Sistema solar: diferència entre les revisions

Cap resum de modificació |

+info |

||

| Línia 233: | Línia 233: | ||

The interplanetary medium is home to at least two disc-like regions of [[cosmic dust]]. The first, the [[interplanetary dust cloud|zodiacal dust cloud]], lies in the inner Solar System and causes the [[zodiacal light]]. It was likely formed by collisions within the asteroid belt brought on by interactions with the planets.<ref>{{ref-web|any=1998 |títol=Long-term Evolution of the Zodiacal Cloud |url=http://astrobiology.arc.nasa.gov/workshops/1997/zodiac/backman/IIIc.html |consulta=2007-02-03}}</ref> The second dust cloud extends from about 10 AU to about 40 AU, and was probably created by similar collisions within the [[Kuiper belt]].<ref>{{ref-web|any=2003 |títol=ESA scientist discovers a way to shortlist stars that might have planets |obra=ESA Science and Technology |url=http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/object/index.cfm?fobjectid=29471 |consulta=2007-02-03}}</ref><ref>{{ref-publicació|cognom=Landgraf |nom=M. |coautors=Liou, J.-C.; Zook, H. A.; Grün, E. |data= maig 2002 |títol=Origins of Solar System Dust beyond Jupiter |publicació=[[The Astronomical Journal]] |volum=123 |exemplar=5 |pàgines=2857–2861 |doi=10.1086/339704 |url=http://astron.berkeley.edu/~kalas/disksite/library/ladgraf02.pdf |consulta=2007-02-09 |bibcode=2002AJ....123.2857L}}</ref> |

The interplanetary medium is home to at least two disc-like regions of [[cosmic dust]]. The first, the [[interplanetary dust cloud|zodiacal dust cloud]], lies in the inner Solar System and causes the [[zodiacal light]]. It was likely formed by collisions within the asteroid belt brought on by interactions with the planets.<ref>{{ref-web|any=1998 |títol=Long-term Evolution of the Zodiacal Cloud |url=http://astrobiology.arc.nasa.gov/workshops/1997/zodiac/backman/IIIc.html |consulta=2007-02-03}}</ref> The second dust cloud extends from about 10 AU to about 40 AU, and was probably created by similar collisions within the [[Kuiper belt]].<ref>{{ref-web|any=2003 |títol=ESA scientist discovers a way to shortlist stars that might have planets |obra=ESA Science and Technology |url=http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/object/index.cfm?fobjectid=29471 |consulta=2007-02-03}}</ref><ref>{{ref-publicació|cognom=Landgraf |nom=M. |coautors=Liou, J.-C.; Zook, H. A.; Grün, E. |data= maig 2002 |títol=Origins of Solar System Dust beyond Jupiter |publicació=[[The Astronomical Journal]] |volum=123 |exemplar=5 |pàgines=2857–2861 |doi=10.1086/339704 |url=http://astron.berkeley.edu/~kalas/disksite/library/ladgraf02.pdf |consulta=2007-02-09 |bibcode=2002AJ....123.2857L}}</ref> |

||

==Inner Solar System== |

|||

The inner Solar System is the traditional name for the region comprising the terrestrial planets and asteroids.<ref name=inner>{{cite web |title=Inner Solar System |publisher=NASA Science (Planets) |url=http://nasascience.nasa.gov/planetary-science/exploring-the-inner-solar-system |accessdate=2009-05-09}}</ref> Composed mainly of [[silicate]]s and metals, the objects of the inner Solar System are relatively close to the Sun; the radius of this entire region is shorter than the distance between the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn. |

|||

===Inner planets=== <!--This heading linked from [[Extrasolar planet]]--> |

|||

{{Main|Terrestrial planet}} |

|||

[[File:Telluric planets size comparison.jpg|thumb|upright=1.4|The inner planets. From left to right: [[Earth]], [[Mars]], [[Venus]], and [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury]] (sizes to scale, interplanetary distances not)]] |

|||

The four inner or terrestrial planets have dense, [[rock (geology)|rocky]] compositions, few or no [[natural satellite|moons]], and no [[planetary ring|ring systems]]. They are composed largely of [[Refractory (planetary science)|refractory]] minerals, such as the [[silicate]]s, which form their [[crust (geology)|crusts]] and [[mantle (geology)|mantles]], and metals such as [[iron]] and [[nickel]], which form their [[planetary core|cores]]. Three of the four inner planets (Venus, Earth and Mars) have [[atmosphere]]s substantial enough to generate [[weather]]; all have [[impact crater]]s and [[tectonics|tectonic]] surface features such as [[rift valley]]s and [[volcano]]es. The term ''inner planet'' should not be confused with ''[[inferior planet]]'', which designates those planets that are closer to the Sun than Earth is (i.e. Mercury and Venus). |

|||

====Mercury==== |

|||

: [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury]] (0.4 [[Astronomical unit|AU]] from the Sun) is the closest planet to the Sun and the smallest planet in the Solar System (0.055 Earth masses). Mercury has no natural satellites, and its only known geological features besides impact craters are lobed ridges or [[rupes]], probably produced by a period of contraction early in its history.<ref>Schenk P., Melosh H. J. (1994), ''Lobate Thrust Scarps and the Thickness of Mercury's Lithosphere'', Abstracts of the 25th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 1994LPI....25.1203S</ref> Mercury's almost negligible atmosphere consists of atoms blasted off its surface by the solar wind.<ref>{{cite web |year=2006 |author=Bill Arnett |title=Mercury |work=The Nine Planets |url=http://www.nineplanets.org/mercury.html |accessdate=2006-09-14}}</ref> Its relatively large iron core and thin mantle have not yet been adequately explained. Hypotheses include that its outer layers were stripped off by a giant impact; or, that it was prevented from fully accreting by the young Sun's energy.<ref>Benz, W., Slattery, W. L., Cameron, A. G. W. (1988), ''Collisional stripping of Mercury's mantle'', Icarus, v. 74, p. 516–528.</ref><ref>Cameron, A. G. W. (1985), ''The partial volatilization of Mercury'', Icarus, v. 64, p. 285–294.</ref> |

|||

====Venus==== |

|||

: [[Venus]] (0.7 AU from the Sun) is close in size to Earth (0.815 Earth masses) and, like Earth, has a thick silicate mantle around an iron core, a substantial atmosphere, and evidence of internal geological activity. It is much drier than Earth, and its atmosphere is ninety times as dense. Venus has no natural satellites. It is the hottest planet, with surface temperatures over 400 [[Celsius|°C]] (752°F), most likely due to the amount of [[greenhouse gas]]es in the atmosphere.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Mark Alan Bullock |title=The Stability of Climate on Venus |publisher=Southwest Research Institute |year=1997 |url=http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~bullock/Homedocs/PhDThesis.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2006-12-26 }}</ref> No definitive evidence of current geological activity has been detected on Venus, but it has no magnetic field that would prevent depletion of its substantial atmosphere, which suggests that its atmosphere is frequently replenished by volcanic eruptions.<ref>{{cite web |year=1999 |author=Paul Rincon |title=Climate Change as a Regulator of Tectonics on Venus |work=Johnson Space Center Houston, TX, Institute of Meteoritics, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM |url=http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~bullock/Homedocs/Science2_1999.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2006-11-19}}</ref> |

|||

====Earth==== |

|||

: [[Earth]] (1 AU from the Sun) is the largest and densest of the inner planets, the only one known to have current geological activity, and the only place where [[life]] is known to exist.<ref name=life>{{cite web |title=What are the characteristics of the Solar System that lead to the origins of life? |publisher=NASA Science (Big Questions) |url=http://science.nasa.gov/planetary-science/big-questions/what-are-the-characteristics-of-the-solar-system-that-lead-to-the-origins-of-life-1/ |accessdate=2011-08-30}}</ref> Its liquid [[hydrosphere]] is unique among the terrestrial planets, and it is the only planet where [[plate tectonics]] has been observed. Earth's atmosphere is radically different from those of the other planets, having been altered by the presence of life to contain 21% free [[oxygen]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Earth's Atmosphere: Composition and Structure |author=Anne E. Egger, M.A./M.S. |work=VisionLearning.com |url=http://www.visionlearning.com/library/module_viewer.php?c3=&mid=107&l=|accessdate=2006-12-26}}</ref> It has one natural satellite, the [[Moon]], the only large satellite of a terrestrial planet in the Solar System. |

|||

====Mars==== |

|||

: [[Mars]] (1.5 AU from the Sun) is smaller than Earth and Venus (0.107 Earth masses). It possesses an atmosphere of mostly [[carbon dioxide]] with a surface pressure of 6.1 millibars (roughly 0.6% of that of Earth).<ref>{{cite book|title= Encyclopaedia of the Solar System|editor=Lucy-Ann McFadden et al.|chapter=Mars Atmosphere: History and Surface Interactions|author=David C. Gatling, Conway Leovy|pages=301–314|year=2007}}</ref> Its surface, peppered with vast volcanoes such as [[Olympus Mons]] and rift valleys such as [[Valles Marineris]], shows geological activity that may have persisted until as recently as 2 million years ago.<ref>{{cite web |year=2004 |title=Modern Martian Marvels: Volcanoes? |author=David Noever |work=NASA Astrobiology Magazine |url=http://www.astrobio.net/news/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=1360&mode=thread&order=0&thold=0 |accessdate=2006-07-23}}</ref> Its red colour comes from [[iron(III) oxide|iron oxide]] (rust) in its soil.<ref>{{cite web|title=Mars: A Kid's Eye View|publisher=NASA|url=http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/profile.cfm?Object=Mars&Display=Kids|accessdate=2009-05-14}}</ref> Mars has two tiny natural satellites ([[Deimos (moon)|Deimos]] and [[Phobos (moon)|Phobos]]) thought to be captured [[asteroid]]s.<ref>{{cite web |year=2004 |title=A Survey for Outer Satellites of Mars: Limits to Completeness |author=Scott S. Sheppard, David Jewitt, and Jan Kleyna |work=[[Astronomical Journal]] |url=http://www2.ess.ucla.edu/~jewitt/papers/2004/SJK2004.pdf|accessdate=2006-12-26}}</ref> |

|||

===Asteroid belt=== |

|||

{{Main|Asteroid belt}} |

|||

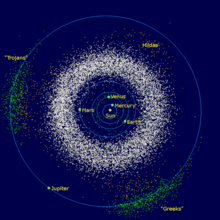

[[File:InnerSolarSystem-en.png|thumb|Image of the [[asteroid belt]] (white), the [[Jupiter trojan]]s (green), the [[Hilda family|Hildas]] (orange), and [[near-Earth object|near-Earth asteroids]].]] |

|||

[[Asteroid]]s are [[Small Solar System body|small Solar System bodies]]<ref group=lower-alpha name=footnoteB /> composed mainly of [[refractory (astronomy)|refractory]] rocky and metallic [[mineral]]s, with some ice.<ref>{{cite web|title=Are Kuiper Belt Objects asteroids? Are large Kuiper Belt Objects planets? |

|||

|publisher=[[Cornell University]]|url=http://curious.astro.cornell.edu/question.php?number=601|accessdate=2009-03-01}}</ref> |

|||

The asteroid belt occupies the orbit between Mars and Jupiter, between 2.3 and 3.3 AU from the Sun. It is thought to be remnants from the Solar System's formation that failed to coalesce because of the gravitational interference of Jupiter.<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| author=Petit, J.-M.; Morbidelli, A.; Chambers, J. |

|||

| title=The Primordial Excitation and Clearing of the Asteroid Belt |

|||

| journal=[[Icarus (journal)|Icarus]] |

|||

| year=2001 |

|||

| volume=153 |

|||

| issue=2 |

|||

| pages=338–347 |

|||

| url=http://www.gps.caltech.edu/classes/ge133/reading/asteroids.pdf |

|||

| format=PDF |

|||

| accessdate=2007-03-22 | doi = 10.1006/icar.2001.6702 |

|||

| bibcode=2001Icar..153..338P |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Asteroids range in size from hundreds of kilometres across to microscopic. All asteroids except the largest, Ceres, are classified as small Solar System bodies.<ref>{{cite web|title=IAU Planet Definition Committee|publisher=International Astronomical Union|year=2006|url=http://www.iau.org/public_press/news/release/iau0601/newspaper/|accessdate=2009-03-01}}</ref> |

|||

The asteroid belt contains tens of thousands, possibly millions, of objects over one kilometre in diameter.<ref>{{cite web |year=2002 |title=New study reveals twice as many asteroids as previously believed |work=ESA |url=http://www.esa.int/esaCP/ESAASPF18ZC_index_0.html|accessdate=2006-06-23}}</ref> Despite this, the total mass of the asteroid belt is unlikely to be more than a thousandth of that of Earth.<ref name=Krasinsky2002>{{cite journal |authorlink=Georgij A. Krasinsky |first=G. A. |last=Krasinsky |coauthors=[[Elena V. Pitjeva|Pitjeva, E. V.]]; Vasilyev, M. V.; Yagudina, E. I. |bibcode=2002Icar..158...98K |title=Hidden Mass in the Asteroid Belt |journal=[[Icarus (journal)|Icarus]] |volume=158 |issue=1 |pages=98–105 |date=July 2002 |doi=10.1006/icar.2002.6837}}</ref> The asteroid belt is very sparsely populated; [[Space probe|spacecraft]] routinely pass through without incident. Asteroids with diameters between 10 and 10<sup>−4</sup> m are called [[meteoroid]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |date=September 1995 |title=On the Definition of the Term Meteoroid |journal=[[Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society]] |volume=36 |issue=3 |pages=281–284 |bibcode=1995QJRAS..36..281B}}</ref> |

|||

====Ceres==== |

|||

[[Ceres (dwarf planet)|Ceres]] (2.77 AU) is the largest asteroid, a [[protoplanet]], and a dwarf planet.<ref group=lower-alpha name=footnoteB /> It has a diameter of slightly under 1000 km, and a mass large enough for its own gravity to pull it into a spherical shape. Ceres was considered a planet when it was discovered in 1801, and was reclassified to asteroid in the 1850s as further observations revealed additional asteroids.<ref>{{cite web |title=History and Discovery of Asteroids |format=DOC |work=NASA |url=http://dawn.jpl.nasa.gov/DawnClassrooms/1_hist_dawn/history_discovery/Development/a_modeling_scale.doc |accessdate=2006-08-29}}</ref> It was classified as a dwarf planet in 2006. |

|||

====Asteroid groups==== |

|||

Asteroids in the asteroid belt are divided into [[asteroid group]]s and [[:Category:Asteroid groups and families|families]] based on their orbital characteristics. [[Asteroid moon]]s are asteroids that orbit larger asteroids. They are not as clearly distinguished as planetary moons, sometimes being almost as large as their partners. The asteroid belt also contains [[main-belt comet]]s, which may have been the source of Earth's water.<ref>{{cite web |year=2006 |author=Phil Berardelli |title=Main-Belt Comets May Have Been Source Of Earths Water |work=SpaceDaily |url=http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Main_Belt_Comets_May_Have_Been_Source_Of_Earths_Water.html |accessdate=2006-06-23}}</ref> |

|||

[[Jupiter trojan]]s are located in either of Jupiter's [[L5 point|L<sub>4</sub> or L<sub>5</sub> points]] (gravitationally stable regions leading and trailing a planet in its orbit); the term "trojan" is also used for small bodies in any other planetary or satellite Lagrange point. [[Hilda family|Hilda asteroids]] are in a 2:3 [[Orbital resonance|resonance]] with Jupiter; that is, they go around the Sun three times for every two Jupiter orbits.<ref name=Barucci>{{cite book|last=Barucci|first=M. A.|coauthors=Kruikshank, D.P.; Mottola S.; Lazzarin M.|year=2002 |chapter=Physical Properties of Trojan and Centaur Asteroids|title=Asteroids III|publisher=University of Arizona Press|pages=273–87|location=Tucson, Arizona}}</ref> |

|||

The inner Solar System is also dusted with [[Near-Earth asteroid|rogue asteroids]], many of which cross the orbits of the inner planets.<ref name = "MorbidelliAstIII">{{cite journal|url = http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~bottke/Reprints/Morbidelli-etal_2002_AstIII_NEOs.pdf|title = Origin and Evolution of Near-Earth Objects|journal = Asteroids III|editor = W. F. Bottke Jr., A. Cellino, P. Paolicchi, and R. P. Binzel|pages = 409–422|date=January 2002|publisher = University of Arizona Press|format=PDF|bibcode = 2002aste.conf..409M}}</ref> |

|||

==Outer Solar System== |

|||

The outer region of the Solar System is home to the gas giants and their large moons. Many short-period comets, including the [[Centaur (planetoid)|centaurs]], also orbit in this region. Due to their greater distance from the Sun, the solid objects in the outer Solar System contain a higher proportion of volatiles, such as water, ammonia and methane, than the rocky denizens of the inner Solar System because the colder temperatures allow these compounds to remain solid. |

|||

===Outer planets=== |

|||

{{Main|Outer planets|Gas giant}} |

|||

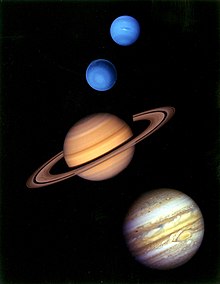

[[File:Gas giants in the solar system.jpg|thumb|From top to bottom: [[Neptune]], [[Uranus]], [[Saturn]], and [[Jupiter]] (Montage with approximate colour and size)]] |

|||

The four outer planets, or gas giants (sometimes called Jovian planets), collectively make up 99% of the mass known to orbit the Sun.<ref group=lower-alpha name=footnoteD /> Jupiter and Saturn are each many tens of times the mass of Earth and consist overwhelmingly of hydrogen and helium; Uranus and Neptune are far less massive (<20 Earth masses) and possess more ices in their makeup. For these reasons, some astronomers suggest they belong in their own category, "ice giants".<ref>{{cite web |title=Formation of Giant Planets |author=Jack J. Lissauer, David J. Stevenson |work=NASA Ames Research Center; California Institute of Technology |year=2006 |url=http://www.gps.caltech.edu/uploads/File/People/djs/lissauer&stevenson(PPV).pdf|format=PDF |accessdate=2006-01-16}}</ref> All four gas giants have [[Planetary ring|rings]], although only Saturn's ring system is easily observed from Earth. The term ''[[superior planet]]'' designates planets outside Earth's orbit and thus includes both the outer planets and Mars. |

|||

====Jupiter==== |

|||

: [[Jupiter]] (5.2 AU), at 318 Earth masses, is 2.5 times the mass of all the other planets put together. It is composed largely of [[hydrogen]] and [[helium]]. Jupiter's strong internal heat creates semi-permanent features in its atmosphere, such as cloud bands and the [[Great Red Spot]]. |

|||

: Jupiter has [[Moons of Jupiter|67 known satellites]]. The four largest, [[Ganymede (moon)|Ganymede]], [[Callisto (moon)|Callisto]], [[Io (moon)|Io]], and [[Europa (moon)|Europa]], show similarities to the terrestrial planets, such as volcanism and internal heating.<ref>{{cite web |title=Geology of the Icy Galilean Satellites: A Framework for Compositional Studies |author=Pappalardo, R T |work=Brown University |year=1999 |url=http://www.agu.org/cgi-bin/SFgate/SFgate?&listenv=table&multiple=1&range=1&directget=1&application=fm99&database=%2Fdata%2Fepubs%2Fwais%2Findexes%2Ffm99%2Ffm99&maxhits=200&=%22P11C-10%22 |accessdate=2006-01-16}}</ref> Ganymede, the largest satellite in the Solar System, is larger than Mercury. |

|||

====Saturn==== |

|||

: [[Saturn]] (9.5 AU), distinguished by its extensive [[Rings of Saturn|ring system]], has several similarities to Jupiter, such as its atmospheric composition and magnetosphere. Although Saturn has 60% of Jupiter's volume, it is less than a third as massive, at 95 Earth masses, making it the least dense planet in the Solar System.<ref name=universetoday>{{cite web|title=Density of Saturn|url=http://archive.is/LCrCb|work=Fraser Cain|publisher=universetoday.com|accessdate=2013-08-09}}</ref> The rings of Saturn are made up of small ice and rock particles. |

|||

: Saturn has [[Moons of Saturn|62 confirmed satellites]]; two of which, [[Titan (moon)|Titan]] and [[Enceladus (moon)|Enceladus]], show signs of geological activity, though they are largely [[Cryovolcano|made of ice]].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Kargel|first1=J. S.|title=Cryovolcanism on the icy satellites|journal=Earth, Moon, and Planets|volume=67|pages=101–113|year=1994|doi=10.1007/BF00613296|bibcode=1995EM&P...67..101K}}</ref> Titan, the second-largest moon in the Solar System, is larger than Mercury and the only satellite in the Solar System with a substantial atmosphere. |

|||

====Uranus==== |

|||

: [[Uranus]] (19.2 AU), at 14 Earth masses, is the lightest of the outer planets. Uniquely among the planets, it orbits the Sun on its side; its [[axial tilt]] is over ninety degrees to the [[ecliptic]]. It has a much colder core than the other gas giants and radiates very little heat into space.<ref>{{cite journal |title=10 Mysteries of the Solar System|journal=[[Astronomy Now]] |volume=19 |pages=65 |year=2005 |bibcode=2005AsNow..19h..65H }}</ref> |

|||

: Uranus has [[Moons of Uranus|27 known satellites]], the largest ones being [[Titania (moon)|Titania]], [[Oberon (moon)|Oberon]], [[Umbriel (moon)|Umbriel]], [[Ariel (moon)|Ariel]], and [[Miranda (moon)|Miranda]]. |

|||

====Neptune==== |

|||

: [[Neptune]] (30 AU), though slightly smaller than Uranus, is more massive (equivalent to 17 Earths) and therefore more [[Density|dense]]. It radiates more internal heat, but not as much as Jupiter or Saturn.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Post Voyager comparisons of the interiors of Uranus and Neptune |author=Podolak, M.; Reynolds, R. T.; Young, R. | year=1990|pages=1737|issue=10|volume=17|doi=10.1029/GL017i010p01737 |bibcode=1990GeoRL..17.1737P|journal=Geophysical Research Letters}}</ref> |

|||

: Neptune has [[Moons of Neptune|14 known satellites]]. The largest, [[Triton (moon)|Triton]], is geologically active, with [[geyser]]s of [[liquid nitrogen]].<ref>{{cite web |title=The Plausibility of Boiling Geysers on Triton |author=Duxbury, N. S., Brown, R. H. |work=Beacon eSpace |year=1995 |url=http://trs-new.jpl.nasa.gov/dspace/handle/2014/28034?mode=full |accessdate=2006-01-16 }}</ref> Triton is the only large satellite with a [[retrograde orbit]]. Neptune is accompanied in its orbit by several [[minor planet]]s, termed [[Neptune trojan]]s, that are in 1:1 [[Orbital resonance|resonance]] with it. |

|||

===Centaurs=== |

|||

{{Main|Centaur (minor planet)}} |

|||

The centaurs are icy comet-like bodies whose orbits have semi-major axes greater than Jupiter's (5.5 AU) and less than Neptune's (30 AU). The largest known centaur, [[10199 Chariklo]], has a diameter of about 250 km.<ref name=spitzer>{{Cite conference|title=Physical Properties of Kuiper Belt and Centaur Objects: Constraints from Spitzer Space Telescope |author=John Stansberry, Will Grundy, Mike Brown, Dale Cruikshank, John Spencer, David Trilling, Jean-Luc Margot|booktitle=The Solar System Beyond Neptune |arxiv=astro-ph/0702538|pages=161 |year=2007|bibcode=2008ssbn.book..161S}}</ref> The first centaur discovered, [[2060 Chiron]], has also been classified as comet (95P) because it develops a coma just as comets do when they approach the Sun.<ref>{{cite web |year=1995 |author=Patrick Vanouplines |title=Chiron biography |work=Vrije Universitiet Brussel |url=http://www.vub.ac.be/STER/www.astro/chibio.htm |accessdate=2006-06-23}}</ref> |

|||

==Comets== |

|||

{{Main|Comet}} |

|||

[[File:Comet c1995o1.jpg|upright|thumb|[[Comet Hale–Bopp]]]] |

|||

Comets are small Solar System bodies,<ref group=lower-alpha name=footnoteB /> typically only a few kilometres across, composed largely of volatile ices. They have highly eccentric orbits, generally a perihelion within the orbits of the inner planets and an aphelion far beyond Pluto. When a comet enters the inner Solar System, its proximity to the Sun causes its icy surface to [[sublimation (chemistry)|sublimate]] and [[ion]]ise, creating a [[coma (cometary)|coma]]: a long tail of gas and dust often visible to the naked eye. |

|||

Short-period comets have orbits lasting less than two hundred years. Long-period comets have orbits lasting thousands of years. Short-period comets are believed to originate in the Kuiper belt, whereas long-period comets, such as [[Comet Hale–Bopp|Hale–Bopp]], are believed to originate in the [[Oort cloud]]. Many comet groups, such as the [[Kreutz Sungrazers]], formed from the breakup of a single parent.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sekanina, Zdeněk |year=2001 |title=Kreutz sungrazers: the ultimate case of cometary fragmentation and disintegration? |volume=89 |journal=Publications of the Astronomical Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic |pages=78–93 |bibcode=2001PAICz..89...78S}}</ref> Some comets with [[hyperbolic trajectory|hyperbolic]] orbits may originate outside the Solar System, but determining their precise orbits is difficult.<ref name="hyperbolic">{{cite journal |last=Królikowska |first=M. |year=2001 |title=A study of the original orbits of ''hyperbolic'' comets |journal=[[Astronomy & Astrophysics]] |volume=376 |issue=1 |pages=316–324 |doi=10.1051/0004-6361:20010945 |bibcode=2001A&A...376..316K}}</ref> Old comets that have had most of their volatiles driven out by solar warming are often categorised as asteroids.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Whipple |first1=Fred L. |title=The activities of comets related to their aging and origin |journal=[[Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy]] |volume=54 |pages=1–11 |year=1992 |doi=10.1007/BF00049540 |bibcode=1992CeMDA..54....1W}}</ref> |

|||

==Trans-Neptunian region== |

|||

The area beyond Neptune, or the "[[trans-Neptunian object|trans-Neptunian region]]", is still [[Timeline of Solar System exploration|largely unexplored]]. It appears to consist overwhelmingly of small worlds (the largest having a diameter only a fifth that of Earth and a mass far smaller than that of the Moon) composed mainly of rock and ice. This region is sometimes known as the "outer Solar System", though others use that term to mean the region beyond the asteroid belt. |

|||

===Kuiper belt=== |

|||

{{Main|Kuiper belt}} |

|||

[[File:Outersolarsystem objectpositions labels comp.png|left|thumb|200px|Plot of all Kuiper belt objects known in 2007, set against the four outer planets]] |

|||

The Kuiper belt is a great ring of debris similar to the asteroid belt, but consisting mainly of objects composed primarily of ice.<ref name=physical>{{cite book|title=Encyclopedia of the Solar System|editor=Lucy-Ann McFadden et al. |chapter=Kuiper Belt Objects: Physical Studies|author=Stephen C. Tegler|pages=605–620|year=2007}}</ref> It extends between 30 and 50 AU from the Sun. Though it is estimated to contain anything from dozens to thousands of dwarf planets, it is composed mainly of small Solar System bodies. Many of the larger Kuiper belt objects, such as [[50000 Quaoar|Quaoar]], [[20000 Varuna|Varuna]], and [[90482 Orcus|Orcus]], may prove to be dwarf planets with further data. There are estimated to be over 100,000 Kuiper belt objects with a diameter greater than 50 km, but the total mass of the Kuiper belt is thought to be only a tenth or even a hundredth the mass of Earth.<ref name="Delsanti-Beyond_The_Planets">{{cite web |year=2006 |author=Audrey Delsanti and David Jewitt |title=The Solar System Beyond The Planets |work=Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii |url=http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/faculty/jewitt/papers/2006/DJ06.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2007-01-03|archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070129151907/http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/faculty/jewitt/papers/2006/DJ06.pdf |archivedate = January 29, 2007|deadurl=yes}}</ref> Many Kuiper belt objects have multiple satellites,<ref>{{cite doi | 10.1086/501524 }}</ref> and most have orbits that take them outside the plane of the ecliptic.<ref name=trojan>{{cite journal | url=http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~buie/biblio/pub047.pdf| author=Chiang ''et al.'' | title=Resonance Occupation in the Kuiper Belt: Case Examples of the 5:2 and Trojan Resonances | journal=[[The Astronomical Journal]] | volume=126 | issue=1 | pages=430–443 | year=2003 | doi=10.1086/375207 | accessdate=2009-08-15 | last2=Jordan | first2=A. B. | last3=Millis | first3=R. L. | last4=Buie | first4=M. W. | last5=Wasserman | first5=L. H. | last6=Elliot | first6=J. L. | last7=Kern | first7=S. D. | last8=Trilling | first8=D. E. | last9=Meech | first9=K. J. |displayauthors=9| bibcode=2003AJ....126..430C | first10=R. M.}}</ref> |

|||

The Kuiper belt can be roughly divided into the "[[Classical Kuiper belt object|classical]]" belt and the [[Resonant trans-Neptunian object|resonances]].<ref name=physical/> Resonances are orbits linked to that of Neptune (e.g. twice for every three Neptune orbits, or once for every two). The first resonance begins within the orbit of Neptune itself. The classical belt consists of objects having no resonance with Neptune, and extends from roughly 39.4 AU to 47.7 AU.<ref>{{cite journal |year=2005 |author=M. W. Buie, R. L. Millis, L. H. Wasserman, J. L. Elliot, S. D. Kern, K. B. Clancy, E. I. Chiang, A. B. Jordan, K. J. Meech, R. M. Wagner, D. E. Trilling |title=Procedures, Resources and Selected Results of the Deep Ecliptic Survey |journal=[[Earth, Moon, and Planets]] |volume=92 |issue=1 |pages=113 |arxiv=astro-ph/0309251 |bibcode=2003EM&P...92..113B |doi=10.1023/B:MOON.0000031930.13823.be}}</ref> Members of the classical Kuiper belt are classified as [[Classical Kuiper belt object|cubewanos]], after the first of their kind to be discovered, {{mpl|(15760) 1992 QB|1}}, and are still in near primordial, low-eccentricity orbits.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://sait.oat.ts.astro.it/MSAIS/3/PDF/20.pdf |format=PDF |title=Beyond Neptune, the new frontier of the Solar System |author=E. Dotto1, M. A. Barucci2, and M. Fulchignoni |accessdate=2006-12-26 |date=2006-08-24}}</ref> |

|||

====Pluto and Charon==== |

|||

{{TNO imagemap}} |

|||

The dwarf planet [[Pluto]] (39 AU average) is the largest known object in the Kuiper belt. When discovered in 1930, it was considered to be the ninth planet; this changed in 2006 with the adoption of a formal [[definition of planet]]. Pluto has a relatively eccentric orbit inclined 17 degrees to the ecliptic plane and ranging from 29.7 AU from the Sun at perihelion (within the orbit of Neptune) to 49.5 AU at aphelion. |

|||

[[Charon (moon)|Charon]], Pluto's largest moon, is sometimes described as part of a [[binary system (astronomy)|binary system]] with Pluto, as the two bodies orbit a [[Earth-Moon barycenter|barycentre]] of gravity above their surfaces (i.e. they appear to "orbit each other"). Beyond Charon, four much smaller moons, [[Styx (moon)|Styx]], [[Nix (moon)|Nix]], [[Kerberos (moon)|Kerberos]], and [[Hydra (moon)|Hydra]], are known to orbit within the system. |

|||

Pluto has a 3:2 [[orbital resonance|resonance]] with Neptune, meaning that Pluto orbits twice round the Sun for every three Neptunian orbits. Kuiper belt objects whose orbits share this resonance are called [[plutino]]s.<ref name="Fajans_et_al_2001">{{Cite journal |last=Fajans |first=J. |coauthors=L. Frièdland |date=October 2001 |title=Autoresonant (nonstationary) excitation of pendulums, Plutinos, plasmas, and other nonlinear oscillators |journal=[[American Journal of Physics]] |volume=69 |issue=10 |pages=1096–1102 |doi=10.1119/1.1389278 |url=http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~fajans/pub/pdffiles/AutoPendAJP.pdf|accessdate=2006-12-26}}</ref> |

|||

====Makemake and Haumea==== |

|||

[[Makemake (dwarf planet)|Makemake]] (45.79 AU average), although smaller than Pluto, is the largest known object in the [[Classical Kuiper belt object|''classical'' Kuiper belt]] (that is, it is not in a confirmed [[Resonant trans-Neptunian object|resonance]] with Neptune). Makemake is the brightest object in the Kuiper belt after Pluto. It was named and designated a dwarf planet in 2008.<ref name=name/> Its orbit is far more inclined than Pluto's, at 29°.<ref name=Buie136472>{{cite web |

|||

|author=Marc W. Buie |

|||

|date=2008-04-05 |

|||

|title=Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 136472 |

|||

|publisher=SwRI (Space Science Department) |

|||

|url=http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~buie/kbo/astrom/136472.html |

|||

|accessdate=2012-07-15 |

|||

|authorlink=Marc W. Buie}}</ref> |

|||

[[Haumea (dwarf planet)|Haumea]] (43.13 AU average) is in an orbit similar to Makemake except that it is caught in a 7:12 orbital resonance with Neptune.<ref name="brownlargest">{{cite web |

|||

| title = The largest Kuiper belt objects |

|||

| author = Michael E. Brown |

|||

| work = CalTech |

|||

| url = http://www.gps.caltech.edu/~mbrown/papers/ps/kbochap.pdf |

|||

| format = PDF |

|||

| accessdate = 2012-07-15}}</ref> It is about the same size as Makemake and has two natural satellites. A rapid, 3.9-hour rotation gives it a flattened and elongated shape. It was named and designated a dwarf planet in 2008.<ref name="iaunews">{{cite web |

|||

| title = News Release – IAU0807: IAU names fifth dwarf planet Haumea |

|||

| work = International Astronomical Union |

|||

| date = 2008-09-17 |

|||

| url = http://www.iau.org/public_press/news/release/iau0807/ |

|||

| accessdate = 2012-07-15}}</ref> |

|||

===Scattered disc=== |

|||

{{Main|Scattered disc}} |

|||

The scattered disc, which overlaps the Kuiper belt but extends much further outwards, is thought to be the source of short-period comets. Scattered disc objects are believed to have been ejected into erratic orbits by the gravitational influence of [[Formation and evolution of the Solar System#Planetary migration|Neptune's early outward migration]]. Most scattered disc objects (SDOs) have perihelia within the Kuiper belt but aphelia far beyond it (some have aphelia farther than 150 AU from the Sun). SDOs' orbits are also highly inclined to the ecliptic plane and are often almost perpendicular to it. Some astronomers consider the scattered disc to be merely another region of the Kuiper belt and describe scattered disc objects as "scattered Kuiper belt objects".<ref>{{cite web |year=2005 |author=David Jewitt |title=The 1000 km Scale KBOs |work=University of Hawaii |url=http://www2.ess.ucla.edu/~jewitt/kb/big_kbo.html |accessdate=2006-07-16}}</ref> Some astronomers also classify centaurs as inward-scattered Kuiper belt objects along with the outward-scattered residents of the scattered disc.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.minorplanetcenter.org/iau/lists/Centaurs.html |title=List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects |work=IAU: Minor Planet Center |accessdate=2007-04-02}}</ref> |

|||

====Eris==== |

|||

[[Eris (dwarf planet)|Eris]] (68 AU average) is the largest known scattered disc object, and caused a debate about what constitutes a planet, because it is 25% more massive than Pluto<ref name="Brown Schaller 2007">{{cite doi | 10.1126/science.1139415 }}</ref> and about the same diameter. It is the most massive of the known dwarf planets. It has one known moon, [[Dysnomia (moon)|Dysnomia]]. Like Pluto, its orbit is highly eccentric, with a [[perihelion]] of 38.2 AU (roughly Pluto's distance from the Sun) and an [[aphelion]] of 97.6 AU, and steeply inclined to the ecliptic plane. |

|||

==Regions més llunyanes== |

|||

The point at which the Solar System ends and interstellar space begins is not precisely defined because its outer boundaries are shaped by two separate forces: the solar wind and the Sun's gravity. The outer limit of the solar wind's influence is roughly four times Pluto's distance from the Sun; this ''[[Heliopause (astronomy)|heliopause]]'' is considered the beginning of the [[interstellar medium]].<ref name="Voyager" /> The Sun's [[Hill sphere]], the effective range of its gravitational dominance, is believed to extend up to a thousand times farther.<ref name=Littmann>{{cite book|last=Littmann|first=Mark|title=Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System|year=2004|pages=162–163|publisher=Courier Dover Publications|isbn=978-0-486-43602-9}}</ref> |

|||

===Heliopausa=== |

|||

[[File:IBEX all sky map.jpg|thumb|left|[[Energetic neutral atoms]] map of heliosheath and heliopause by [[IBEX]]. Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio.]] |

|||

<!-- [[File:NewHeliopause 558121.jpg|thumb|300px|NASA image of the heliosheath and heliopause]] --> |

|||

The heliosphere is divided into two separate regions. The solar wind travels at roughly 400 km/s until it collides with the [[interstellar wind]]; the flow of plasma in the [[interstellar medium]]. The collision occurs at the [[termination shock]], which is roughly 80–100 AU from the Sun upwind of the interstellar medium and roughly 200 AU from the Sun downwind.<ref name=fahr /> Here the wind slows dramatically, condenses, and becomes more turbulent,<ref name=fahr /> forming a great oval structure known as the [[heliosheath]]. This structure is believed to look and behave very much like a comet's tail, extending outward for a further 40 AU on the upwind side but tailing many times that distance downwind; evidence from the Cassini and [[Interstellar Boundary Explorer]] spacecraft has suggested that it is forced into a bubble shape by the constraining action of the interstellar magnetic field.<ref>{{cite web|title=Cassini's Big Sky: The View from the Center of Our Solar System|author=NASA/JPL|url=http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/features.cfm?feature=2370&msource=F20091119&tr=y&auid=5615216|year=2009|accessdate=2009-12-20}}</ref> The outer boundary of the heliosphere, the [[Heliopause (astronomy)|heliopause]], is the point at which the solar wind finally terminates and is the beginning of interstellar space.<ref name="Voyager">{{cite web |url=http://www.nasa.gov/vision/universe/solarsystem/voyager_agu.html |title=Voyager Enters Solar System's Final Frontier |work=NASA |accessdate=2007-04-02}}</ref> Both ''[[Voyager 1]]'' and ''[[Voyager 2]]'' are reported to have passed the termination shock and entered the heliosheath, at 94 and 84 AU from the Sun, respectively.<ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.1126/science.1117684 |date=September 2005 | author=Stone, E. C.; Cummings, A. C.; McDonald, F. B.; Heikkila, B. C.; Lal, N.; Webber, W. R. | title=Voyager 1 explores the termination shock region and the heliosheath beyond | volume=309 | issue=5743 | pages=2017–20 | pmid=16179468 | journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] | bibcode=2005Sci...309.2017S}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.1038/nature07022 |date=July 2008 | author=Stone, E. C.; Cummings, A. C.; McDonald, F. B.; Heikkila, B. C.; Lal, N.; Webber, W. R. | title=An asymmetric solar wind termination shock | volume=454 | issue=7200 | pages=71–4 | pmid=18596802 | journal=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] }}</ref> ''Voyager 1'' is also reported to have reached the heliopause.<ref name="NASA-20130912">{{cite web |last1=Cook |first1=Jia-Rui C. |last2=Agle |first2=D. C. |last3=Brown |first3=Dwayne |title=NASA Spacecraft Embarks on Historic Journey Into Interstellar Space |url=http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/voyager/voyager20130912.html |work=[[NASA]] |date=12 September 2013 |accessdate=12 September 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The shape and form of the outer edge of the heliosphere is likely affected by the [[fluid dynamics]] of interactions with the interstellar medium<ref name="fahr">{{cite journal |year=2000 |title=A 5-fluid hydrodynamic approach to model the Solar System-interstellar medium interaction |journal=[[Astronomy & Astrophysics]] | volume=357 | page=268 |url=http://aa.springer.de/papers/0357001/2300268.pdf | format=PDF | bibcode=2000A&A...357..268F }} See Figures 1 and 2.</ref> as well as solar magnetic fields prevailing to the south, e.g. it is bluntly shaped with the northern hemisphere extending 9 AU farther than the southern hemisphere. Beyond the heliopause, at around 230 AU, lies the [[bow shock]], a plasma "wake" left by the Sun as it travels through the [[Milky Way]].<ref>{{cite web | date=June 24, 2002 |author=P. C. Frisch (University of Chicago) |title=The Sun's Heliosphere & Heliopause | work=[[Astronomy Picture of the Day]] | url=http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap020624.html |accessdate=2006-06-23}}</ref> |

|||

Due to a lack of data, the conditions in local interstellar space are not known for certain. It is expected that [[NASA]]'s [[Voyager program|Voyager spacecraft]], as they pass the heliopause, will transmit valuable data on radiation levels and solar wind back to Earth.<ref>{{cite web | year=2007 | title=Voyager: Interstellar Mission | work=NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory | url=http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/interstellar.html |accessdate=2008-05-08}}</ref> How well the heliosphere shields the Solar System from cosmic rays is poorly understood. A NASA-funded team has developed a concept of a "Vision Mission" dedicated to sending a probe to the heliosphere.<ref>{{cite conference |title=Innovative Interstellar Explorer |author=R. L. McNutt, Jr. et al. | booktitle= Physics of the Inner Heliosheath: Voyager Observations, Theory, and Future Prospects |series=[[AIP Conference Proceedings]] |volume=858 |pages=341–347 |year=2006 |bibcode=2006AIPC..858..341M |doi=10.1063/1.2359348}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Interstellar space, and step on it! |work=New Scientist |url=http://space.newscientist.com/article/mg19325850.900-interstellar-space-and-step-on-it.html |date=2007-01-05 |accessdate=2007-02-05 | author=Anderson, Mark}}</ref> |

|||

===Objectes separats=== |

|||

{{main|Objecte separat}} |

|||

[[90377 Sedna]] (520 AU average) is a large, reddish object with a gigantic, highly elliptical orbit that takes it from about 76 AU at perihelion to 940 AU at aphelion and takes 11,400 years to complete. [[Michael E. Brown|Mike Brown]], who discovered the object in 2003, asserts that it cannot be part of the [[scattered disc]] or the Kuiper belt as its perihelion is too distant to have been affected by Neptune's migration. He and other astronomers consider it to be the first in an entirely new population, sometimes termed "distant detached objects" (DDOs), which also may include the object {{mpl-|148209|2000 CR|105}}, which has a perihelion of 45 AU, an aphelion of 415 AU, and an orbital period of 3,420 years.<ref>{{cite web |year=2004 |author=David Jewitt |title=Sedna – 2003 VB<sub>12</sub> |work=University of Hawaii |url=http://www2.ess.ucla.edu/~jewitt/kb/sedna.html|accessdate=2006-06-23}}</ref> Brown terms this population the "inner Oort cloud" because it may have formed through a similar process, although it is far closer to the Sun.<ref>{{cite web |title=Sedna |author=Mike Brown |year=2004 |url=http://www.gps.caltech.edu/~mbrown/sedna/ |work=CalTech |accessdate=2007-05-02}}</ref> Sedna is very likely a dwarf planet, though its shape has yet to be determined. The second unequivocally detached object, with a perihelion farther than Sedna's at roughly 81 AU, is {{mpl|2012 VP|113}}, discovered in 2012. Its aphelion is only half that of Sedna's, at 400–500 AU.<ref name="jpldata 2012 VP113"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|date=2013-10-30 last obs |

|||

|title=JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2012 VP113) |

|||

|url=http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=2012VP113 |

|||

|publisher=Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

|||

|accessdate=2014-03-26 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref><ref name="Physorg"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

| url=http://phys.org/news/2014-03-edge-solar.html |

|||

| title=A new object at the edge of our Solar System discovered |

|||

| work=Physorg.com |

|||

| date=26 March 2014 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

===Núvol d'Oort=== |

|||

{{Main|Oort cloud}} |

|||

[[File:Kuiper oort.jpg|thumb|250px|An artist's rendering of the Oort cloud, the Hills cloud, and the Kuiper belt (inset)]] |

|||

The Oort cloud is a hypothetical spherical cloud of up to a trillion icy objects that is believed to be the source for all long-period comets and to surround the Solar System at roughly 50,000 AU (around 1 [[light-year]] (ly)), and possibly to as far as 100,000 AU (1.87 ly). It is believed to be composed of comets that were ejected from the inner Solar System by gravitational interactions with the outer planets. Oort cloud objects move very slowly, and can be perturbed by infrequent events such as collisions, the gravitational effects of a passing star, or the [[galactic tide]], the [[tidal force]] exerted by the [[Milky Way]].<ref>{{cite web |year=2001 |author=Stern SA, Weissman PR. |title=Rapid collisional evolution of comets during the formation of the Oort cloud. |work=Space Studies Department, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado| url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11214311&dopt=Citation |accessdate=2006-11-19}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |year=2006 |author=Bill Arnett |title=The Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud |work=nineplanets.org |url=http://www.nineplanets.org/kboc.html |accessdate=2006-06-23}}</ref> |

|||

===Límits=== |

|||

{{See also|Vulcanoid asteroid|Planets beyond Neptune|Nemesis (hypothetical star)|Tyche (hypothetical planet)}} |

|||

Much of the Solar System is still unknown. The Sun's gravitational field is estimated to dominate the gravitational forces of [[List of nearest stars|surrounding stars]] out to about two light years (125,000 AU). Lower estimates for the radius of the Oort cloud, by contrast, do not place it farther than 50,000 AU.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Solar System: Third edition |author=T. Encrenaz, JP. Bibring, M. Blanc, MA. Barucci, F. Roques, PH. Zarka |publisher=Springer |year=2004 |page=1}}</ref> Despite discoveries such as Sedna, the region between the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud, an area tens of thousands of AU in radius, is still virtually unmapped. There are also ongoing studies of the region between Mercury and the Sun.<ref>{{cite journal |year=2004 |pages=312–315 |volume=148 |journal=[[Icarus (journal)|Icarus]] |author=Durda D. D.; Stern S. A.; Colwell W. B.; Parker J. W.; Levison H. F.; Hassler D. M. |title=A New Observational Search for Vulcanoids in SOHO/LASCO Coronagraph Images |doi=10.1006/icar.2000.6520 |bibcode=2000Icar..148..312D}}</ref> Objects may yet be discovered in the Solar System's uncharted regions. |

|||

In November 2012 NASA announced that as [[Voyager 1]] approached the transition zone to the outer limit of the Solar System, its instruments detected a sharp intensification of the magnetic field. No change in the direction of the magnetic field had occurred, which NASA scientists then interpreted to indicate that Voyager 1 had not yet left the Solar System.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/voyager/voyager20121203.html |title=NASA Voyager 1 Encounters New Region in Deep Space |last1=Greicius |first1=Tony |last2= |first2= |date=3 December 2012 |work= |publisher=NASA |accessdate=26 January 2013}}</ref> |

|||

==Context galàctic== |

|||

{{imageframe|width=300|caption=Position of the Solar System within the Milky Way|content= |

|||

{{Superimpose |

|||

| base = Milky Way Arms ssc2008-10.svg |

|||

| base_width = 300px |

|||

| base_alt = Position of the Solar System within the Milky Way |

|||

| base_caption = Position of the Solar System within the Milky Way |

|||

| float = Yellow Arrow Down.png |

|||

| float_width = 16px |

|||

| x = 142 |

|||

| y = 55 |

|||

}} }} |

|||

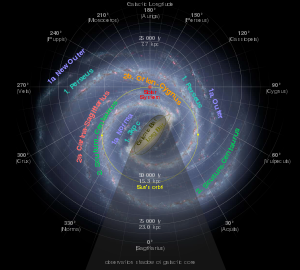

The Solar System is located in the [[Milky Way]], a [[barred spiral galaxy]] with a diameter of about 100,000 [[light-year]]s containing about 200 billion stars.<ref name="fn9"> |

|||

{{cite press |

|||

|last=English |first=J. |

|||

|title=Exposing the Stuff Between the Stars |

|||

|url = http://www.ras.ucalgary.ca/CGPS/press/aas00/pr/pr_14012000/pr_14012000map1.html |

|||

|publisher=Hubble News Desk |

|||

|year=2000 |

|||

|accessdate = 2007-05-10 |

|||

}}</ref> The Sun resides in one of the Milky Way's outer spiral arms, known as the [[Orion–Cygnus Arm]] or Local Spur.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Three Dimensional Structure of the Milky Way Disk |author=R. Drimmel, D. N. Spergel |year=2001 |pages=181–202 |volume=556 |doi=10.1086/321556 |journal=[[Astrophysical Journal]] |arxiv=astro-ph/0101259 |bibcode=2001ApJ...556..181D}}</ref> The Sun lies between 25,000 and 28,000 light years from the [[Galactic Centre]],<ref name="distance2"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|last=Eisenhauer |first=F. |

|||

|coauthors=et al. |

|||

|title=A Geometric Determination of the Distance to the Galactic Center |

|||

|journal=[[Astrophysical Journal]] |

|||

|volume=597 |issue=2 |pages=L121–L124 |

|||

|year=2003 |

|||

|doi=10.1086/380188 |

|||

|bibcode=2003ApJ...597L.121E |

|||

}}</ref> and its speed within the galaxy is about 220 [[metre per second|kilometres per second]] (140 mi/s), so that it completes one revolution every 225–250 million years. This revolution is known as the Solar System's [[galactic year]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Period of the Sun's Orbit around the Galaxy (Cosmic Year) |first=Stacy |last=Leong |url=http://hypertextbook.com/facts/2002/StacyLeong.shtml |year=2002 |work=The Physics Factbook |accessdate=2007-04-02}}</ref> The [[solar apex]], the direction of the Sun's path through interstellar space, is near the constellation [[Hercules (constellation)|Hercules]] in the direction of the current location of the bright star [[Vega]].<ref>{{cite web |year=2003 |author=C. Barbieri |title=Elementi di Astronomia e Astrofisica per il Corso di Ingegneria Aerospaziale V settimana |work=IdealStars.com |url=http://dipastro.pd.astro.it/planets/barbieri/Lezioni-AstroAstrofIng04_05-Prima-Settimana.ppt |accessdate=2007-02-12}}</ref> The plane of the ecliptic lies at an angle of about 60° to the [[galactic plane]].{{Refn|If ψ is the angle between the [[Ecliptic pole|north pole of the ecliptic]] and the north [[galactic pole]] then: |

|||

:<math>\cos\psi=\cos(\beta_g)\cos(\beta_e)\cos(\alpha_g-\alpha_e)+\sin(\beta_g)\sin(\beta_e)</math>, |

|||

where <math>\beta_g=</math>27° 07′ 42.01″ and <math>\alpha_g=</math>12h 51m 26.282 are the declination and right ascension of the north galactic pole,<ref>{{cite journal | last=Reid| first=M.J. | coauthors=Brunthaler, A. | title=The Proper Motion of Sagittarius A* | journal=[[The Astrophysical Journal]] | volume=616 | issue=2 | page=883 | doi=10.1086/424960 | month=2004 | year=2004 | bibcode=2004ApJ...616..872R}}</ref> whereas <math>\beta_e=</math>66° 33′ 38.6″ and <math>\alpha_e=</math>18h 0m 00 are those for the north pole of the ecliptic. (Both pairs of coordinates are for [[J2000]] epoch.) The result of the calculation is 60.19°.|group=lower-alpha}} |

|||

The Solar System's location in the galaxy is a factor in the [[evolution]] of [[life]] on Earth. Its orbit is close to circular, and orbits near the Sun are at roughly the same speed as that of the spiral arms. Therefore, the Sun passes through arms only rarely. Because spiral arms are home to a far larger concentration of [[supernova]]e, gravitational instabilities, and radiation that could disrupt the Solar System, this has given Earth long periods of stability for life to evolve.<ref name="astrobiology">{{cite web |year=2001 |author=Leslie Mullen |title=Galactic Habitable Zones |work=Astrobiology Magazine |url=http://www.astrobio.net/news/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=139 |accessdate=2006-06-23}}</ref> The Solar System also lies well outside the star-crowded environs of the galactic centre. Near the centre, gravitational tugs from nearby stars could perturb bodies in the [[Oort Cloud]] and send many comets into the inner Solar System, producing collisions with potentially catastrophic implications for life on [[Earth]]. The intense radiation of the galactic centre could also interfere with the development of complex life.<ref name=astrobiology/> Even at the Solar System's current location, some scientists have hypothesised that recent [[supernovae]] may have adversely affected life in the last 35,000 years by flinging pieces of expelled stellar core towards the Sun as radioactive dust grains and larger, comet-like bodies.<ref>{{cite web |year=2005 |author=|title=Supernova Explosion May Have Caused Mammoth Extinction |work=Physorg.com |url=http://www.physorg.com/news6734.html |accessdate=2007-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

===Veïnatge=== |

|||

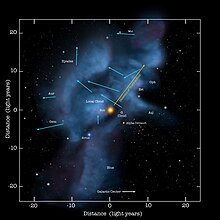

[[File:Local Interstellar Clouds with motion arrows.jpg|thumb|Beyond the heliosphere is the interstellar medium, consisting of various clouds of gases. (see [[Local Interstellar Cloud]])]] |

|||

The Solar System is currently located in the [[Local Interstellar Cloud]] or Local Fluff. It is thought to be near the neighbouring [[G-Cloud]], but it is unknown if the Solar System is embedded in the Local Interstellar Cloud, or if it is in the region where the Local Interstellar Cloud and G-Cloud are interacting.<ref>[http://interstellar.jpl.nasa.gov/interstellar/probe/introduction/neighborhood.html Our Local Galactic Neighborhood], NASA, 05-06-2013</ref><ref>[http://www.centauri-dreams.org/?p=14203 Into the Interstellar Void], Centauri Dreams, 05-06-2013</ref> The Local Interstellar Cloud is an area of denser cloud in an otherwise sparse region known as the [[Local Bubble]], an hourglass-shaped cavity in the [[interstellar medium]] roughly 300 light years across. The bubble is suffused with high-temperature plasma that suggests it is the product of several recent supernovae.<ref>{{cite web |title=Near-Earth Supernovas |work=NASA |url=http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2003/06jan_bubble.htm |accessdate=2006-07-23}}</ref> |

|||

There are relatively few [[List of nearest stars|stars within ten light years]] (95 trillion km, or 60 trillion mi) of the Sun. The closest is the triple star system [[Alpha Centauri]], which is about 4.4 light years away. Alpha Centauri A and B are a closely tied pair of Sun-like stars, whereas the small [[red dwarf]] Alpha Centauri C (also known as [[Proxima Centauri]]) orbits the pair at a distance of 0.2 light years. The stars next closest to the Sun are the red dwarfs [[Barnard's Star]] (at 5.9 light years), [[Wolf 359]] (7.8 light years), and [[Lalande 21185]] (8.3 light years). The largest star within ten light years is [[Sirius]], a bright [[main sequence|main-sequence]] star roughly twice the Sun's mass and orbited by a [[white dwarf]] called Sirius B. It lies 8.6 light years away. The remaining systems within ten light years are the binary red-dwarf system [[Luyten 726-8]] (8.7 light years) and the solitary red dwarf [[Ross 154]] (9.7 light years).<ref>{{cite web |title=Stars within 10 light years |url=http://www.solstation.com/stars/s10ly.htm|work=SolStation |accessdate=2007-04-02}}</ref> The Solar System's closest solitary Sun-like star is [[Tau Ceti]], which lies 11.9 light years away. It has roughly 80% of the Sun's mass but only 60% of its luminosity.<ref>{{cite web |title=Tau Ceti |url=http://www.solstation.com/stars/tau-ceti.htm |work=SolStation |accessdate=2007-04-02}}</ref> The closest known [[extrasolar planet]] to the Sun lies around Alpha Centauri B. Its one confirmed planet, [[Alpha Centauri Bb]], is at least 1.1 times Earth's mass and orbits its star every 3.236 days.<ref>{{cite doi | 10.1038/nature11572}}</ref> |

|||

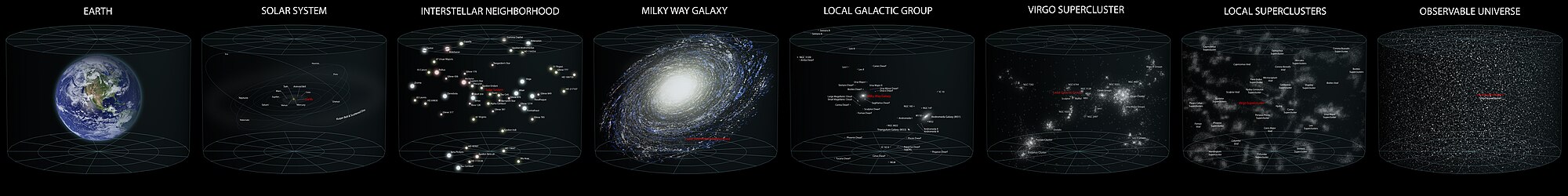

{{wide image|Earth's Location in the Universe (JPEG).jpg|2000px|A diagram of Earth's location in the [[observable Universe]]. (''[[:File:Earth's Location in the Universe SMALLER (JPEG).jpg|Click here for an alternate image]].'')}} |

|||

==Resum visual== |

|||

This section is a sampling of Solar System bodies, selected for size and quality of imagery, and sorted by volume. Some omitted objects are larger than the ones included here, notably [[Pluto]] and [[Eris (dwarf planet)|Eris]], because these have not been imaged in high quality. |

|||

{{SolarSummary}} |

|||

== Regions del sistema solar == |

== Regions del sistema solar == |

||

Revisió del 21:42, 28 març 2014

|

|

Aquest article o secció s'està elaborant i està inacabat. Un viquipedista hi està treballant i és possible que trobeu defectes de contingut o de forma. Comenteu abans els canvis majors per coordinar-los. Aquest avís és temporal: es pot treure o substituir per {{incomplet}} després d'uns dies d'inactivitat. |

Els planetes i els planetes nans del sistema solar amb mides de mostra a escala, però amb distàncies reduïdes. | |

| Edat | 4,568 bilions d'anys |

|---|---|

| Ubicació | Núvol interestel·lar local, Bombolla local, Braç d'Orió, Via Làctia |

| Massa del sistema | 1,0014 masses solars |

| Estrella més propera | Pròxima del Centaure (4,22 al), sistema d'Alfa del Centaure (4,37 al) |

| Sistema planetari més proper conegut | Sistema d'Alfa del Centaure (4,37 al) |

| Sistema planetari | |

| Semi-eix major exterior (Neptú) | 30,10 UA (4,503 bilions de km) |

| Distància al límit exterior | 50 UA |

| Nombre d'estrelles | 1 Sol |

| Nombre de planetes | 8 Mercuri, Venus, Terra, Mart, Júpiter, Saturn, Urà, Neptú |

| Nombre de planetes nans coneguts | Possiblement diversos centenars.[1] 5 (Ceres, Plutó, Haumea, Makemake i Eris) actualment estan reconeguts per la IAU |

| Nombre de satèl·lits naturals coneguts | 422 (173 de planetes[2] i 249 de planetes menors[3]) |

| Nombre de planetes menors coneguts | 628,057 (as of 2013-12-12)[4] |

| Nombre de cometes coneguts | 3.244 (fins el 2013-12-12)[4] |

| Nombre de satèl·lits rodons coneguts | 19 |

| Òrbita al voltant del centre galàctic | |

| Inclinació del pla invariable al pla galàctic | 60,19° (eclíptica) |

| Distància al Centre Galàctic | 27.000±1.000 al |

| Velocitat orbital | 220 km/s |

| Període orbital | 225–250 Ma |

| Propietats relacionades amb l'estrella | |

| Tipus espectral | G2V |

| Línia de congelament | ≈5 UA[5] |

| Distància a la heliopausa | ≈120 UA |

| Radi de l'esfera de Hill | ≈1–2 al |

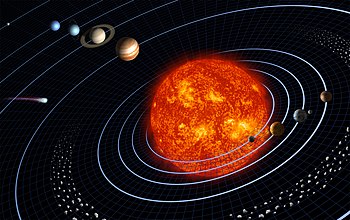

El sistema solar[a] és el Sol i els objectes que l'orbiten al voltant. Per tant, és un sistema planetari de vuit planetes[b] i diversos cossos secundaris, planetes nans i objectes menors del sistema solar que orbiten el sol directament ,[c] com també els satèl·lits (llunes) que orbiten molts planetes i objectes més petits. El sistema solar es va formar fa 4,6 bilions d'anys a partir del col·lapse gravitatori d'un núvol molecular gegant. La gran majoria de la massa del sistema és al sol, amb la major part de la massa restant continguda a Júpiter. Els quatre planetes interns més petits, Mercuri, Venus, Terra i Mart, també anomenats els planetes tel·lúrics, es componen sobretot de roca i metall. Els quatre planetes exteriors, anomenats els gegants gasosos, són substancialment més massius que els terrestres. Els dos més grans, Júpiter i Saturn, estan compostos principalment d'hidrogen i heli, els dos planetes més externs, Urà i Neptú, es componen en gran part de les substàncies amb punts de fusió relativament alts (en comparació amb l'hidrogen i l'heli), anomenats gels, com ara aigua, amoníac i metà, i es refereixen sovint per separat com a "gegants de gel". Tots els planetes tenen òrbites gairebé circulars que es troben dins d'un disc gairebé pla anomenat el pla eclíptic.

El sistema solar també conté regions poblades d'objectes més petits.[c] El cinturó d'asteroides, que es troba entre Mart i Júpiter, majoritàriament conté objectes compostos, com els planetes terrestres, de roca i metall. Més enllà de l'òrbita de Neptú, hi ha el cinturó de Kuiper i el disc dispers, vinculats amb poblacions d'objectes transneptunians compostos principalment de gel. Dins d'aquestes poblacions són diverses desenes a més de deu mil objectes que poden ser prou grans com per haver estat arrodonits per la seva pròpia gravetat.[10] Aquests objectes es denominen planetes nans. Entre els planetes nans identificats s'inclouen l'asteroide Ceres i els objectes transneptunians Plutó i Eris.[c] A més d'aquestes dues regions, existeixen altres poblacions de petits cossos incloent cometes, centaures i la pols interplanetària que viatgen lliurement entre les regions. Sis dels planetes, almenys tres dels planetes nans, i molts dels cossos més petits estan en òrbita amb satèl·lits naturals,[d] generalment denominats "llunes" de la Lluna de la Terra. Cadascun dels planetes externs és envoltat per anells planetaris de pols i altres objectes petits.

El vent solar, un flux de plasma que ve del sol, crea una bombolla en el medi interestel·lar coneguda com la helioesfera, que s'estén fins al límit del disc dispers. El núvol d'Oort, que es creu que és la font de cometes de període llarg, també poden existir en una distància prop de mil vegades més lluny que l'heliosfera. La heliopausa és el punt en què la pressió del vent solar és igual a la pressió oposada del vent interestel·lar. El sistema solar es troba situat dins d'un dels braços exteriors de la Via Làctia, que conté aproximadament 200 bilions d'estrelles.

Descobriment del sistema solar

El descobriment del sistema solar va començar en la més remota antiguitat. Totes les antigues civilitzacions tenien ja coneixement del Sol, la Lluna i els planetes, encara que llavors només se'n coneixien 5: Mercuri, Venus, Mart, Júpiter i Saturn. El nom de "planetes" els va ser donat pels antics grecs i significa "errants", ja que es desplaçaven pel firmament en trajectòries aparentment erràtiques. Es desconeix qui i quan els va observar per primera vegada. A la resta de punts brillants del firmament els anomenaven les estrelles "fixes", perquè sempre es trobaven a la mateixa posició les unes respecte de les altres. El coneixement que es creia que es tenia a l'antiguitat sobre la naturalesa de cada un d'aquests objectes era totalment incorrecte.

La Terra no es considerava planeta perquè es pensava que la Terra estava quieta al centre del món mentre tots els altres objectes del firmament, inclòs el Sol, giraven al seu voltant. Això és el que s'anomena model geocèntric del sistema solar. No obstant això, ja cap al 270 aC, el filòsof grec Aristarc de Samos va proposar que era la Terra la que girava al voltant del Sol, però la seva idea no va tenir gaire bona acollida. Uns anys més tard, Eratòstenes va calcular el diàmetre de la Terra amb força exactitud. El sistema geocèntric va ser perfeccionat per Ptolemeu cap a l'any 150 dC i des de llavors i fins al segle XVII va ser el sistema dominant a Europa.[11]

Al segle XVI, va tenir lloc el que es coneix com a Revolució Copernicana, que va tenir com a origen la publicació del llibre De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium de Nicolau Copèrnic el 1543. Copèrnic va proposar un model heliocèntric del sistema solar, on era el Sol i no la Terra el que es trobava al centre del món i tots els planetes, inclosa la Terra, giraven al seu voltant. La idea de Copèrnic va ser fortament rebutjada per l'Església Catòlica però amb el pas dels segles es va acabar imposant.[12]

L'any 1609, la invenció del telescopi va suposar un gran avanç tecnològic en el descobriment del sistema solar. Un any després, Galileo Galilei va enfocar el seu telescopi cap al cel i va descobrir quatre llunes que giraven al voltant de Júpiter. Això demostrava que no tots els cossos giren al voltant de la Terra i era un argument a favor de la teoria heliocèntrica. Entre el 1609 i el 1618, Johannes Kepler va formular les seves lleis del moviment planetari que descriuen les òrbites dels planetes al voltant del Sol. El 1687, Isaac Newton va descobrir la llei de la gravitació universal que explica la força que manté als planetes movent-se en òrbita al voltant del Sol i dona una raó de perquè els planetes es mouen tal com diuen les lleis de Kepler.

El 1781, William Herschel va descobrir un nou planeta, Urà. Era el primer planeta que es descobria des de l'antiguitat. El 1801, Giuseppe Piazzi va descobrir el primer i el més gran dels asteroides, (1) Ceres, entre les òrbites de Mart i Júpiter. En els anys següents es van descobrir molts altres asteroides, la majoria en òrbites semblants a Ceres formant el cinturó d'asteroides. El 1846, Johann Galle va descobrir Neptú, observant allà on els càlculs teòrics de Urbain Le Verrier i John Couch Adams deien que hi havia d'haver un nou planeta. Finalment, Clyde Tombaugh el 1930 va descobrir el novè planeta, Plutó.

En els últims anys, els descobriments en el sistema solar s'han centrat principalment en nous satèl·lits dels planetes gegants, nous asteroides i nous cometes. És destacable el descobriment, l'any 1992, de l'objecte (15760) 1992 QB1 més enllà de l'òrbita de Neptú, que va desencadenar el descobriment de molts altres objectes semblants, ara coneguts amb el nom d'objectes transneptunians. Aquests objectes es concentren principalment en la regió del cinturó de Kuiper. El més gran de tots ells és 2003 UB313, descobert l'any 2005. Aquest objecte és fins i tot més gran que Plutó i s'ha suggerit que podria ser el desè planeta del sistema solar.

Exploració del sistema solar

Des del començament de l'era espacial el 1957, la major part de l'exploració del sistema solar s'ha realitzat mitjançant missions espacials no tripulades, organitzades i executades per diferents agències espacials (bàsicament, l'estatunidenca NASA, el programa espacial soviètic i l'europea ESA). La primera nau espacial en posar-se sobre la superfície d'un altre cos del sistema solar va ser la sonda soviètica Luna 2 que va impactar contra la Lluna el 1959. Des de llavors, s'ha arribat a cossos cada vegada més distants, amb sondes aterrant a Venus el 1965, a Mart el 1976, a l'asteroide (433) Eros el 2001 i al satèl·lit de Saturn Tità el 2005. Fins ara, cap sonda s'ha posat sobre Mercuri però la Mariner 10 el va sobrevolar de prop el 1973.

La primera sonda a explorar els planetes exteriors va ser la Pioneer 10 que va sobrevolar Júpiter el 1973. La Pioneer 11 va ser la primera a visitar Saturn el 1979. Les sondes Voyager van realitzar un gran tour del sistema solar visitant Júpiter el 1979 i Saturn el 1980-1981. A més, la Voyager 2 va continuar el seu viatge passant a prop d'Urà el 1986 i de Neptú el 1989. Les sondes Voyager ara es troben molt més enllà de l'òrbita de Plutó i s'estan apropant a l'heliopausa que marca el límit exterior del sistema solar. Plutó és l'únic planeta que encara no ha estat visitat per cap sonda espacial. No obstant això, la sonda New Horizons, llançada el gener del 2006, està previst que arribi a Plutó cap al juliol del 2015 i després intentarà visitar algun objecte del cinturó de Kuiper encara per determinar.

A través d'aquestes missions no tripulades, s'han pogut obtenir fotografies d'alta resolució de la majoria de planetes i satèl·lits del sistema solar i d'algun asteroide i cometa també. També s'han realitzat anàlisis de les atmosferes dels cossos visitats i, en els casos de les sondes que s'han posat sobre la superfície, s'ha pogut estudiar en detall l'escorça de l'objecte. D'altra banda, l'exploració espacial tripulada només ha portat els humans fins a la Lluna, que va ser trepitjada per primera vegada pels astronautes de l'Apollo 11 el 1969. L'última missió lunar tripulada va ser la de l'Apollo 17 el 1972, però el recent descobriment d'aigua gelada en la regió del pol sud lunar ha fet augmentar les expectatives de retornar a la Lluna durant la pròxima dècada. D'altra banda, les missions tripulades a Mart han estat llargament anticipades per generacions d'entusiastes de l'espai. Actualment, l'Agència Espacial Europea, a través del Programa Aurora, i la NASA, a través de la Vision for Space Exploration, estan planejant missions tripulades a la Lluna i a Mart per a un futur no molt llunyà.

Composició i estructura del sistema solar

The principal component of the Solar System is the Sun, a G2 main-sequence star that contains 99.86% of the system's known mass and dominates it gravitationally.[13] The Sun's four largest orbiting bodies, the gas giants, account for 99% of the remaining mass, with Jupiter and Saturn together comprising more than 90%.[e]

Most large objects in orbit around the Sun lie near the plane of Earth's orbit, known as the ecliptic. The planets are very close to the ecliptic, whereas comets and Kuiper belt objects are frequently at significantly greater angles to it.[17][18] All the planets and most other objects orbit the Sun in the same direction that the Sun is rotating (counter-clockwise, as viewed from a long way above Earth's north pole).[19] There are exceptions, such as Halley's Comet.

The overall structure of the charted regions of the Solar System consists of the Sun, four relatively small inner planets surrounded by a belt of rocky asteroids, and four gas giants surrounded by the Kuiper belt of icy objects. Astronomers sometimes informally divide this structure into separate regions. The inner Solar System includes the four terrestrial planets and the asteroid belt. The outer Solar System is beyond the asteroids, including the four gas giants.[20] Since the discovery of the Kuiper belt, the outermost parts of the Solar System are considered a distinct region consisting of the objects beyond Neptune.[21]

Most of the planets in the Solar System possess secondary systems of their own, being orbited by planetary objects called natural satellites, or moons (two of which are larger than the planet Mercury), and, in the case of the four gas giants, by planetary rings, thin bands of tiny particles that orbit them in unison. Most of the largest natural satellites are in synchronous rotation, with one face permanently turned toward their parent.

Kepler's laws of planetary motion describe the orbits of objects about the Sun. Following Kepler's laws, each object travels along an ellipse with the Sun at one focus. Objects closer to the Sun (with smaller semi-major axes) travel more quickly because they are more affected by the Sun's gravity. On an elliptical orbit, a body's distance from the Sun varies over the course of its year. A body's closest approach to the Sun is called its perihelion, whereas its most distant point from the Sun is called its aphelion. The orbits of the planets are nearly circular, but many comets, asteroids, and Kuiper belt objects follow highly elliptical orbits. The positions of the bodies in the Solar System can be predicted using numerical models.

Although the Sun dominates the system by mass, it accounts for only about 2% of the angular momentum[22] due to the differential rotation within the gaseous Sun.[23] The planets, dominated by Jupiter, account for most of the rest of the angular momentum due to the combination of their mass, orbit, and distance from the Sun, with a possibly significant contribution from comets.[22]

The Sun, which comprises nearly all the matter in the Solar System, is composed of roughly 98% hydrogen and helium.[24] Jupiter and Saturn, which comprise nearly all the remaining matter, possess atmospheres composed of roughly 99% of these elements.[25][26] A composition gradient exists in the Solar System, created by heat and light pressure from the Sun; those objects closer to the Sun, which are more affected by heat and light pressure, are composed of elements with high melting points. Objects farther from the Sun are composed largely of materials with lower melting points.[27] The boundary in the Solar System beyond which those volatile substances could condense is known as the frost line, and it lies at roughly 5 AU from the Sun.[5]

The objects of the inner Solar System are composed mostly of rock,[28] the collective name for compounds with high melting points, such as silicates, iron or nickel, that remained solid under almost all conditions in the protoplanetary nebula.[29] Jupiter and Saturn are composed mainly of gases, the astronomical term for materials with extremely low melting points and high vapour pressure such as molecular hydrogen, helium, and neon, which were always in the gaseous phase in the nebula.[29] Ices, like water, methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide,[28] have melting points up to a few hundred kelvins.[29] They can be found as ices, liquids, or gases in various places in the Solar System, whereas in the nebula they were either in the solid or gaseous phase.[29] Icy substances comprise the majority of the satellites of the giant planets, as well as most of Uranus and Neptune (the so-called "ice giants") and the numerous small objects that lie beyond Neptune's orbit.[28][30] Together, gases and ices are referred to as volatiles.[31]

Cossos

En termes generals, el sistema solar està estructurat de la forma següent: al centre es troba el Sol, una estrella. Al voltant del Sol giren els 8 cossos majors, anomenats planetes, que són (ordenats del més proper al més llunyà al Sol): Mercuri, Venus, la Terra, Mart, Júpiter, Saturn, Urà i Neptú; Plutó des del 24 d'agost de 2006 ja no és considerat un planeta, sinó un planeta nan. També al voltant del Sol giren centenars de milers de cossos més petits que, segons la seva mida, composició i òrbita es classifiquen en planetes menors o planetoides, meteoroides i cometes. Els planetes menors es divideixen en dos grups: els asteroides i els objectes transneptunians, encara que a vegades quan es parla d'asteroides es fa referència a tot el conjunt de planetes menors. Els podem trobar escampats per tot el sistema solar però principalment es concentren en dues regions: el cinturó d'asteroides o cinturó principal, situat entre les òrbites de Mart i Júpiter i el cinturó de Kuiper, que es troba més enllà de l'òrbita de Neptú. Els meteoroides són petites roques de menys de 50 metres de diàmetre que estan escampades per tot el sistema solar. Els cometes són enormes blocs de gel i roca amb òrbites molt excèntriques. Es creu que podria existir una regió molt allunyada del Sol anomenada núvol d'Oort que seria la font d'on provenen els cometes.

Al voltant dels planetes giren els satèl·lits naturals o llunes. Cada planeta té un nombre diferent de satèl·lits. En total, se n'han descobert 162 i estan distribuïts així: a la Terra, 1 satèl·lit; a Mart, 2 satèl·lits; a Júpiter, 63 satèl·lits; a Saturn, 56 satèl·lits; a Urà, 27 satèl·lits; a Neptú, 13 satèl·lits i a Plutó, 3 satèl·lits. Mercuri i Venus no en tenen cap. Aquestes xifres estan contínuament subjectes a canvi a causa del descobriment de nous satèl·lits. Alguns asteroides tenen els seus propis satèl·lits naturals que s'anomenen satèl·lits asteroidals.

Òrbites

Tots els cossos del sistema solar estan lligats al Sol a través de la força de la gravetat segons la llei de la gravitació universal de Newton. El mateix passa entre els satèl·lits i els cossos als quals orbiten. La gravetat és una força atractiva la intensitat de la qual és més gran com més massa té un cos i s'afebleix a mesura que la distància entre els cossos augmenta. El Sol és, amb molta diferència, el cos amb més massa del sistema solar (un 99,86%), per això atrau a tots els altres cossos cap a ell. Al mateix temps, cada cos atrau el Sol cap a ell però aquest efecte és tan petit que el podem ignorar. Aquesta força d'atracció provoca que els cossos "caiguin" cap al Sol, però com que al mateix temps es mouen a gran velocitat en direcció perpendicular a la força d'atracció, per la 3ª llei de Newton apareix una força de reacció que s'equilibra amb la gravetat i permet als cossos mantenir-se en trajectòries més o menys estables anomenades òrbites.

Les òrbites dels cossos del sistema solar estan determinades per les lleis de Kepler, descobertes per l'astrònom alemany Johannes Kepler entre el 1609 i el 1618. Aquestes lleis són tres i diuen el següent:

- El grau d'allargament d'una el·lipse es mesura amb l'excentricitat, que val 0 si la corba és una circumferència i 1 si és una paràbola. Per a la majoria de planetes, l'excentricitat és menor que 0,1 i, per tant, les seves òrbites són pràcticament circulars. Dues excepcions són Mercuri amb 0,21 i Plutó amb 0,25.

- 2a Llei: La línia que uneix un planeta amb el Sol escombra àrees iguals en temps iguals.

- És a dir, el planeta es desplaça més ràpidament quan està a prop del Sol (al voltant del periheli) que quan n'està allunyat (al voltant de l'afeli). Això és així perquè la gravetat del Sol accelera el planeta quan s'acosta i el desaccelera quan s'allunya. Com que les òrbites dels planetes són quasi-circulars aquest efecte no es nota gaire. És molt més evident, però, en les òrbites dels cometes, que tenen òrbites molt excèntriques.

- 3a Llei: El quadrat del període orbital d'un planeta és directament proporcional al cub del semieix major de la seva òrbita.

- Quant menor és la distància mitjana Sol-planeta, menys tarda aquest en completar la seva òrbita: Mercuri es mou més ràpid que Venus, Venus més ràpid que la Terra,... i així successivament fins a Plutó que tarda 248 anys en donar una volta al Sol.

Kepler va enunciar aquestes lleis per a les òrbites dels planetes al voltant del Sol però, de forma més general, són vàlides per a qualsevol cos que n'orbiti a un altre sempre que la massa del cos orbitant sigui negligible respecte a la massa del cos central. Això es compleix per als planetes respecte al Sol i per a la majoria de satèl·lits respecte als seus corresponents planetes. Una altra limitació d'aquestes lleis és que no funcionen bé en un sistema de més de dos cossos. Per exemple, en el cas del sistema Sol-Terra-Lluna l'aproximació no és gaire bona. Per a calcular l'òrbita de la Lluna, el mètode empíric inventat per Ptolemeu fa més de dos mil anys és més exacte que les lleis de Kepler. Isaac Newton va generalitzar les lleis de Kepler per als cossos amb una velocitat major que la velocitat d'escapament i que, per tant, no tindran una òrbita el·líptica sinó parabòlica o hiperbòlica. En aquests casos, la segona llei continua sent vàlida però la tercera llei no és aplicable perquè, en ser òrbites obertes, el moviment no serà periòdic.