèl·lits, que tenen diversos km de diàmetre. S'estima que l'Anell A conté milers d'objectes d'aquest tipus. L'any 2007, el descobriment de vuit satèl·lits més va revelar que es troben en gran part confinats a un cinturó de 3.000 km, a uns 130.000 km del centre de Saturn,[111] i el 2008 s'havien detectat més de 150 satèl·lits d'hèlix.[112] Un que ha estat rastrejat durant uns quants anys ha estat batejat com Bleriot.[113]

Divisió de Roche

[modifica]

La separació entre l'anell A i l'anell F ha rebut el nom de Divisió Roche en honor al físic francès [Édouard Roche]].[114] La divisió Roche no s'ha de confondre amb el límit de Roche que és la distància a la qual un objecte gran està tan a prop d'un planeta (com Saturn) que les forces de marea del planeta el separaran.[115] Situada a la vora exterior del sistema d'anells principal, la divisió de Roche és de fet a prop del límit de Roche de Saturn, motiu pel qual els anells no s'han pogut acumular en un satèl·lit.[116]

Igual que la divisió Cassini, la divisió Roche no està buida sinó que conté una capa de material. El caràcter d'aquest material és semblant als tènues i polsegosos anells D, E i G. Dos llocs de la divisió Roche tenen una concentració de pols més elevada que la resta de la regió. Aquestes van ser descobertes per l'equip d'imatges de la sonda Cassini i se'ls va donar designacions temporals: R/2004 S 1, que es troba al llarg de l'òrbita del satèl·lit Atles; i R/2004 S 2, centrat a 138.900 km del centre de Saturn, cap a l'interior de l'òrbita de Prometeu.[117][118]

F Ring

[modifica]The F Ring is the outermost discrete ring of Saturn and perhaps the most active ring in the Solar System, with features changing on a timescale of hours.[119] It is located 3,000 km (2000 miles) beyond the outer edge of the A ring.[120] The ring was discovered in 1979 by the Pioneer 11 imaging team.[121] It is very thin, just a few hundred km (miles) in radial extent. While the traditional view has been that it is held together by two shepherd moons, Prometheus and Pandora, which orbit inside and outside it,[104] recent studies indicate that only Prometheus contributes to the confinement.[122][123] Numerical simulations suggest the ring was formed when Prometheus and Pandora collided with each other and were partially disrupted.[124]

More recent closeup images from the Cassini probe show that the F Ring consists of one core ring and a spiral strand around it.[125] They also show that when Prometheus encounters the ring at its apoapsis, its gravitational attraction creates kinks and knots in the F Ring as the moon 'steals' material from it, leaving a dark channel in the inner part of the ring (see video link and additional F Ring images in gallery). Since Prometheus orbits Saturn more rapidly than the material in the F ring, each new channel is carved about 3.2 degrees in front of the previous one.[119]

In 2008, further dynamism was detected, suggesting that small unseen moons orbiting within the F Ring are continually passing through its narrow core because of perturbations from Prometheus. One of the small moons was tentatively identified as S/2004 S 6.[119]

As of 2023, the clumpy structure of the ring "is thought to be caused by the presence of thousands of small parent bodies (1.0 to 0.1 km in size) that collide and produce dense strands of micrometre- to centimetre-sized particles that re-accrete over a few months onto the parent bodies in a steady-state regime."[126]

Outer rings

[modifica]

Anell de Janus/Epimeteu

[modifica]Hi ha un anell de pols tènue al voltant de la regió ocupada per les òrbites de Janus i Epimeteu, tal com revelen les imatges preses amb llum dispersa cap endavant per la sonda Cassini l'any 2006. L'anell té una extensió radial d'uns 5.000 km.[127] La seva font són partícules expulsades de les superfícies de les llunes per impactes de meteoroides, que després formen un anell difús al voltant dels seus camins orbitals.[128]

G Ring

[modifica]The G Ring (see last image in gallery) is a very thin, faint ring about halfway between the F Ring and the beginning of the E Ring, with its inner edge about 15,000 km (10,000 miles) inside the orbit of Mimas. It contains a single distinctly brighter arc near its inner edge (similar to the arcs in the rings of Neptune) that extends about one-sixth of its circumference, centered on the half-km (500 yard) diameter moonlet Aegaeon, which is held in place by a 7:6 orbital resonance with Mimas.[129][130] The arc is believed to be composed of icy particles up to a few m in diameter, with the rest of the G Ring consisting of dust released from within the arc. The radial width of the arc is about 250 km (150 miles), compared to a width of 9,000 km (6000 miles) for the G Ring as a whole.[129] The arc is thought to contain matter equivalent to a small icy moonlet about a hundred m in diameter.[129] Dust released from Aegaeon and other source bodies within the arc by micrometeoroid impacts drifts outward from the arc because of interaction with Saturn's magnetosphere (whose plasma corotates with Saturn's magnetic field, which rotates much more rapidly than the orbital motion of the G Ring). These tiny particles are steadily eroded away by further impacts and dispersed by plasma drag. Over the course of thousands of years the ring gradually loses mass,[131] which is replenished by further impacts on Aegaeon.

Arc de l'anell de Metone

[modifica]Un arc d'anell tènue, detectat per primera vegada el setembre de 2006, que cobreix una extensió longitudinal d'uns 10 graus s'associa amb el satèl·lit Metone. Es creu que el material de l'arc representa la pols expulsada de Metone per impactes de micrometeoroides. El confinament de la pols dins de l'arc és atribuïble a una ressonància de 14:15 amb Mimas (similar al mecanisme de confinament de l'arc dins de l'anell G).[132][133] Sota la influència de la mateixa ressonància, Methone libra cap endavant i cap enrere en la seva òrbita amb una amplitud de 5° de longitud.

Arc de l'anell d'Antea

[modifica]

Un arc d'anell tènue, detectat per primera vegada el juny de 2007, que cobreix una extensió longitudinal d'uns 20 graus s'associa amb el satèl·lit Antea. Es creu que el material de l'arc representa la pols despresa d'Antea per impactes de micrometeoroides. El confinament de la pols dins de l'arc és atribuïble a una ressonància de 10:11 amb Mimas. Sota la influència de la mateixa ressonància, Antea deriva cap endavant i cap enrere en la seva òrbita per 14° de longitud.[132][133]

Anell de Pal·lene

[modifica]Un dèbil anell de pols comparteix l'òrbita de Pal·lene, tal com van revelar les imatges preses amb llum dispersa cap endavant per la sonda espacial Cassini el 2006.[127] L'anell té una extensió radial d'uns 2.500 km. La seva font són partícules expulsades de la superfície de Pal·lene per impactes de meteoroides, que després formen un anell difús al voltant de la seva trajectòria orbital.[128][133]

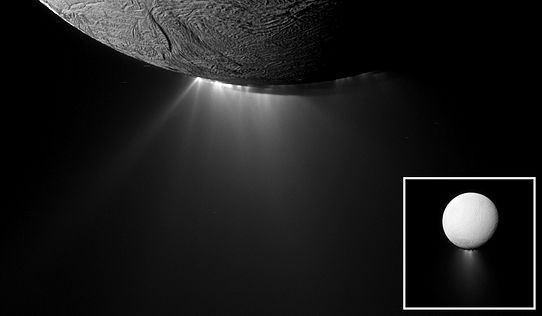

Anell E

[modifica]L'anell E és el segon anell més exterior i és extremadament ample; consisteix en moltes partícules minúscules (micròniques i submicròniques) d'aigua gelada amb silicats, diòxid de carboni i amoníac.[134] L'anell E es distribueix entre les òrbites de Mimas i Tità.[135] A diferència dels altres anells, està format per partícules microscòpiques en lloc de trossos de gel macroscòpics. L'any 2005, es va determinar que la font del material de l'anell E eren plomes criovolcàniques[136][137] que emanen de les "franges de tigre" de la regió polar sud del satèl·lit Encèlad.[138] A diferència dels anells principals, l'anell E té més de 2.000 km (1.000 milles) de gruix i augmenta amb la seva distància d'Encèlad.[135] Les estructures semblants a uns circells observats dins de l'anell E poden estar relacionades amb les emissions dels jets polars sud més actius d'Encèlad.[139]

Les partícules de l'anell E tendeixen a acumular-se als satèl3lits que orbiten al seu interior. L'equador de l'hemisferi principal de Tetis està tenyit lleugerament de blau a causa de la caiguda de material.[140]

Els satèl·lits troians Telest, Calipso, Helena i Pòl·lux es veuen especialment afectades com les seves òrbites es mouen amunt i avall pel pla de l'anell. Això fa que les seves superfícies estiguin recobertes amb un material brillant que suavitza les característiques.[141]

Els dolls polars sud del satèl·lit brollen en erupció brillant a sota.

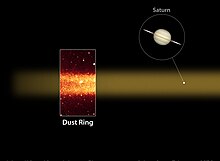

Anell de Febe

[modifica]

L'octubre de 2009 es va informar del descobriment d'un disc tènue de material just a l'interior de l'òrbita de Febe. El disc estava alineat a la vora de la Terra en el moment del descobriment. Aquest disc es pot descriure vagament com un altre anell. Encara que molt gran (tal com es veu des de la Terra, la mida aparent de dues llunes plenes [142][142]), l'anell és pràcticament invisible. Es va descobrir emprant el telescopi espacial Spitzer d'infrarojos de la NASA,[143] i es va veure en tot el rang d'observacions, que s'estenia de 128 a 207 vegades el radi de Saturn,[144] amb càlculs que indiquen que es pot estendre cap a l'exterior fins a 300 radis de Saturn i cap a dins fins a l'òrbita de Jàpet a 59 radis de Saturn.[145] L'anell es va estudiar posteriorment amb les naus WISE, Herschel i Cassini;[146] les observacions de WISE mostren que s'estén des d'almenys entre 50 i 100 fins a 270 radis de Saturn (la vora interior es perd amb la resplendor del planeta).[147] Les dades obtingudes amb WISE indiquen que les partícules de l'anell són petites; els de radi superior a 10 cm representen el 10% o menys de l'àrea de la secció transversal.[147]

Febe orbita el planeta a una distància que oscil·la entre 180 i 250 radis. L'anell té un gruix d'uns 40 radis.«The King of Rings» (en anglès). NASA, Spitzer Space Telescope center, 07-10-2009. [Consulta: 16 juliol 2023].</ref> Com que es suposa que les partícules de l'anell s'han originat per impactes (micrometeoroides i més grans) a Phoebe, haurien de compartir la seva òrbita retrògrada,[145] que és oposada al moviment orbital del següent satèl·lit interior, Jàpet. Aquest anell es troba al pla de l'òrbita de Saturn, o aproximadament l'eclíptica, i per tant està inclinat 27 graus respecte al pla equatorial de Saturn i els altres anells. Febe està inclinada a 5° respecte al pla de l'òrbita de Saturn (sovint escrit com 175°, a causa del moviment orbital retrògrad de Febe), i les seves excursions verticals resultants per sobre i per sota del pla de l'anell coincideixen estretament amb el gruix observat de l'anell de 40 radis de Saturn.

L'existència de l'anell va ser proposada als anys 70 del segle xx per Steven Soter.[145] El descobriment va ser realitzat per Anne J. Verbiscer i Michael F. Skrutskie (de la Universitat de Virgínia) i Douglas P. Hamilton (de la Universitat de Maryland, College Park).[144][148] Els tres havien estudiat junts a la Universitat de Cornell com a estudiants de postgrau.[149]

El material de l'anell migra cap a l'interior a causa de la reemissió de radiació solar,[144] amb una velocitat inversament proporcional a la mida de la partícula; una partícula de 3 cm migraria des de la proximitat de Febe a la de Jàpet al llarg de l'edat del Sistema solar.[147] Així, el material colpejaria l'hemisferi principal de Jàpet. La caiguda d'aquest material provoca un lleuger enfosquiment i envermelliment de l'hemisferi principal de Jàpet (similar al que es veu als satèl·lits d'Urà Oberó i Titània), però no crea directament la dramàtica doble coloració d'aquest satèl·lit.[150] Més aviat, el material entrant inicia una retroalimentació positiva procés d'autosegregació tèrmica de sublimació de gel de regions més càlides, seguit de condensació de vapor a regions més fredes. Això deixa un residu fosc de material "de retard" que cobreix la major part de la regió equatorial de l'hemisferi principal de Jàpet, que contrasta amb els dipòsits de gel brillant que cobreixen les regions polars i la major part de l'hemisferi posterior.[151][152][153]

Possible sistema d'anells al voltant de Rea

[modifica]S'ha plantejat la hipòtesi que Rea, el segon satèl·lit més gros de Saturn, té un sistema d'anells tènue propi que consisteix en tres bandes estretes incrustades en un disc de partícules sòlides.[154][155] Aquests anells putatius no han estat captats, però la seva existència s'ha deduït a partir de les observacions de Cassini el novembre de 2005 d'un esgotament d'electrons energètics a la magnetosfera de Saturn prop de Rea. L'Instrument d'imatge magnetosfèrica (MIMI) va observar un gradient suau marcat per tres gotes pronunciades del flux de plasma a cada costat del satèl·lit en un patró gairebé simètric. Això es podria explicar si fossin absorbits per material sòlid en forma de disc equatorial que conté anells o arcs més densos, amb partícules potser d'uns quants decímetres a aproximadament un metre de diàmetre. Una evidència més recent consistent amb la presència d'anells de Rhean és un conjunt de petits punts de llum ultraviolada distribuïts en una línia que s'estén a tres quarts de la circumferència de la lluna, a 2 graus de l'equador. Les taques s'han interpretat com els punts d'impacte del material de l'anell desorbitant.[156] Tanmateix, les observacions dirigides per la Cassini del pla d'anell putatiu des de diversos angles no han donat res, cosa que suggereix que cal una altra explicació per a aquestes característiques enigmàtiques.[157]

Galeria

[modifica]-

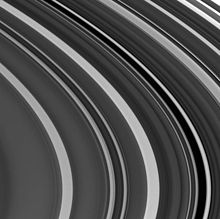

Saturn, darrere dels anells i cobert amb les seves ombres, vist per la sonda Cassini des d'una distància de 725.000 km).

-

Mosaic d'imatges de la sonda Cassini del costat no il·luminat de l'anell C exterior (inferior) i l'anell B interior (superior) prop de l'equinocci de Saturn, que mostra múltiples vistes de l'ombra de Mimas. L'ombra és atenuada per l'anell B més dens. La Divisió de Maxwell està per sota del centre.

-

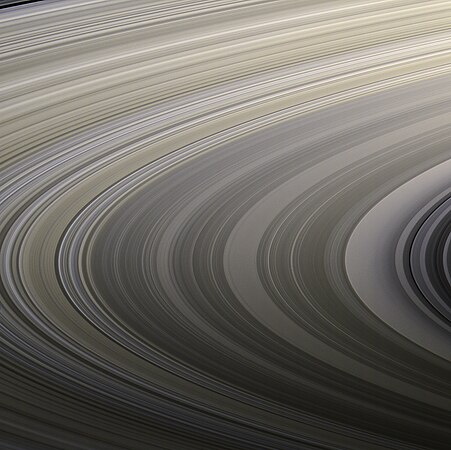

Vista en color natural de l'anell C i l'anell B exteriors.

-

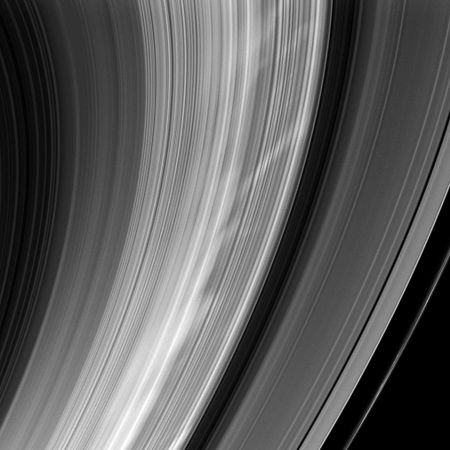

Radis de l'anell B fosc en una imatge de la Cassini d'angle de fase sota del costat no il·luminat dels anells. A l'esquerra del centre, dos buits foscos (els més grans són els Bretxa de Huygens) i els brillants (a partir d'aquesta geometria de visualització) a la seva esquerra formen la Divisió de Cassini.

-

Imatge de la Cassini del costat il·luminat pel Sol dels anells presa el 2009 amb un angle de fase de 144°, amb radis brillants de l'anell B.

-

Radially stretched (4x) view of the Keeler Gap edge waves induced by Daphnis.

-

Prometheus (at right) and Pandora orbit just inside and outside the F Ring, but only Prometheus acts as a ring shepherd.

-

F ring dynamism, probably due to perturbing effects of small moonlets orbiting close to or through the ring's core.

-

Saturn i els seus anells A, B i C en llum visible i infraroja (requadre). A la vista d'infrarojos en fals color, un major contingut de gel d'aigua i una mida de gra més gran condueixen a un color verd-blau, mentre que un major contingut sense gel i una mida de gra més petita produeixen una tonalitat vermellosa.

Notes

[modifica]- ↑ 1,0 1,1 1,2 1,3 Noms designats per la Unió Astronòmica Internacional, tret que s'indiqui el contrari. Les separacions més àmplies entre anells amb nom s'anomenen divisions, mentre que les separacions més estretes dins dels anells amb nom s'anomenen buits.

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 2,2 2,3 2,4 2,5 2,6 2,7 Dades principalment de la Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, un NASA fitxa informativa i diversos articles.[71][72][73]

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 3,2 3,3 la distància és al centre dels buits, anells i anellets que són més estrets de 1.000 km

- ↑ 4,0 4,1 4,2 4,3 unofficial name

- ↑ The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 26, 2009. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 336,000 kilometers (209,000 miles) from Saturn and at a sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 132 degrees. Image scale is 2 kilometers (1 mile) per pixel.[87]

- ↑ El radi orbital de Janus canvia lleugerament cada vegada que té una trobada propera amb el seu satèl·lit coorbital Epimeteu. Aquestes trobades condueixen a interrupcions menors periòdiques en el patró d'ona.

Referències

[modifica]- ↑ Porco, Carolyn. «Questions around Saturn's rings» (en anglès). lloc web de CICLOPS. [Consulta: 3 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 Tiscareno, M. S.; Kalas, P.; French, L. Planets, Stars and Stellar Systems (en anglès). Springer, 4 de juliol de 2012, p. 61–63. DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-5606-9_7. ISBN 978-94-007-5605-2 [Consulta: 3 juliol 2023]. «Anells planetaris»

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 3,2 3,3 3,4 3,5 3,6 Iess, L.; Militzer, B.; Kaspi, Y.; Nicholson, P.; Durante, D.; Racioppa, P.; Anabtawi, A.; Galanti, E.; Hubbard, W.; Mariani, M. J.; Tortora, P.; Wahl, S.; Zannoni, M. «Measurement and implications of Saturn's gravity field and ring mass» (en anglès). Science, 364, 6445, 2019, pàg. eaat2965. Bibcode: 2019Sci...364.2965I. DOI: 10.1126/science.aat2965. PMID: 30655447.

- ↑ 4,0 4,1 4,2 4,3 4,4 Baalke, Ron. «Historical Background of Saturn's Rings» (en anglès). Saturn Ring Plane Crossings of 1995–1996. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. [Consulta: 15 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 5,0 5,1 5,2 Whitehouse, David. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.. Renaissance Genius: Galileo Galilei and His Legacy to Modern Science (en anglès), 2009, p. [1]. ISBN 978-1-4027-6977-1. OCLC 434563173 [Consulta: 15 juliol 2023]. Error de citació: Etiqueta

<ref>no vàlida; el nom «Whitehouse2009» està definit diverses vegades amb contingut diferent. - ↑ Deiss, B. M.; Nebel, V. «On a Pretended Observation of Saturn by Galileo» (en anglès). Journal for the History of Astronomy, 29, 3, 2016, pàg. 215–220. DOI: 10.1177/002182869802900301.

- ↑ Johannes Kepler va publicar el logogrif de Galileo al prefaci de la seva Dioptrice (1611):

- Kepler, Johannes. David Frank. Dioptrice (en llatí), 1611, p. 15 del prefaci.

- Traducció anglesa: Carlos, Edward Stafford. Rivingtons. The Sidereal Messenger of Galileo Galilei and a Part of the Preface to Kepler's Dioptrics … (en anglès), 1888, p. 79–111. Vegeu les pàgines 87–88.

- Galilei, Galileo. G. Barbera. Le Opere di Galileo Galilei (en italià, llatí). 10, 1900, p. 474.

- ↑ Vegeu també:

- Partridge, E. A.; Whitaker, H. C. «Galileo's work on Saturn's rings — a historical correction» (en anglès). Popular Astronomy, 3, 1896, pàg. 408–414. Bibcode: 1896PA......3..408P.

- van Helden, Albert «Saturn and his anses» (en anglès). Journal for the History of Astronomy, 5, 2, 1974, pàg. 105–121. Bibcode: 1974JHA.....5..105V. DOI: 10.1177/002182867400500204.

- ↑ Miner, Ellis D.; Wessen, Randii R.; Cuzzi, Jeffrey N. «The scientific significance of planetary ring systems». A: Praxis. Planetary Ring Systems, 2007, p. 1–16. DOI 10.1007/978-0-387-73981-6_1. ISBN 978-0-387-34177-4.

- ↑ Alexander, A. F. O'D.. Faber and Faber Limited. The Planet Saturn (en anglès). 88, 1962, p. 108–109. DOI 10.1002/qj.49708837730. ISBN 978-0-486-23927-9.

- ↑ Borello, Petro. De Vero Telescopii Inventore … (en llatí). The Hague, Netherlands: Adriaan Vlacq, 1655, p. 62–63. Huygens' logogriph appears in the reproduction of a letter by him (De Saturni Luna (On Saturn's moon)), at the bottom of p. 63 of the Liber Secundus de Conspiciliis … [Book Two, On [early] Telescopes … ], in which the pages are numbered separately from those in the first book.

- ↑ Huygens, Christiaan. Systema Saturnium (en llatí). The Hague, Netherlands: Adriaan Vlacq, 1659, p. 47.

- ↑ Campbell, John W. Jr.. «Notes». A: Beyond the Life Line, April 1937, p. 81–85.

- ↑ Van Helden, Albert «2004ESASP1278...11V Page 11». Titan - from Discovery to Encounter, vol. 1278, 2004, pàg. 11. Bibcode: 2004ESASP1278...11V.

- ↑ Cassini «Observations nouvelles touchant le globe & l'anneau de Saturne» (en francès). Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences, vol. 10, 1677, pàg. 404–405.

- ↑ «Saturn's Cassini Division». StarChild. [Consulta: 6 juliol 2007].

- ↑ La Place «Mémoire sur la théorie de l'anneau de Saturne» (en francès). Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences de Paris, 1787, pàg. 249–267.

- ↑ 18,0 18,1 «James Clerk Maxwell on the nature of Saturn's rings». JOC/EFR, March 2006. [Consulta: 8 juliol 2007].

- ↑ Maxwell, J. Clerk. On the stability of the motion of Saturn's rings. Cambridge England: Macmillan and Co., 1859. This work had been submitted, in 1856, as an entry for the Adams prize from the University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Kowalewsky, Sophie «Zusätze und Bemerkungen zu Laplace's Untersuchungen über die Gestalt der Saturnsringe» (en alemany). Astronomische Nachrichten, vol. 111, 1885, pàg. 37–46. Bibcode: 1885AN....111...37K. This work, with two others, had been submitted in 1874 to the University of Göttingen as her doctoral dissertation.

- ↑ «Kovalevsky, Sonya (or Kovalevskaya, Sofya Vasilyevna). Entry from Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography», 2013.

- ↑ Keeler, J. E. «A spectroscopic proof of the meteoric constitution of Saturn's rings». Astrophysical Journal, vol. 1, 1895, pàg. 416–427. Bibcode: 1895ApJ.....1..416K. DOI: 10.1086/140074.

- ↑ Бѣлополъский, Ар. «Изслѣдованіе смѣщенія линій въ спектҏѣ Сатурна и его кольца» (en rus). Иӡвѣстія Императорской Академіи Наукъ (Bulletin of the Imperial Academy of Science), vol. 3, 4, 1895, pàg. 379–403.

- ↑ 24,0 24,1 Dunford, Bill. «Pioneer 11 – In Depth». NASA web site. Arxivat de l'original el 2015-12-08. [Consulta: 3 desembre 2015].

- ↑ 25,0 25,1 Angrum, Andrea. «Voyager – The Interstellar Mission». JPL/NASA web site. [Consulta: 3 desembre 2015].

- ↑ Dunford, Bill. «Voyager 1 – In Depth». NASA web site. Arxivat de l'original el 2015-10-03. [Consulta: 3 desembre 2015].

- ↑ Dunford, Bill. «Voyager 2 – In Depth». NASA web site. [Consulta: 3 desembre 2015].

- ↑ Dunford, Bill. «Cassini – Key Dates». NASA web site. Arxivat de l'original el 2017-04-13. [Consulta: 3 desembre 2015].

- ↑ Piazza, Enrico. «Cassini Solstice Mission: About Saturn & Its Moons». JPL/NASA web site. [Consulta: 3 desembre 2015].

- ↑ 30,0 30,1 «Solar System Exploration: Planets: Saturn: Rings». Solar System Exploration. Arxivat de l'original el 2010-05-27.

- ↑ Williams, David R. «Saturn Fact Sheet» (en anglès). NASA, 23-12-2016. Arxivat de l'original el 17 de juliol de 2017. [Consulta: 12 octubre 2017].

- ↑ «Saturn Ring Plane Crossing 1995» (en anglès). pds.nasa.gov. NASA, 1997. Arxivat de l'original el 11 de febrer de 2020. [Consulta: 11 febrer 2020].

- ↑ «Hubble Views Saturn Ring-Plane Crossing» (en anglès). hubblesite.org. NASA, 05-06-1995. Arxivat de l'original el 11 de febrer de 2020. [Consulta: 11 febrer 2020].

- ↑ Lakdawalla, E. «Happy Saturn ring plane crossing day!» (en anglès). www.planetary.org/blogs. The Planetary Society, 04-09-2009. [Consulta: 8 juliol 2023].

- ↑ Proctor, R.A.. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green. Saturn and Its System (en anglès), 1865, p. 166. OCLC 613706938.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, E. «Oppositions, conjunctions, seasons, and ring plane crossings of the giant planets» (en anglès). planetary.org/blogs. The Planetary Society, 07-07-2016. [Consulta: 8 juliol 2023].

- ↑ «PIA11667: The Rite of Spring» (en anglès). photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA/JPL, 21-09-2009. [Consulta: 8 juliol 2023].

- ↑ Cornell University News Service. «Researchers Find Gravitational Wakes In Saturn's Rings». ScienceDaily, 10-11-2005. [Consulta: 24 desembre 2008].

- ↑ «Saturn: Rings». NASA. Arxivat de l'original el 2010-05-27.

- ↑ Nicholson, P.D. «A close look at Saturn's rings with Cassini VIMS». Icarus, vol. 193, 1, 2008, pàg. 182–212. Bibcode: 2008Icar..193..182N. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2007.08.036.

- ↑ Zebker, H.A.; Marouf, E.A.; Tyler, G.L. «Saturn's rings – Particle size distributions for thin layer model». Icarus, vol. 64, 3, 1985, pàg. 531–548. Bibcode: 1985Icar...64..531Z. DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(85)90074-0.

- ↑ «Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica». The Cryosphere p. 15-16, 31-07-2012. [Consulta: 13 maig 2023].

- ↑ Koren, M. «The Massive Mystery of Saturn's Rings» (en anglès americà). The Atlantic, 17-01-2019. [Consulta: 21 gener 2019].

- ↑ Esposito, L. W.; O'Callaghan, M.; West, R. A. «The structure of Saturn's rings: Implications from the Voyager stellar occultation». Icarus, vol. 56, 3, 1983, pàg. 439–452. Bibcode: 1983Icar...56..439E. DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(83)90165-3.

- ↑ Stewart, Glen R.; Robbins, S. J.; Colwell, J. E. «Evidence for a Primordial Origin of Saturn's Rings». Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, vol. 39, October 2007, pàg. 420. Bibcode: 2007DPS....39.0706S.

- ↑ «Dusty Rings and Circumplanetary Dust: Observations and Simple Physics». A: Grun, E.. Interplanetary Dust. Springer, 2001, p. 641–725. ISBN 978-3-540-42067-5.

- ↑ Goldreich, Peter; Tremaine, Scott «The formation of the Cassini division in Saturn's rings». Icarus, vol. 34, 2, 1978, pàg. 240–253. Bibcode: 1978Icar...34..240G. DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(78)90165-3.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul «Saturn rings have own atmosphere». British Broadcasting Corporation, 01-07-2005.

- ↑ Johnson, R. E. «The Enceladus and OH Tori at Saturn». The Astrophysical Journal, vol. 644, 2, 2006, pàg. L137. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...644L.137J. DOI: 10.1086/505750.

- ↑ Schmude, Richard W Junior. «Wideband photoelectric magnitude measurements of Saturn in 2000». Georgia Journal of Science, 2001. [Consulta: 14 octubre 2007].

- ↑ Schmude, Richard Jr. «Wideband photometric magnitude measurements of Saturn made during the 2005–06 Apparition». Georgia Journal of Science, 22-09-2006.

- ↑ Schmude, Richard W Jr. «Saturn in 2002–03». Georgia Journal of Science, 2003. [Consulta: 14 octubre 2007].

- ↑ Henshaw, C. «Variability in Saturn». Journal of the British Astronomical Association. British Astronomical Association, vol. 113, 1, February 2003.

- ↑ «Surprising, Huge Peaks Discovered in Saturn's Rings». SPACE.com Staff. space.com, 21-09-2009. [Consulta: 26 setembre 2009].

- ↑ 55,0 55,1 Gohd, Chelsea «Saturn's rings are surprisingly young». , 17-01-2019.

- ↑ «NASA Research Reveals Saturn is Losing Its Rings at "Worst-Case-Scenario" Rate», 10 December 2018. [Consulta: 29 juny 2020].

- ↑ O'Donoghjue, James; Moore, Luke «Observations of the chemical and thermal response of 'ring rain' on Saturn's ionosphere». Icarus, vol. 322, April 2019, pàg. 251–206. Bibcode: 2019Icar..322..251O. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.10.027.

- ↑ Baalke, Ron. «Historical Background of Saturn's Rings». 1849 Roche Proposes Tidal Break-up. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Arxivat de l'original el 2009-03-21. [Consulta: 13 setembre 2008].

- ↑ Wisdom, Jack; Dbouk, Rola; Militzer, Burkhard; Hubbard, William; Nimmo, Francis; Downey, Brynna; French, Richard «Loss of a satellite could explain Saturn's obliquity and young rings». Science, vol. 377, 6612, September 15, 2022, pàg. 1285–1289. Bibcode: 2022Sci...377.1285W. DOI: 10.1126/science.abn1234. PMID: 36107998.

- ↑ «The Real Lord of the Rings». nasa.gov, 12-02-2002. Arxivat de l'original el 2010-03-23.

- ↑ Kerr, Richard A «Saturn's Rings Look Ancient Again». Science, vol. 319, 5859, 2008, pàg. 21. DOI: 10.1126/science.319.5859.21a. PMID: 18174403.

- ↑ Choi, C. Q. (2010-12-13). «Saturn's Rings Made by Giant "Lost" Moon, Study Hints». National Geographic.

- ↑ 63,0 63,1 63,2 Canup, R. M. «Origin of Saturn's rings and inner moons by mass removal from a lost Titan-sized satellite». Nature, vol. 468, 7326, 12-12-2010, pàg. 943–6. Bibcode: 2010Natur.468..943C. DOI: 10.1038/nature09661. PMID: 21151108.

- ↑ 64,0 64,1 Charnoz, S.; Crida, A.; Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; Lainey, V.; Dones, L.; Karatekin, Ö.; Tobie, G.; Mathis, S.; Le Poncin-Lafitte, C. «Accretion of Saturn's mid-sized moons during the viscous spreading of young massive rings: Solving the paradox of silicate-poor rings versus silicate-rich moons». Icarus, vol. 216, 2, December 2011, pàg. 535–550. arXiv: 1109.3360. Bibcode: 2011Icar..216..535C. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2011.09.017.

- ↑ «Saturn's Rings May Be Old Timers». NASA/JPL and University of Colorado, 12-12-2007.

- ↑ Zhang, Z.; Hayes, A.G.; Janssen, M.A.; Nicholson, P.D.; Cuzzi, J.N.; de Pater, I.; Dunn, D.E.; Estrada, P.R.; Hedman, M.M. «Cassini microwave observations provide clues to the origin of Saturn's C ring». Icarus, vol. 281, 2017, pàg. 297–321. Bibcode: 2017Icar..281..297Z. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.07.020.

- ↑ Esposito, L.W.; Albers, N.; Meinke, B.K.; Screcevic, M.; Madhusudhanan, P.; Colwell, J.E.; Jerousek, R.G. «A predator–prey model for moon-triggered clumping in Saturn's rings». Icarus, vol. 217, 1, January 2012, pàg. 103–114. Bibcode: 2012Icar..217..103E. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2011.09.029.

- ↑ 68,0 68,1 O’Donoghue, James; Moore, Luke; Connerney, Jack; Melin, Henrik; Stallard, Tom; Miller, Steve; Baines, Kevin H. «Observations of the chemical and thermal response of 'ring rain' on Saturn's ionosphere». Icarus, vol. 322, November 2018, pàg. 251–260. Bibcode: 2019Icar..322..251O. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.10.027.

- ↑ Waite, J. H.; Perryman, R. S.; Perry, M. E.; Miller, K. E.; Bell, J.; Cravens, T. E.; Glein, C. R.; Grimes, J.; Hedman, M. «Chemical interactions between Saturn's atmosphere and its rings». Science, vol. 362, 6410, 05-10-2018, pàg. eaat2382. Bibcode: 2018Sci...362.2382W. DOI: 10.1126/science.aat2382. PMID: 30287634.

- ↑ «Saturn is Officially Losing its Rings and Shockingly at Much Faster Rate than Expected». Sci-Tech Universe. [Consulta: 28 desembre 2018].

- ↑ Porco, C.; Nicholson, P. D.; Borderies, N.; Danielson, G. E.; Goldreich, P.; Holberg, J. B.; Lane, A. L. «The Eccentric Saturnian Ringlets at 1.29RS and 1.45RS» (en anglès). Icarus, 60, 1, octubre 1984, pàg. 1–16. Bibcode: 1984Icar...60....1P. DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(84)90134-9.

- ↑ Porco, C. C.; Nicholson, P. D. «Eccentric features in Saturn's outer C ring» (en anglès). Icarus, 72, 2, novembre 1987, pàg. 437–467. Bibcode: 1987Icar...72..437P. DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(87)90185-0.

- ↑ Flynn, B. C.; Cuzzi, J. N. «Regular Structure in the Inner Cassini Division of Saturn's Rings» (en anglès). Icarus, 82, 1, novembre 1989, pàg. 180–199. Bibcode: 1989Icar...82..180F. DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(89)90030-4 [Consulta: 17 juliol 2023].

- ↑ Lakdawalla. «New names for gaps in the Cassini Division within Saturn's rings» (en anglès). Planetary Society blog. Planetary Society, 09-02-2009. [Consulta: 17 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 75,0 75,1 75,2 Hedman, Matthew M.; Burns, Joseph A; Showalter, Mark R. «Saturn's dynamic D ring» (en anglès). Icarus, 188, 1, 2007, pàg. 89–107. Bibcode: 2007Icar..188...89H. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2006.11.017 [Consulta: 20 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 76,0 76,1 76,2 Mason, J.; Cook, J.-R. C. «Forensic sleuthing ties ring ripples to impacts» (en anglès). CICLOPS press release. Cassini Imaging Central Laboratory for Operations, 31-03-2011. [Consulta: 20 juliol 2023].

- ↑ «Extensive spiral corrugations» (en anglès). PIA 11664 caption. NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory / Space Science Institute, 31-03-2011. [Consulta: 30 juliol 2023].

- ↑ «Tilting Saturn's rings» (en anglès). PIA 12820 caption. NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory / Space Science Institute, 31-03-2011. [Consulta: 20 juliol 2023].

- ↑ Hedman, M. M.; Burns, J. A.; Evans, M. W.; Tiscareno, M. S.; Porco, C. C. «Saturn's curiously corrugated C Ring» (en anglès). Science, 332, 6030, 31-03-2011, pàg. 708–11. Bibcode: 2011Sci...332..708H. DOI: 10.1126/science.1202238. PMID: 21454753.

- ↑ Plantilla:Ref- web

- ↑ Showalter, M. R.; Hedman, M. M.; Burns, J. A. «The impact of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 sends ripples through the rings of Jupiter» (en anglès). Science, 332, 6030, 31-03-2011, pàg. 711–3. Arxivat de l'original el 12 de febrer de 2020. Bibcode: 2011Sci...332..711S. DOI: 10.1126/science.1202241. PMID: 21454755.

- ↑ 82,0 82,1 82,2 Harland, David M. Chichester: Praxis Publishing. Mission to Saturn: Cassini and the Huygens Probe (en anglès). Springer Science & Business Media, 20 de setembre de 2002 [Consulta: 15 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 83,0 83,1 Porco, C.; Nicholson, P. D.; Borderies, N.; Danielson, G. E.; Goldreich, P.; Holdberg, J. B.; Lane, A. L. «The eccentric Saturnian ringlets at 1.29Rs and 1.45Rs» (en anglès). Icarus, 60, 1, octubre 1984, pàg. 1–16. Bibcode: 1984Icar...60....1P. DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(84)90134-9.

- ↑ 84,0 84,1 84,2 84,3 84,4 84,5 Porco, C.C.; Baker, E.; Barbara, J.; Beurle, K; Brahic, A; Burns, JA; Charnoz, S; Cooper, N; Dawson, DD «Cassini Imaging Science: Initial Results on Saturn'sRings and Small Satellites» (en anglès). Science, 307, 5713, 2005, pàg. 1226–1236. Bibcode: 2005Sci...307.1226P. DOI: 10.1126/science.1108056. PMID: 15731439 [Consulta: 15 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 85,0 85,1 85,2 85,3 85,4 Hedman, M.M.; Nicholson, P.D. «The B-ring's surface mass density from hidden density waves: Less than meets the eye?» (en anglès). Icarus, 279, 22-01-2016, pàg. 109–124. arXiv: 1601.07955. Bibcode: 2016Icar..279..109H. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.01.007.

- ↑ Dyches, Preston. «Saturn's Rings: Less than Meets the Eye?» (en anglès). NASA, 02-02-2016. [Consulta: 17 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 87,0 87,1 Error de citació: Etiqueta

<ref>no vàlida; no s'ha proporcionat text per les refs nomenadespeaks - ↑ Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L.; Batson, R.; Bridges, P.; Inge, J.; Masursky, H.; Shoemaker, E.; Beebe, R.; Boyce, J. «A New Look at the Saturn System: The Voyager 2 Images». Science, vol. 215, 4532, 1982, pàg. 504–537. Bibcode: 1982Sci...215..504S. DOI: 10.1126/science.215.4532.504. PMID: 17771273.

- ↑ «The Alphabet Soup of Saturn's Rings». The Planetary Society, 2007. Arxivat de l'original el 2010-12-13. [Consulta: 24 juliol 2007].

- ↑ 90,0 90,1 Hamilton, Calvin. «Saturn's Magnificent Rings», 2004. [Consulta: 25 juliol 2007].

- ↑ Malik, Tarig. «Cassini Probe Spies Spokes in Saturn's Rings». Imaginova Corp., 15-09-2005. [Consulta: 6 juliol 2007].

- ↑ Mitchell, C.J.; Horanyi, M.; Havnes, O.; Porco, C.C. «Saturn's Spokes: Lost and Found». Science, vol. 311, 5767, 2006, pàg. 1587–9. Bibcode: 2006Sci...311.1587M. DOI: 10.1126/science.1123783. PMID: 16543455.

- ↑ «Cassini Solstice Mission: A Small Find Near Equinox». Cassini Solstice Mission. Arxivat de l'original el 2009-10-10. [Consulta: 16 novembre 2009].

- ↑ Webb, Thomas William. Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes (en anglès), 1859, p. 130 [Consulta: 15 juliol 2023].

- ↑ Collins, Archie Frederick. Universitat de Michigan. The greatest eye in the world: astronomical telescopes and their stories (en anglès), 1942, p. 8.

- ↑ «Lecture 41: Planetary Rings» (en anglès). ohio-state.edu.

- ↑ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. «Giovanni Cassini - Biography». Maths History. School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St. Andrews, Escòcia, 2003. [Consulta: 15 juliol 2023].

- ↑ El Moutamid, Maryame; Nicholson, Philip D.; French, Richard G.; Tiscareno, Matthew S.; Murray, Carl D.; Evans, Michael W.; French, Colleen McGhee; Hedman, Matthew M.; Burns, Joseph A. «How Janus' Orbital Swap Affects the Edge of Saturn's A Ring?». , vol. 279, 01-10-2015, pàg. 125–140. arXiv: 1510.00434. Bibcode: 2016Icar..279..125E. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2015.10.025.

- ↑ The radial density profile of Saturn's A ring.

- ↑ «Two Kinds of Wave». NASA Solar System Exploration. [Consulta: 30 maig 2019].

- ↑ Platt, Jane; Brown, Dwayne. «NASA Cassini Images May Reveal Birth of a Saturn Moon». NASA, 14-04-2014.

- ↑ Murray, C. D.; Cooper, N. J.; Williams, G. A.; Attree, N. O.; Boyer, J. S. «The discovery and dynamical evolution of an object at the outer edge of Saturn's a ring». Icarus, vol. 236, 28-03-2014, pàg. 165–168. Bibcode: 2014Icar..236..165M. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2014.03.024.

- ↑ Williams, David R. «Saturnian Rings Fact Sheet». NASA. [Consulta: 22 juliol 2008].

- ↑ 104,0 104,1 Esposito, L. W. «Planetary rings». Reports on Progress in Physics, vol. 65, 12, 2002, pàg. 1741–1783. Bibcode: 2002RPPh...65.1741E. DOI: 10.1088/0034-4885/65/12/201.

- ↑ Osterbrock, D. E.; Cruikshank, D. P. «J.E. Keeler's discovery of a gap in the outer part of the a ring». Icarus, vol. 53, 2, 1983, pàg. 165. Bibcode: 1983Icar...53..165O. DOI: 10.1016/0019-1035(83)90139-2.

- ↑ Blue, J. «Encke Division Changed to Encke Gap». USGS Astrogeology Science Center. USGS, 06-02-2008. [Consulta: 2 setembre 2010].

- ↑ Porco, C.C.; Thomas, P.C.; Weiss, J.W.; Richardson, D.C. «Saturn's Small Inner Satellites: Clues to Their Origins» (en anglès). Science, 318, 5856, 2007, pàg. 1602–1607. Bibcode: 2007Sci...318.1602P. DOI: 10.1126/science.1143977. PMID: 18063794.

- ↑ Error en el títol o la url.Mason, Joe. «» (en anglès). Lloc web CICLOPS, 11-06-2009. [Consulta: 20 juliol 2023].

- ↑ Weiss, J. W.; Porco, C. C.; Tiscareno, M. S. «Ring Edge Waves and the Masses of Nearby Satellites» (en anglès). The Astronomical Journal, 138, 1, 11-06-2009, pàg. 272–286. Bibcode: 2009AJ....138..272W. DOI: 10.1088/0004-6256/138/1/272.

- ↑ Tiscareno, Matthew S.; Burns, Joseph A.; Hedman, Matthew M.; Porco, Carolyn C.; Weiss, John W.; Dones, Luke; Richardson, Derek C.; Murray, Carl D. «100-m-diameter moonlets in Saturn's A ring from observations of 'propeller' structures» (en anglès). Nature, 440, 7084, 2006, pàg. 648–650. Bibcode: 2006Natur.440..648T. DOI: 10.1038/nature04581. PMID: 16572165.

- ↑ Sremčević, Miodrag; Schmidt, Jürgen; Salo, Heikki; Seiß, Martin; Spahn, Frank; Albers, Nicole «A belt of moonlets in Saturn's A ring» (en anglès). Nature, 449, 7165, 2007, pàg. 1019–1021. Bibcode: 2007Natur.449.1019S. DOI: 10.1038/nature06224. PMID: 17960236.

- ↑ Tiscareno, Matthew S.; Burns, Joseph A.; Hedman, Matthew M.; c. Porco, Carolyn «The population of propellers in Saturn's A Ring» (en anglès). Astronomical Journal, 135, 3, 2008, pàg. 1083–1091. arXiv: 0710.4547. Bibcode: 2008AJ....135.1083T. DOI: 10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/1083.

- ↑ Porco, C. «Bleriot Recaptured» (en anglès). Lloc web de CICLOPS. NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute, 25-02-2013. [Consulta: 23 juliol 2023].

- ↑ «Planetary Names: Ring and Ring Gap Nomenclature» (en anglès). usgs.gov.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. «Eric Weisstein's World of Physics – Roche Limit» (en anglès). scienceworld.wolfram.com, 2007. [Consulta: 15 juliol 2023].

- ↑ NASA. «What is the Roche limit?» (en anglès). NASA–JPL. [Consulta: 15 juliol 2023].

- ↑ «IAUC 8401: S/2004 S 3, S/2004 S 4,, R/2004 S 1; 2004eg, 2004eh,, 2004ei» (en anglès). www.cbat.eps.harvard.edu.

- ↑ Error en el títol o la url.«» (en anglès). www.cbat.eps.harvard.edu.

- ↑ 119,0 119,1 119,2 Murray, C. D.; Beurle, K.; Cooper, N. J.; Evans, M. W.; Williams, G. A.; Charnoz, S. «The determination of the structure of Saturn's F ring by nearby moonlets». Nature, vol. 453, 7196, June 5, 2008, pàg. 739–744. Bibcode: 2008Natur.453..739M. DOI: 10.1038/nature06999. PMID: 18528389.

- ↑ Karttunen, H.. Fundamental Astronomy. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2007. ISBN 978-3-540-34144-4. OCLC 804078150.

- ↑ Gehrels, T.; Baker, L. R.; Beshore, E.; Blenman, C.; Burke, J. J.; Castillo, N. D.; Dacosta, B.; Degewij, J.; Doose, L. R. «Imaging Photopolarimeter on Pioneer Saturn». Science, vol. 207, 4429, 1980, pàg. 434–439. Bibcode: 1980Sci...207..434G. DOI: 10.1126/science.207.4429.434. PMID: 17833555.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, E. «On the masses and motions of mini-moons: Pandora's not a "shepherd," but Prometheus still is». Planetary Society, 05-07-2014. [Consulta: 17 abril 2015].

- ↑ Cuzzi, J. N.; Whizin, A. D.; Hogan, R. C.; Dobrovolskis, A. R.; Dones, L.; Showalter, M. R.; Colwell, J. E.; Scargle, J. D. «Saturn's F Ring core: Calm in the midst of chaos». Icarus, vol. 232, April 2014, pàg. 157–175. Bibcode: 2014Icar..232..157C. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2013.12.027. ISSN: 0019-1035.

- ↑ Hyodo, R.; Ohtsuki, K. «Saturn's F ring and shepherd satellites a natural outcome of satellite system formation». Nature Geoscience, vol. 8, 9, 17-08-2015, pàg. 686–689. Bibcode: 2015NatGe...8..686H. DOI: 10.1038/ngeo2508.

- ↑ Charnoz, S.; Porco, C.C .; Deau, E.; Brahic, A; Spitale, JN; Bacques, G; Baillie, K «Cassini Discovers a Kinematic Spiral Ring Around Saturn». Science, vol. 310, 5752, 2005, pàg. 1300–1304. Bibcode: 2005Sci...310.1300C. DOI: 10.1126/science.1119387. PMID: 16311328.

- ↑ Plantilla:Cite Q

- ↑ 127,0 127,1 «PIA08328: Moon-Made Rings» (en anglès). NASA Planetary Photojournal, 11-10-2006. [Consulta: 18 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 128,0 128,1 «NASA Finds Saturn's Moons May Be Creating New Rings» (en anglès). Cassini Legacy 1997–2007. Jet Propulsion Lab, 11-10-2006. [Consulta: 18 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 129,0 129,1 129,2 Hedman, M. M.; Burns, J. A.; Tiscareno, M. S.; Porco, C. C.; Jones, G. H.; Roussos, E.; Krupp, N.; Paranicas, C.; Kempf, S. «The Source of Saturn's G Ring». Science, vol. 317, 5838, 2007, pàg. 653–656. Bibcode: 2007Sci...317..653H. DOI: 10.1126/science.1143964. PMID: 17673659.

- ↑ «S/2008 S 1. (NASA Cassini Saturn Mission Images)». ciclops.org. [Consulta: 22 setembre 2022].

- ↑ Davison, Anna «Saturn ring created by remains of long-dead moon». NewScientist.com news service, 02-08-2007.

- ↑ 132,0 132,1 Carolyn Porco|Porco, Carolyn]]. «More Ring Arcs for Saturn» (en anglès). Cassini Imaging Central Laboratory for Operations web site, 05-09-2008. Arxivat de l'original el 10 d'octubre de 2008. [Consulta: 18 juliol 2023].

- ↑ 133,0 133,1 133,2 Hedman, M. M.; Murray, C. D.; Cooper, N. J.; Tiscareno, M. S.; Beurle, K.; Evans, M. W.; Burns, J. A. «Three tenuous rings/arcs for three tiny moons» (en anglès). Icarus, 199, 2, 25-11-2008, pàg. 378–386. Bibcode: 2009Icar..199..378H. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2008.11.001.