Gos: diferència entre les revisions

NOMÉS ÉS UNA PROVA |

|||

| Línia 337: | Línia 337: | ||

[[zh-yue:狗]] |

[[zh-yue:狗]] |

||

[[zu:Inja]] |

[[zu:Inja]] |

||

:* Xylitol, a sugar substitute found in a variety of sugar-free and dietetic cookies, mints, and chewing gum is proving highly toxic, even fatal, to dogs.<ref>{{Cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2007-03-18-xylitol-sweetener_N.htm |

|||

|title=Popular sweetener is toxic for dogs |

|||

|author=Sharon L. Peters |

|||

|date=March 19, 2007 |

|||

|accessdate=2008-08-31}}</ref> |

|||

:*A toxic dose of roasted macadamia nuts may be as little as one nut per kilogram of body weight in the dog.<ref>{{Cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.critterology.com/macadamia_nut_toxicosis_in_the_dog-157.html |

|||

|title=Macadamia Nut Toxicosis in the Dog |

|||

|author=Susan Muller Esneault, DVM |

|||

|publisher=critterology.com |

|||

|accessdate=2008-08-31}}</ref> |

|||

:*[[Alcoholic beverage]]s pose comparable hazards to dogs as they do to humans, but due to low body weight and lack of [[alcohol tolerance]] they are toxic in much smaller portions. Signs of alcohol intoxication in pets may include vomiting, wobbly gait, depression, disorientation, and/or [[hypothermia]] (low core body temperature). High doses may result in heart arrhythmias, seizures, tremors, and even death.<ref>{{Cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.my-dog.info/dog_diseases/alcohol_poisoning.asp |

|||

|title= Alcohol Poisoning in Pets |

|||

|publisher=my-dog.info |

|||

|accessdate=2008-08-31}}</ref> |

|||

Plants such as [[caladium]], [[dieffenbachia]], and [[philodendron]] will cause [[throat]] irritations that will burn the throat going down as well as coming up. [[Hops]] are particularly dangerous and even small quantities can lead to [[malignant hyperthermia]].<ref>{{cite journal | first = K. L.| last = Duncan | coauthors = W. R. Hare and W. B. Buck | date = [[1997-01-01]] | title = Malignant hyperthermia-like reaction secondary to ingestion of hops in five dogs | journal = Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association | volume = 210 | issue = 1 | pages = 51–4 | pmid = 8977648}}</ref> [[Amaryllis]], [[narcissus (genus)|daffodil]], [[hedera helix|english ivy]], [[Iris (plant)|iris]], and [[tulip]] (especially the bulbs) causes [[stomach|gastric]] irritation and sometimes [[central nervous system]] excitement followed by [[coma]], and, in severe cases, even death. Ingesting [[digitalis|foxglove]], [[Lily of the Valley]], [[Ranunculaceae|larkspur]], and [[nerium oleander|oleander]] can be life threatening because the [[circulatory system|cardiovascular]] system is affected. [[Yew]] is very dangerous because it affects the [[nervous system]]. Immediate veterinary treatment is required for dogs that ingest these. |

|||

*Household poisons. Many household cleaners such as [[ammonia]], [[bleach]], [[disinfectants]], [[drain cleaner]], [[soap]]s, [[detergent]]s and other cleaners, [[mothball]]s, and [[match]]es are dangerous to dogs, as are cosmetics such as [[deodorant]]s, [[hair coloring]], [[nail polish]] and remover, [[perm (hairstyle)|home permanent]] lotion, and [[suntan lotion]].{{dn}} Dogs find some poisons attractive, such as [[antifreeze]] (automotive coolant), [[molluscicide|slug and snail bait]], [[insect]] bait, and [[rodent]] poisons. [[Antifreeze]] is insidious to dogs, either puddled or even partly cleaned residue, because of its sweet taste. A dog may pick up antifreeze on its fur and then lick it off. |

|||

Animal feces. Dogs occasionally eat their own feces, or the feces of other dogs and other species if available, such as cats, deer, cows, or horses. This is known as [[coprophagia]]. Some dogs develop preferences for one type over another. There is no definitive reason known, although boredom, hunger, and nutritional needs have been suggested. Eating cat feces is common, possibly because of the high protein content of cat food. Dogs eating cat feces from a litter box may lead to [[Toxoplasmosis]]. Dogs seem to have different preferences in relation to eating feces. Some are attracted to the stools of deer, cows, or horses.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.petlibrary.co.uk/dog-care/why-do-dogs-eact-poop.html|title=Why do dogs eat poop.}}</ref> |

|||

*Other risks. Human medications may be [[toxicity|toxic]] to dogs, for example [[paracetamol]]/acetaminophen (Tylenol). [[Zinc]] toxicity, mostly in the form of the ingestion of [[Cent (United States coin)|US cents]] minted after 1982, is commonly fatal in dogs where it causes a severe [[hemolytic anemia]].<ref>Stowe CM, Nelson R, Werdin R, et al: Zinc phosphide poisoning in dogs. JAVMA 173:270, 1978</ref> Some wet dog and cat food was recalled by [[Menu Foods]] in 2007 because it contained a dangerous substance.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.menufoods.com/recall/index.html |title=Recall Information |accessdate = 2008-03-08 |format=HTML |publisher=Menu Foods Income Fund }}</ref> |

|||

===Spaying and neutering=== |

|||

{{Main|Spaying and neutering}} |

|||

[[Image:Wilde huendin am stillen.jpg|right|thumb|A wild dog from Sri Lanka nursing her four puppies.]] |

|||

Neutering (spaying females and castrating males) refers to the [[Sterilization (surgical procedure)|sterilization]] of animals, usually by removal of the male's [[testicle]]s or the female's [[ovary|ovaries]] and [[uterus]], in order to eliminate the ability to procreate and reduce sex drive. Because of the overpopulation of dogs in some countries, animal control agencies, such as the [[ASPCA]], advise that dogs not intended for further breeding should be neutered, so that they do not have undesired puppies that may have to be destroyed later<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.aspca.org/site/PageServer?pagename=adopt_spayneuter |

|||

|title=Top 10 reasons to spay/neuter your pet |

|||

|publisher=American Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals |

|||

|accessdate = 2007-05-16}}</ref>. |

|||

Neutering has benefits in addition to eliminating the ability to procreate. Neutering reduces problems caused by hyper sexuality, especially in male dogs <ref>{{cite journal |author=Heidenberger E, Unshelm J |title=Changes in the behavior of dogs after castration |language=German |journal=Tierärztliche Praxis |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=69–75 |year=1990 |pmid=2326799 |doi=}}</ref>. Spayed female dogs are less likely to develop some forms of cancer, affecting [[mammary glands]], [[ovaries]] and other reproductive organs <ref>{{cite book|author=Morrison, Wallace B.|title=Cancer in Dogs and Cats (1st ed.)|publisher=Williams and Wilkins|year=1998|isbn=0-683-06105-4}}</ref>. |

|||

Neutering can also have undesireable medical effects on the animal. Neutering increases the risk of [[urinary incontinence]] in females<ref>{{cite journal |author=Arnold S |title=Urinary incontinence in castrated bitches. Part 1: Significance, clinical aspects and etiopathogenesis |language=German |journal=Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. |volume=139 |issue=6 |pages=271–6 |year=1997 |pmid=9411733 |doi=}}</ref> and [[prostate cancer]] in males.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Johnston SD, Kamolpatana K, Root-Kustritz MV, Johnston GR |title=Prostatic disorders in the dog |journal=Anim. Reprod. Sci. |volume=60-61 |issue= |pages=405–15 |year=2000 |pmid=10844211 |doi=10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00101-9}}</ref> |

|||

The hormonal changes involved with sterilization are likely to somewhat change the animal's personality, along with metabolism. Recent studies proved that spayed and neutered dogs in general are more aggressive towards people and other dogs, as well as more fearful and sensitive to touch than dogs than had not been sterilized<ref>{{cite conference |first= Deborah L. last= Duffy, Ph.D.| |coauthors=James A. Serpell, Ph.D |title= Non-reproductive Effects of Spaying and Neutering |

|||

on Behavior in Dogs |publisher=Third International Symposium on Non-Surgical |

|||

Contraceptive Methods for Pet Population Control |date=2006 |location=Center for the Interaction of |

|||

Animals and Society, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania |url=http://www.naiaonline.org/pdfs/LongTermHealthEffectsOfSpayNeuterInDogs.pdf}} </ref>, though individual effects may vary. |

|||

Dogs are often altered prior to reaching sexual maturity and so never experience a heat cycle. Studies consistently show that neutering male dogs prior to sexual maturity is associated with no major risks and a number of medical benefits.<ref name="howe">{{cite journal |

|||

| journal=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association |

|||

| date=2001 |

|||

| volume=218 |

|||

| pages=217-221 |

|||

| doi=10.2460/javma.2001.218.217 |

|||

| title=Long-term outcome of gonadectomy performed at an early age or traditional age in dogs |

|||

| author=Lisa M. Howe, Margaret R. Slater, Harry W. Boothe, H. Phil Hobson, Jennifer L. Holcom, Angela C. Spann}} |

|||

</ref><ref name="spain">{{cite journal |

|||

| date=2004 |

|||

| volume=224 |

|||

| pages=380-387 |

|||

| doi=10.2460/javma.2004.224.380 |

|||

| author=C. Victor Spain, Janet M. Scarlett, Katherine A. Houpt |

|||

| title=Long-term risks and benefits of early-age gonadectomy in dogs |

|||

| journal=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association |

|||

}} </ref><ref name="hagen"/>. In females, however, there is evidence that spaying prior to sexual maturity can have both positive and negative medical effects. For example, if they are spayed before their first [[estrus cycle|heat cycle]], female dogs are less likely to develop certain reproductive organ deseases such as [[Canine_venereal_sarcoma]], [[Brucellosis]] etc. |

|||

Spaying or neutering very young animals, also known as early-age spay, can result in increased health concerns later on in life for both sexes <ref>{{cite conference |first=CV |last= Spain| coauthors=JM Scarlett, KA Houpt |title=Long-term risks and benefits of pediatric |

|||

gonadectomy in dogs. |publisher= Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association |date=2004 |url=http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2004.224.380?prevSearch=authorsfield%3A%28Scarlett%2C+Janet+M.%29&searchHistoryKey= |id= 224(3): |

|||

380-387}} </ref>. Incontinence in female dogs is made worse by spaying too early<ref name="spain"/>. In both males and females, alteration causes changes in hormones during development. This inhibits the natural signals needed for proper body development, leading to larger animals with greater risk for hip dysplasia, osteoporosis and other joint disorders <ref> |

|||

{{cite conference |first=MAE |last van Hagen|coauthors=, BJ Ducro, J van den Broek, et al |title=Incidence, risk factors, and |

|||

heritability estimates of hind limb lameness caused by hip dysplasia in a birth cohort of |

|||

Boxers.|publisher=American Journal of Veterinary Research |date=2005 |url=http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.307|id=66(2):307-312 }} </ref>. These findings suggest that although male dogs can be altered even before three months, female dogs should be spayed closer to six months<ref name="howe"/>. |

|||

===Overpopulation=== |

|||

According to the Humane Society of the United States, 3–4 million dogs and cats are [[euthanasia|put down]] each year in the United States and many more are confined to cages in shelters because there are many more animals than there are homes. Spaying or castrating dogs helps keep overpopulation down.<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| quotes = Although the cause of pet overpopulation is multifaceted, failure of owners to spay and castrate their animals is a major contributing factor. |

|||

| last = Mahlow |

|||

| first = Jane C. |

|||

| year = 1999 |

|||

| title = Estimation of the proportions of dogs and cats that are surgically sterilized |

|||

| journal = Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (excerpt quoted by spayusa.org) |

|||

| volume = 215 |

|||

| pages = 640–643 |

|||

| url = http://www.spayusa.org/main_directory/02-facts_and_education/stats_surveys/javma_articles/02dogs-cats-sterilized.asp |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-11-30 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Local humane societies, SPCAs and other animal protection organizations urge people to neuter their pets and to adopt animals from shelters instead of purchasing them. Several notable public figures have spoken out against animal overpopulation, including [[Bob Barker#Animal rights|Bob Barker]]. On his [[game show]], ''[[The Price Is Right (U.S. game show)|The Price Is Right]]'', Barker stressed the problem at the end of every episode, saying: "Help control the pet population. Have your pets spayed or neutered." The current host, [[Drew Carey]], makes a similar plea at the conclusion of each episode. |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

==Behavior and intelligence== |

|||

{{main|Dog behavior}} |

|||

{{see|:Category:Dog training and behavior}} |

|||

Although dogs have been the subject of a great deal of [[Behaviorism|Behaviorist]] psychology (e.g., [[Classical_conditioning#Pavlov.27s_experiment|Pavlov's Dog]]), they do not enter the world with a psychological "blank slate"<ref name="coren"/>. Rather, dog behavior is affected by genetic factors as well as environmental factors<ref name="coren"/>. Domestic dogs exhibit a number of behaviors and predispositions that were inherited from wolves<ref name="coren"/>. The [[grey wolf]] is a social animal that has evolved a sophisticated means of communication and social structure. The domestic dog has inherited some of these predispositions, but many of the salient characteristics in dog behavior have been largely shaped by selective breeding by humans. Thus, some of these characteristics, such as the dog's highly developed [[social cognition]], are found only in primitive forms in [[grey wolves]]<ref name="hare"/>. |

|||

===Intelligence=== |

|||

{{main|Dog intelligence}} |

|||

[[Image:Border Collie liver portrait.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The [[Border Collie]] is considered to be one of the most intelligent breeds, along with Poodle, Golden Retriever, German Shepherd and Dobermann Pinscher]] |

|||

[[Intelligence]] is an umbrella term that encompasses the faculties involved in a wide range of mental tasks, such as learning, problem-solving, communication. The domestic dog has a predisposition to exhibit a social intelligence that is uncommon in the animal world<ref name="coren"/>. Dogs, like humans, are capable of learning in a number of ways. In addition to simple [[reinforcement learning]] (e.g., [[classical conditioning|classical]] or [[operant conditioning]]), dogs are capable of learning by observation<ref name="coren"/>. |

|||

For instance, handlers of working dogs such as herding dogs and sled dogs have long known that pups learn behaviors quickly by following examples set by experienced dogs<ref name="coren"/>. Many of these behaviors are [[allelomimetic]] in that they depend on an genetic predisposition to learn and imitate behaviors of other dogs<ref name="coren"/>. This form of intelligence is not peculiar to those tasks dogs have been bred to perform, but can be generalized to myriad abstract problems. Adler & Alder demonstrated this by giving Dachshund puppies the task of learning to pull a cart by tugging on an attached piece of ribbon in order to get a reward in the cart. Puppies that watched an experienced dog successfully retrieve the reward in this way learned the task fifteen times faster than those who were left to solve the problem on their own<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|journal=Developmental Psychobiology |

|||

|Volume =10 |

|||

|page= 267-271 |

|||

|year=2004 |

|||

|title = Ontogeny of observational learning in the dog (Canis familiaris) |

|||

|authorDr. Leonore Loeb Adler, Helmut E. Adler |

|||

|url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/109705129/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0 |

|||

}}</ref><ref name="coren"/>. In addition to learning by example from other dogs, dogs have also been shown to learn by mimicking human behaviors. In another study, puppies were presented with a box, and shown that when a handler pressed a lever, a ball would roll out of the box. The handler then allowed the puppy to play with the ball, making it an intrinsic reward. The pups were then allowed to interact with the box. Roughly three quarters of puppies subsequently touched the lever, and over half successfully released the ball<ref name="hungary">{{cite journal |

|||

|author=Kubinyi, E., Topal, J., & Miklosi, A. |

|||

|year=2003 |

|||

|title=Dogs (canis familiaris) learn their owners via observation in a manipulation task. |

|||

|journal=Journal of Comparative Psychology |

|||

|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12856786 |

|||

}}</ref>. This is compared to only 6 percent in a control group that did not watch the human manipulate the lever. Furthermore, the ability for dogs to learn by example has been shown to be as effective operant conditioning. McKinley and Young have demonstrated that dogs show equivalent accuracy and learning times when taught to identify an object by operant conditioning as they do when taught by human example. In this study, it was found that handing an object between experimenters who then use its name in a sentence successfully taught an observing dog each objects name, allowing them to subsequently retrieve the item<ref name="mckinley">{{cite journal |

|||

|title=The efficacy of the model-rival method when compared to operant conditioning for training domestic dogs to perform a retrieval-selection task. |

|||

|journal=AABS |

|||

|year=2003 |

|||

}}</ref>. |

|||

Studies have shown that the learning to mimic other dogs or humans is not limited to classical conditioning. Rather, dogs demonstrate a sophisticated [[social cognition]], by associating behavioral cues with abstract meanings<ref name="coren"/>. One such class of cognition that involves the understanding that others are conscious agents, often referred to as [[theory of mind]], is an area where dogs excel. Research has shown that dogs are capable of interpreting subtle social cues, and appear to recognize when a human or dog's attention is focused on them. For instance, researchers devised a task in which a reward was hidden under one of two buckets. The experimenter then attempted to communicate with the dog to indicate the location of the reward by using a wide range of signals: tapping the bucket, pointing to the bucket, nodding to the bucket or simply [[saccade|saccading]] to the bucket<ref name="hare">{{cite journal |

|||

|author=Hare, B., Brown, M., Williamson, C., & Tomasello, M. |

|||

|year=2002 |

|||

|title=The domestication of social cognition in dogs |

|||

|journal=Science |

|||

|year=2002 |

|||

}}</ref>. Results showed that domestic dogs were better than [[chimpanzee]]s, [[grey wolf|wolves]] and even human infants at this task, even when the experimenter indicated the location of the reward with only their eyes. Further, even young puppies with limited exposure to humans performed well on this task<ref name="coren"/>. These results demonstrate that the social cognition of dogs can exceed that of even our closest genetic relatives, and that this capacity is a recent genetic acquisition that distinguishes the dog from its ancestor, the wolf<ref name="coren"/>. Studies have also investigated whether dogs engaged in dyadic play change their behavior depending on the attentional state of their partner<ref name="ach">{{cite journal |

|||

|title= Attention to attention in domestic dog ( Canis familiaris ) dyadic play |

|||

|journal=Journal Animal Cognition |

|||

|publisher=Springer Berlin / Heidelberg |

|||

|Volume=12 |

|||

|year=2009 |

|||

|url=http://www.springerlink.com/content/r338v42481024317}} |

|||

</ref>. These studies show that play signals were only sent when the dog was holding the attention of its partner. If the partner was distracted, the dog instead engaged in attention-getting behavior before sending a play signal<ref name="ach"/>. Dr. [[Stanley Coren]], an expert on the subject of dog psychology, has argued that dogs demonstrate a sophisticated theory of mind by engaging in deception. Due to the difficulty in producing deceptive behavior in the lab, Coren supports this position with a number of anecdotes, including one example where a dog hid a stolen treat by sitting on it until the rightful owner of the treat left the room<ref name="coren"/>. Although this could have been accidental, Coren suggests that the thief understood that the treat's owner would be unable to find the treat if it were out of view. Together, the empirical data and anecdotal evidence points to dogs possessing at least a limited form of theory of mind<ref name="coren"/><ref name="ach"/>. |

|||

====Development==== |

|||

Like human children, dogs go through a series of stages of cognitive development<ref name="coren"/>. For instance, dogs, like humans, are not born with an understanding of [[object permanence]], the understanding that objects that are not being actively perceived remain in existence<ref name="coren"/>. In both species, an understanding of object permanence occurs during as the infant is learning the coordination of secondary circular reactions, as described by [[Jean Piaget]]. That is, as the infants learn to interact intentionally with objects around it. For dogs, this occurs at roughly 8 weeks of age (as compared to 18 months in human children)<ref name="coren"/> |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

===Interactions with humans=== |

|||

[[Image:Caynsham-beagles.jpg|left|thumb|A hunter with a large pack of [[beagle]]s, a breed of hunting dogs]] |

|||

Domestic dogs inherited a complex social hierarchy and behaviors from their ancestor, the wolf<ref name="ADW"/>. Dogs are pack animals with a complex set of behaviors related to determining the dogs position in the social hierarchy. Dogs exhibit various postures and other means of [[nonverbal communication]] that reveal their states of mind<ref name="ADW"/>. These sophisticated forms of [[social cognition]] and communication may account for their trainability, playfulness, and ability to fit into human households and social situations<ref name="miklosi"/>. These attributes have earned dogs a unique relationship with humans despite being potentially dangerous [[Apex predator]]s<ref name="miklosi"/>. |

|||

Although experts largely disagree over the details of dog domestication, it is agreed that human interaction played a significant role in shaping the subspecies<ref name="miklosi"/>. Shortly after domestication, dogs became ubiquitous in human populations, and spread throughout the world<ref name="miklosi"/>. Emigrants from Siberia likely crossed the [[Bering Strait]] with dogs in their company, and some experts suggest that use of sled dogs may have been critical to the success of the waves that entered North America roughly 12,000 years ago<ref name="history">{{cite book |

|||

|title=A dogs history of America |

|||

|author=Mark Derr |

|||

|year=2004 |

|||

|publisher=North Point Press |

|||

}}</ref> Dogs were an important part of life for the [[Athabascan]] population in North America. For many groups, the dog was the only domesticated animal<ref name="history"/>. Dogs were used by Athabascan emmigrants again 1,400 years ago, when they carried much of the load in the migration of the [[Apache]] and [[Navajo]] tribes. Use of dogs as pack animals in these cultures often persisted after the introduction of the [[horse]] to North America<ref name="history"/>. |

|||

Dogs have lived and worked with humans in so many roles that they have earned the unique [[sobriquet]] "man's best friend",<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.almostheaven-golden-retriever-rescue.org/old-drum.html |

|||

| title = The Story of Old Drum |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-11-29 |

|||

| publisher = Cedarcroft Farm Bed & Breakfast — Warrensburg, MO |

|||

}}</ref> a term which is used in other languages as well as in [[Icelandic language|Icelandic]] (“[[wikt:besti vinur mannsins|besti vinur mannsins]]”). |

|||

====Work and sport==== |

|||

[[Image:American water spaniel 01.jpg|thumb|right|Many dogs, such as this [[American Water Spaniel]], have had their natural hunting instincts suppressed or altered to suit human needs.]] |

|||

Dogs have traditionally been used for a variety of tasks since their domestication by early man. Dogs have been bred for herding livestock<ref>{{cite book|last=Williams|first=Tully|title=Working Sheep Dogs}}</ref>, different kinds of hunting (e.g., pointers, hounds)<ref>{{cite book|last=Serpell|first=James|title=The Domestic Dog|chapter=Origins of the dog: domestication and early history}}</ref>, keeping living spaces clear of rats <ref name="ADW">Dewey, T. and S. Bhagat. 2002. "Canis lupus familiaris" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed January 06, 2009 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Canis_lupus_familiaris.html. |

|||

</ref>, guarding, helping fishermen with nets, and pulling loads in addition to their roles as companions<ref name="ADW"/>. |

|||

More recently, many dogs have taken on a number of roles under the general classification of [[Service Dogs|service]] dogs. Service dogs provide assistance to individuals with disabilities (either physical or mental<ref>http://www.psychdog.org/attclinicians.html</ref><ref>http://www.assistancedogsinternational.org/guide.php</ref>). These roles include guide dogs, utility dogs, assistance dogs, hearing dogs and psychological therapy dogs. Some dogs have even been shown to alert their handler when the handler shows signs of an impending seizure. Some can achieve this well in advance of the onset of the seizure, allowing the owner to seek safety, medication or medical care<ref name="seizure">{{cite journal| |

|||

title=Seizure-alert dogs: a review and preliminary study| |

|||

journal =Seizure| |

|||

volume=12| |

|||

author=D. Dalziel}}</ref> |

|||

Owners of dogs often enter them in competitions,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.akc.org/events/conformation/beginners.cfm|title=A Beginner's Guide to Dog Shows|publisher=American Kennel Club|accessdate=2008-10-30}}</ref> whether show (breed conformation shows) or [[dog sports|sports]], including dog racing & dog sledding. |

|||

Conformation shows, also referred to as breed shows, are a kind of dog show in which a judge familiar with a specific dog breed evaluates individual purebred dogs for how well the dogs conform to the established breed type for their breed, as described in a breed's individual breed standard. As the breed standard has only to do with the externally observable qualities of the dog such as appearance, movement, and temperament, separately tested for qualities such as tests for ability in specific work or dog sports, tests for genetic health, tests for general health or specific tests for inherited disease, or any other specific tests for characteristics that cannot be directly observed, are not part of the judging in conformation shows. |

|||

===Behaviour=== |

|||

Dogs tend to be poorer than wolves and [[coyote]]s at [[observational learning]], being more responsive to [[instrumental conditioning]].<ref name="DOGS">{{cite book | author= Coppinger, Ray | title=Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution | year=2001 | isbn=0684855305 | publisher= Scribner | location= New York | page= 352 }}</ref> Feral dogs show little of the complex social structure or dominance hierarchy present in wolf packs. For dogs, other members of their kind are of no help in locating food items, and are more like competitors.<ref name="DOGS">{{cite book | author= Coppinger, Ray | title=Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution | year=2001 | isbn=0684855305 | publisher= Scribner | location= New York | page= 352 }}</ref> Feral dogs are primarily scavengers, with studies showing that unlike their wild cousins, they are poor [[ungulate]] hunters, having little impact on wildlife populations where they are [[sympatric]]. Free ranging pet dogs however are more prone to predatory behaviour toward wild animals. Feral dogs have been reported to be effective hunters of reptiles in the [[Galapagos islands]].<ref name="Evolution">{{cite book | author= Serpell, James| title=The Domestic Dog; its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people | year=1995 | isbn=0-521-42537-9 | publisher= Cambridge Univ. Press | location= Cambridge | page= 267 }}</ref> Despite common belief, domestic dogs can be [[monogamous]].<ref name=Pal>{{cite journal |author=Pal SK |title=Parental care in free-ranging dogs, Canis familiaris |journal=Applied Animal Behaviour Science |volume=90 |issue=1 |pages=31–47 |year=2005 |month=January |doi=10.1016/j.applanim.2004.08.002 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168159104001753}}</ref> Breeding in feral packs can be, but does not have to be restricted to a dominant alpha pair (despite common belief, such things also occur in wolf packs).<ref>Günther Bloch: Die Pizza-Hunde. ISBN 9783440109861</ref> Male dogs are unusual among canids by the fact that they mostly seem to play no role in raising their puppies, and do not kill the young of other females to increase their own reproductive success.<ref name="Evolution">{{cite book | author= Serpell, James| title=The Domestic Dog; its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people | year=1995 | isbn=0-521-42537-9 | publisher= Cambridge Univ. Press | location= Cambridge | page= 267 }}</ref> Some sources say that dogs differ from wolves and most other large canid species by the fact that they do not regurgitate food for their young, nor the young of other dogs in the same territory.<ref name="DOGS">{{cite book | author= Coppinger, Ray | title=Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution | year=2001 | isbn=0684855305 | publisher= Scribner | location= New York | page= 352 }}</ref> However, this difference was not observed in all domestic dogs. Regurgitating of food by the females for the young as well as care for the young by the males has been observed in domestic dogs, dingos as well as in other feral or semi-feral dogs. Regurgitating of food by the females and direct choosing of only one mate has been observed even in those semi-feral dogs of direct domestic dog ancestry. Also regurgitating of food by males has been observed in free-ranging domestic dogs.<ref name=Pal/><ref>Eberhard Trumler, Mit dem Hund auf du; Zum Verständnis seines Wesens und Verhaltens; 4. Auflage Januar 1996; R. Piper GmbH & Co. KG, München</ref> |

|||

===Trainability=== |

|||

Dogs display much greater tractability than tame wolves, and are generally much more responsive to coercive techniques involving fear, aversive stimuli and force than wolves, which are most responsive toward positive conditioning and rewards.<ref name="training" /> Unlike tame wolves, dogs tend to respond more to voice than hand signals.<ref name="training2">{{cite web | url= http://www.wolfpark.org/training/Example-1.html| title= Wolf Training and Socialisation: Example #1 | publisher= Wolf Park| accessdate= 2008-10-30|format=HTML}}</ref> Although they are less difficult to control than wolves, they can be comparatively more difficult to teach than a motivated wolf.<ref name="training">{{cite web | url= http://www.wolfpark.org/wolfdogs/Poster_section7.html| title= Are wolves and wolfdog hybrids trainable? | publisher= Wolf Park| accessdate= 2008-10-30|format=HTML}}</ref> |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

* Abrantes, Roger (1999). ''Dogs Home Alone''. Wakan Tanka, 46 pages. ISBN 0-9660484-2-3 (paperback). |

|||

* A&E Television Networks (1998). ''Big Dogs, Little Dogs: The companion volume to the A&E special presentation'', A Lookout Book, GT Publishing. ISBN 1-57719-353-9 (hardcover). |

|||

* Alderton, David (1984). ''The Dog'', Chartwell Books. ISBN 0-89009-786-0. |

|||

*Bloch, Günther. ''Die Pizza-Hunde'' (in German), 2007, Franckh-Kosmos-Verlags GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart,ISBN 9783440109861 |

|||

* Brewer, Douglas J. (2002) ''Dogs in Antiquity: Anubis to Cerberus: The Origins of the Domestic Dog'', Aris & Phillips ISBN 0-85668-704-9 |

|||

* Coppinger, Raymond and Lorna Coppinger (2002). ''Dogs: A New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution'', University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-11563-1 |

|||

*Cunliffe, Juliette (2004). ''The Encyclopedia of Dog Breeds''. Parragon Publishing. ISBN 0-7525-8276-3. |

|||

* Derr, Mark (2004). ''Dog's Best Friend: Annals of the Dog-Human Relationship''. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14280-9 |

|||

* Donaldson, Jean (1997). ''The Culture Clash''. James & Kenneth Publishers. ISBN 1-888047-05-4 (paperback). |

|||

*Fogle, Bruce, DVM (2000). ''The New Encyclopedia of the Dog''. Doring Kindersley (DK). ISBN 0-7894-6130-7. |

|||

*Grenier, Roger (2000). ''The Difficulty of Being a Dog''. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-30828-6 |

|||

* Milani, Myrna M. (1986). ''The Body Language and Emotion of Dogs: A practical guide to the Physical and Behavioral Displays Owners and Dogs Exchange and How to Use Them to Create a Lasting Bond'', William Morrow, 283 pages. ISBN 0-688-12841-6 (trade paperback). |

|||

* Pfaffenberger, Clare (1971). ''New Knowledge of Dog Behavior''. Wiley, ISBN 0-87605-704-0 (hardcover); Dogwise Publications, 2001, 208 pages, ISBN 1-929242-04-2 (paperback). |

|||

* Shook, Larry (1995). "Breeders Can Hazardous to Health", ''The Puppy Report: How to Select a Healthy, Happy Dog'', Chapter Two, pp. 13–34. Ballantine, 130 pages, ISBN 0-345-38439-3 (mass market paperback); Globe Pequot, 1992, ISBN 1-55821-140-3 (hardcover; this is much cheaper should you buy). |

|||

* Shook, Larry (1995). ''The Puppy Report: How to Select a Healthy, Happy Dog'', Chapter Four, "Hereditary Problems in Purebred Dogs", pp. 57–72. Ballantine, 130 pages, ISBN 0-345-38439-3 (mass market paperback); Globe Pequot, 1992, ISBN 1-55821-140-3 (hardcover; this is much cheaper should you buy). |

|||

* Thomas, Elizabeth Marshall (1993). ''The Hidden Life of Dogs'' (hardcover), A Peter Davison Book, Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-66958-8. |

|||

*Trumler, Eberhard. ''Mit dem Hund auf du; Zum Verständnis seines Wesens und Verhaltens'' (in German); 4. Auflage Januar 1996; R. Piper GmbH & Co. KG, München |

|||

*''Small animal internal medicine'', RW Nelson, Couto page 107 |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{sisterlinks}} |

|||

{{Wikispecies}} |

|||

*[http://www.akc.org/ American Kennel Club] |

|||

*[http://www.ankc.org.au/home/breeds.asp Australian National Kennel Club] |

|||

* [http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/name/Canis_lupus_familiaris Biodiversity Heritage Library bibliography] for ''Canis lupus familiaris'' |

|||

*[http://www.ckc.ca/ Canadian Kennel Club] |

|||

*[http://www.fci.be/home.asp?lang=en Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) - World Canine Organisation] |

|||

*[http://www.nzkc.org.nz/dogselect.html New Zealand Kennel Club] |

|||

*[http://www.the-kennel-club.org.uk/ The Kennel Club (UK)] |

|||

Revisió del 21:05, 7 feb 2009

| Canis lupus familiaris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Enregistrament | |

| Dades | |

| Principal font d'alimentació | Proteïna |

| Font de | dog milk (en) |

| Esperança de vida | 9 anys |

| Longevitat màxima | 30 anys |

| Taxonomia | |

El gos, ca o cutxo (Canis lupus familiaris) és un mamífer domèstic de la família dels cànids. Les proves arqueològiques demostren que el gos ha estat en convivència propera amb els humans des de fa com a mínim 9.000 anys, però possiblement des de fa 14.000 anys.[1] Les proves fòssils demostren que els avantpassats dels gossos moderns ja estaven associats amb els humans fa 100.000 anys.[2]

A les Illes Balears i a parts de la Catalunya Nord el gos rep el nom de ca, que prové directament del mot llatí canis, que al seu torn prové de la forma protoindoeuropea *kwon-[3]. Una de les variacions d'aquesta forma indoeuropea és cuon, que a través del grec antic κύων ha portat a termes de la llengua catalana com ara "cinisme" o "cinocefàlia". L'arrel llatina es reflecteix en altres llengües romàniques: chien, cane, can, câine, cão, etc. D'altra banda, el terme més estès als Països Catalans per referir-se a aquest animal, gos, té un origen expressiu a partir de l'expressió "gus" o "kus", utilitzada antigament per a cridar o dirigir-se als gossos. És atestat per primer cop l'any 1342.[4]

N'hi ha aproximadament 800 races (més que qualsevol altre animal[5]) que varien significativament en dimensions, fisonomia i temperament, i que presenten una gran varietat de colors i de tipus de pèl diferents. Tenen una gran relació amb els humans, servint d'animals de companyia, d'animals de guàrdia, de gossos pigall o de gossos pastors, per exemple.

Amb un nombre estimat de 400 milions de gossos en llars d'arreu del món, és un dels animals de companyia més populars, probablement només superat pels gats.[6] Es creu que el llop gris, del qual és considerat una subespècie, n'és l'avantpassat més immediat.[7] Les investigacions més recents indiquen que el gos fou domesticat per primera vegada a l'est d'Àsia, possiblement a la Xina;[8] tanmateix, és incert si tots els gossos domèstics provenen d'un mateix grup o si el procés de domesticació es repetí diversos cops.

Nomenclatura

Existeixen diverses formes per referir-se a un grup d'animals. Són comuns els substantius col·lectius: bandada (ocells), porcada (porcs) o banc (peixos). En el cas dels gossos, el terme correcte en català per referir-se a un grup d'ells, especialment quan cacen junts, és "gossada".[9] Per referir-se a una cria de gos, el terme correcte és "cadell", un terme que posteriorment s'ha estès per a denominar les cries d'altres mamífers carnívors com el lleó, l'ós o el llop.

Els gossos els avantpassats dels quals es troben registrats formalment són denominats com a gats amb pedigrí. En termes estrictes, un pura sang és aquell que té avantpassats de la mateixa raça, mentre que en el cas d'un gos de pedigrí és essencial l'existència d'un registre genealògic dels seus avantpassats. Aquests registres genealògics han estat criticats per grups en defensa dels animals[10] que argumenten que promou una discriminació en contra dels gossos mestissos; i per veterinaris,Error de citació: Etiqueta <ref> no vàlida;

noms no vàlids, per exemple, hi ha masses que afirmen que les associacions canines només tenen en compte la puresa de la raça del gos sense valorar-ne la salut.

Taxonomia

El gos fou descrit com a Canis familiaris i Canis familiaris domesticus per Carl von Linné a la seva obra Systema Naturae del 1758.[11] Linné utilitzà dos noms diferents perquè creia que els gossos salvatges (Canis familiaris) eren diferents dels gossos domèstics (Canis familiaris domesticus). Tanmateix, el 1993, la Smithsonian Institution i l'American Society of Mammalogists feren una revisió taxonòmica dels gossos, reclassificant-los com una subespècie del llop gris (Canis lupus).

Els gossos donen el seu nom a la família dels cànids, que inclou també els llops, les guineus, els coiots, els xacals, els gossos salvatges africans i els dingos. Es creu que aquests últims podrien formar part de la mateixa subespècie que els gossos domèstics, però provisionalment se'ls classifica dins la subespècie Canis lupus dingo.[12]

A un nivell taxonòmic més alt, també donen nom al subordre dels caniformes. Igual que els gossos, els animals que formen aquest grup comparteixen una sèrie de característiques: manquen d'urpes retràctils, tenen més dents que els feliformes (cosa que els permet processar l'aliment vegetal molt millor que els gats, per exemple), un musell llarg, carnisseres menys especialitzades que les dels fèlids, una dieta mitjanament omnívora i oportunística, i una bul·la auditiva unicameral o parcialment dividida, composta d'un únic os.

Sinònims

Aquests són noms científics invàlids, d'interès únicament històric:

aegyptius (Linnaeus, 1758), alco (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), americanus (Gmelin, 1792), anglicus (Gmelin, 1792), antarcticus (Gmelin, 1792), aprinus (Gmelin, 1792), aquaticus (Linnaeus, 1758), aquatilis (Gmelin, 1792), avicularis (Gmelin, 1792), borealis (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), brevipilis (Gmelin, 1792), cursorius (Gmelin, 1792), domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758), extrarius (Gmelin, 1792), ferus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), fricator (Gmelin, 1792), fricatrix (Linnaeus, 1758), fuillus (Gmelin, 1792), gallicus (Gmelin, 1792), glaucus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), graius (Linnaeus, 1758), grajus (Gmelin, 1792), hagenbecki (Krumbiegel, 1950), haitensis (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), hibernicus (Gmelin, 1792), hirsutus (Gmelin, 1792), hybridus (Gmelin, 1792), islandicus (Gmelin, 1792), italicus (Gmelin, 1792), laniarius (Gmelin, 1792), leoninus (Gmelin, 1792), leporarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), major (Gmelin, 1792),mastinus (Linnaeus, 1758), melitacus (Gmelin, 1792), melitaeus (Linnaeus, 1758), minor (Gmelin, 1792), molossus (Gmelin, 1792), mustelinus (Linnaeus, 1758), obesus (Gmelin, 1792), orientalis (Gmelin, 1792), pacificus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), plancus (Gmelin, 1792), pomeranus (Gmelin, 1792), sagaces (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), sanguinarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), sagax (Linnaeus, 1758), scoticus (Gmelin, 1792), sibiricus (Gmelin, 1792), suillus ( C. E. H. Smith, 1839), terraenovae (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), terrarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), turcicus (Gmelin, 1792), urcani (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), variegatus (Gmelin, 1792), venaticus Gmelin, 1792), vertegus (Gmelin, 1792)[13]

Domesticació

Basant-se en les anàlisis d'ADN, els llops avantpassats dels gossos moderns se separaren de la resta de llops fa uns cent mil anys,[14][15] i els gossos foren domesticats d'aquests llops grisos fa uns quinze mil anys.[16] Aquesta data significaria que els gossos foren la primera espècie en ser domesticada pels humans. Les proves apunten a què els gossos foren domesticats per primer cop a l'est d'Àsia, possiblement a la Xina, i algunes de les cultures que arribaren a Nord-amèrica s'endugueren gossos des d'Àsia.[8]

La relació entre els humans i els gossos es remunta al passat llunyà. Les proves arqueològiques i genètiques coincideixen en indicar que la domesticació tingué lloc a finals del Paleolític superior, a prop del límit Plistocè/Holocè, fa entre 17.000 i 14.000 anys. Ni la morfologia d'ossos fòssils, ni les anàlisis genètiques de les poblacions de gossos i llops antigues i actuals, han estat capaces fins ara de determinar amb certesa si tots els gossos són el producte d'una única domesticació, o si foren domesticats de manera independent en més d'un lloc. Els gossos domèstics podrien haver-se aparellat amb poblacions locals de llops salvatges en diverses ocasions (un procés que en genètica es coneix com a introgressió). Els gossos podrien haver estat domesticats per mitjà de diversos processos; podrien tenir l'origen en la cria de cadells de llop des de petits, fàcilment socialitzables[1] i que, després d'algunes generacions de reproduir-se entre ells, haurien donat peu a la varietat domèstica. Alternativament, els gossos podrien ser els descendents de llops menys propensos a fugir dels humans; aquesta tendència socialitzadora s'hauria anat amplificant al llarg de les generacions fins arribar a un estat de domesticació completa.[17]

Els ossos de gos més antics coneguts, dos cranis de Rússia i una mandíbula d'Alemanya, daten d'entre fa 13.000 i 17.000 anys. El seu avantpassat més probable és el gran llop holàrtic septentrional, Canis lupus lupus. Restes de gossos més petits de dipòsits en coves del Mesolític (Natufià) al Pròxim Orient, que daten de fa uns 12.000 anys, han estat interpretats com a descendents d'un llop del sud-oest d'Àsia més gràcil, Canis lupus arabs. L'art rupestre i restes d'esquelets indiquen que, fa uns 14.000 anys, els gossos s'estenien des del nord d'Àfrica, a través d'Euràsia, i fins a Nord-amèrica. Les restes de gossos enterrats al cementiri mesolític de Sværdborg (Dinamarca) suggereixen que a l'antiga Europa els gossos eren companys estimats.

Morfologia

L'enorme varietat de morfologies en les diferents races de gos fa difícil determinar la mida i el pes mitjans dels gossos. Amb una alçada d'entre 71 i 90 cm, el lloper irlandès és la raça més alta de gos[18] (tot i que alguns exemplars de gran danès superen aquesta mida, arribant fins a 107 cm).[19] La raça més petita de gos és el chihuahua, amb una mida de 15-25 cm a la creu. Amb un pes mitjà d'entre 1,5 i 3 quilograms (i que en alguns casos, pot no superar els 500 g),[20] els chihuahues també són els gossos més lleugers; els mastins anglesos i els santbernats són els gossos més pesants, amb un pes que pot arribar a més de 140 kg.[21]

La longevitat dels gossos varia d'una raça a l'altra, però en general les races més petites viuen més temps que les més grans. Els gossos més petits sovint viuen fins a l'edat de quinze o setze anys, mentre que els gossos més grans poden tenir una esperança de vida de només la meitat. Entremig s'hi troben totes les races intermitges. El gos més vell del qual es té constància, un gos ramader australià anomenat Bluey, morí l'any 1939 a l'edat de vint-i-nou anys.[22] L'esterilització de l'animal pot prolongar o escurçar-ne la vida, reduint el risc de contraure malalties com ara piomètria en les femelles o càncer testicular en els mascles. També redueix el risc d'accidents i ferides, car els gossos no esterilitzats es barallen i s'escapen més. D'altra banda, la castració dels mascles afavoreix l'aparició de càncer de pròstata, una malaltia que pot escurçar dràsticament la vida de l'animal.[23]

Diferències respecte a altres cànids

En comparació amb llops de mida equivalent, els gossos tendeixen a tenir el crani un 20% més petit i el cervell un 10% més petit, a més de tenir les dents relativament més petites que altres espècies de cànids.[6] Els gossos requereixen menys calories per viure que els llops. La seva dieta de sobres dels humans féu que els seus cervells grans i els músculs mandibulars utilitzats en la caça deixessin de ser necessaris. Alguns experts pensen que les orelles flàccides dels gossos són el resultat de l'atròfia dels músculs mandibulars.[6] La pell dels gossos domèstics tendeix a ser més gruixuda que la dels llops, i algunes tribus esquimals prefereixen la seva pell per vestir-se, degut a la seva resistència al desgast en un clima inhòspit.[6] A diferència dels llops, però igual que els coiots, els gossos domèstics tenen glàndules sudorípares als coixinets de les potes.[6] Les potes d'un gos són aproximadament la meitat de les d'un llop, i la seva cua tendeix a corbar-se cap amunt, un altre tret que no s'observa en els llops.[24]

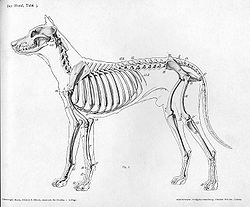

Aparell locomotor

Com la majoria de mamífers predadors, el gos té músculs potents, un sistema cardiovascular que permet una alta velocitat i una gran resistència, i dents per a caçar, aguantar i estripar les preses.

L'esquelet ancestral dels gossos els permet córrer i saltar. Les seves potes s'han desenvolupat per a impulsar-los ràpidament cap endavant, saltant quan cal, per tal de caçar i atrapar les preses. Per tant, tenen peus petits i apretats, i caminen sobre els dits (digitígrads). Les seves potes posteriors són bastant rígides i sòlides, mentre que les anteriors són laxes i flexibles, estant unides al tronc únicament per músculs.

Tot i que la cria selectiva ha canviat l'aparença de moltes races, tots els gossos conserven els elements bàsics dels seus avantpassats. Els gossos tenen omòplats desconnectats (manquen de clavícula) que permeten fer gambades més llargues. Tenen urpes vestigials a les potes anteriors i a vegades a les posteriors. En alguns casos, se'ls treuen aquestes urpes per tal d'evitar que el gos se les arranqui sense voler durant la persecució d'una presa, però aquesta pràctica és il·legal en alguns països.

Pelatge

Igual que els llops, els gossos tenen un pelatge, una capa de pèls que els cobreix el cos. El pelatge d'un gos pot ser un "pelatge doble", compost d'una capa inferior suau i una capa superior basta. A diferència dels llops, els gossos poden tenir un "pelatge únic", mancat de capa inferior. Els gossos amb un pelatge doble, com els llops, estan adaptats per a sobreviure en temperatures fredes, i tendeixen a provenir de climes més freds.

Els gossos solen presentar vestigis de contraombreig, un patró de camuflatge natural comú. La base general del contraombreig és que un animal il·luminat des de dalt apareix més clar a la meitat superior i més fosc a la meitat inferior, on normalment té el seu propi color.[25][26] Aquest és un patró que els predadors poden aprendre a reconèixer. Un animal contraombrejat té una coloració fosca a la superfície superior i una coloració fosca a la inferior.[25] Això redueix la visibilitat general de l'animal. Un vestigi d'aquest patró és que moltes races tenen una banda, una ratlla o una estrella de pelatge blanc al pit o a la part inferior.[26]

Cua

Hi ha moltes formes diferents de cua de gos: recta, recta cap amunt, forma de falç, rinxolada o en tirabuixó. En algunes races, la cua és tallada tradicionalment per a evitar ferides (especialment en els gossos de caça).[27] En algunes races, alguns cadells neixen amb una cua curta o sense cua.[28] Això passa més sovint en certes races, especialment en aquelles a les quals sovint es talla la cua, i que per tant no tenen estàndard de raça quant a la cua.

Reproducció

En els gossos domèstics, la maduresa sexual (pubertat) comença a produir-se a l'edat d'entre sis i dotze mesos tant en els mascles com en les femelles,[29][30] tot i que en algunes races de gran mida pot retardar-se fins l'edat de dos anys. L'adolescència de la majoria dels gossos dura entre els dotze i els quinze mesos d'edat, a partir dels quals ja són més adults que cadells. Com en el cas d'altres espècies domesticades, la domesticació ha afavorit una major libido i un cicle de reproducció més primerenc i freqüent en els gossos que en els seus avantpassats salvatges. Els gossos romanen reproductivament actius fins a edats avançades.

La majoria de gosses tenen el seu primer zel a l'edat d'entre sis i dotze mesos, tot i que algunes races grans no el tenen fins a l'edat de dos anys. Les femelles entren en zel dos cops per any, durant el qual el seu cos es prepara per la gestació, i al pic del qual entren en estre, el període durant el qual estan mentalment i física receptives a la copulació.[29] Com que els òvuls sobreviuen i poden ser fertilitzats durant una setmana després de l'ovulació, és possible que una femella s'aparelli amb més d'un mascle.[29]

Les gosses donen a llum 56-72 dies després de ser fertilitzades,[31][29] amb una mitjana de 63 dies, tot i que la durada de la gestació pot variar. Una ventrada mitjana consisteix en uns sis cadells,[32] tot i que aquest nombre pot variar molt segons la raça de gos. Els gossos toy donen a llum entre un i quatre cadells per ventrada, mentre que les races més grans poden donar una mitjana de dotze cadells per ventrada.

Algunes races han adquirit trets per la cria selectiva que interfereixen amb la reproducció. Els mascles de buldog francès, per exemple, són incapaços de muntar la femella. En la gran majoria de casos, les femelles d'aquesta raça han de ser inseminades artificialment per tal que es reprodueixin.[33]

Sentits

El sentits de l'olfacte i l'oïda del gos són superiors als de l'ésser humà en molts aspectes. Algunes de les seves habilitats sensorials han estat utilitzades pels humans, com per exemple l'olfacte en els gossos de caça, gossos cercadors d'explosius o gossos cercadors de drogues.

Vista

El sistema visual dels gossos s'ha desenvolupat per a ajudar-los en la caça.[34] Tot i que és difícil de mesurar, l'agudesa visual dels caniches ha estat estimada com a equivalent a una puntuació en el test d'Snellen de 20/75.[34] Tanmateix, la discriminació visual és molt superior quan es tracta d'objectes en moviment. S'ha demostrat que els gossos són capaços de distingir el seu amo d'altres persones a distàncies de més d'un quilòmetre i mig.[34] Com a caçadors crepusculars, els gossos depenen de la seva visió en condicions de poca il·luminació. Per a ajudar-los a veure-hi en l'obscuritat, els gossos tenen pupiles molt grans, una major densitat de bastonets a la fòvea, una major velocitat de parpelleig, i un tapetum lucidum reflectant.[34] El tapetum és una superfície reflectant situada rere la retina que reflecteix la llum per a donar als fotoreceptors una segona oportunitat de captar els fotons. Tot i que aquestes adaptacion serveixen per a millorar la visió en l'obscuritat, també redueixen l'agudesa visual dels gossos.[34]

Com la majoria de mamífers, els gossos són dicromats i tenen una visió en color equivalent al daltonisme vermell-verd en els humans.[35][36][37] Les diferents races de gos tenen diferents formes i mides dels ulls, i també tenen una configuració diferent de la retina.[38] Els gossos amb el musell llarg tenen una "ratlla visual" que s'estén per l'ample de la retina i que els dóna un camp molt ample de visió excel·lent, mentre que els gossos amb el musell curt tenen una area centralis – una regió central amb fins a tres vegades la densitat de terminacions nervioses de la "ratlla visual" – que els forneix una vista detallada, molt més similar a la dels humans.

Algunes races, particularment els llebrers, tenen un camp de visió de fins a 270º (comparat amb els 180º dels humans), tot i que les races de cap ample amb el musell curt tenen un camp de visió molt més estret, tan baix com 180º.[35][36] Algunes races també presenten una tendència genètica a la miopia. Tot i que la majoria de races són memmetròpiques, s'ha descobert que un de cada dos rottweilers són miops.[34]

Oïda

El camp d'audibilitat dels gossos és aproximadament de 40 Hz a 60,000 Hz.[39] Els gossos detecten sons tan greus com 16-20 Hz (en comparació amb 20-70 Hz en els humans) i també per sobre de 45 kHz[40] (en comparació amb 13-20 kHz en els humans),[39][36] i a més tenen un grau de mobilitat de les orelles que els permet determinar ràpidament l'origen exacte d'un so.[41] Divuit o més músculs poden inclinar, rotar, alçar o baixar les orelles d'un gos. A més, un gos pot detectar l'origen d'un so molt més ràpid que un humà, i sentir sons a una distància fins a quatre vegades més gran que els humans.[41] Els gossos amb una forma de l'orella més natural, com les orelles de cànids salvatges com la guineu, solen sentir-hi millor que els gossos amb les orelles més flexibles típiques de moltes races domèstiques.

Olfacte

Mentre que el cervell humà és dominat per una gran escorça visual, el cervell caní és dominat principalment per una escorça olfactiva[34] El bulb olfactiu dels gossos és unes quaranta vegades més gran que el dels humans (en proporció a la mida total del cervell).[34] Segons la raça, els gossos tenen entre 125 i 220 milions de cèl·lules olfactives esteses sobre una àrea de la mida d'un mocador de butxaca (en comparació amb 5 milions de cèl·lules esteses sobre l'àrea d'un segell en els humans).[34][42][43] Els bloodhounds en són l'excepció, amb aproximadament 300 milions de receptors olfactius.[34] Els gossos poden distingir olors a concentracions gairebé 100 millions de vegades inferiors a les que poden distingir els humans.[44]

Gust

Entre els sentits del gos, el del gust és el que menys s'ha investigat, i sovint se l'ha relacionat amb l'olfacte. Els gossos poden distingir els sabors bàsics (tot i que gairebé no distingeixen el salat[45]) de manera semblant als humans. Tanmateix, els gustos preferits poden diferir molt d'un gos a l'altre, car sembla que els gossos no trien el menjar segons el tipus de gust, sinó segons la seva intensitat (gust fort/gust suau).[46] Els primers mesos de la vida d'un gos són bastant importants en aquest sentit; els cadells que s'acostumen a provar molts gustos diferents quan són joves també desenvoluparan un gust per la varietat quan siguin adults.[46] Igual que els humans i que molts altres animals, els gossos tenen la capacitat d'associar determinats gustos amb els problemes de salut. Si un aliment el fa emmalaltir o fa que es trobi malament, el gos tendirà a evitar el gust d'aquest aliment en el futur. Això forma part d'un mecanisme de defensa instintiu, que protegeix els animals d'enverinar-se per la ingestió freqüent de substàncies tòxiques.[46]

Tacte

Els gossos utilitzen el sentit del tacte per a comunicar-se entre ells i amb altres espècies. Si es fa apropiadament, tocar un gos pot servir per a estimular-lo o relaxar-lo. Es tracta del primer sentit que es desenvolupa en els cadells nounats, i les gosses comencen a llepar i acaronar les seves cries poc després del naixement.[47] Alguns estudis han suggerit fins i tot que els gossos poden detectar moviments en l'abdomen de la mare fins i tot abans de néixer, i que les gosses que són acaronades durant la gestació donen a llum cries més dòcils.[48] Els gossos tenen sensors tàctils arreu del cos, però els coixinets, la columna vertebral i la regió de la cua són algunes de les zones més sensibles.

Les vibrisses dels gossos presenten mecanoreceptors que els serveixen per a adquirir informació tàctil del seu ambient, però aquesta funció no és tan important com ho és en els gats. Entre altres coses, serveixen per a sentir el flux de l'aire. A més del musell, on reben el nom de "bigotis", els gossos tenen vibrisses a sobre dels ulls i a sota la mandíbula.[47]

Alimentació

Nutrició

Malgrat que descendeixen dels llops, els gossos domèstics són classificats com a omnívors.[29] Que pertanyi a l'ordre dels carnívors no vol dir necessàriament que la dieta d'un gos hagi d'estar limitada a carn; a diferència dels carnívors obligats, com ara els fèlids (que tenen un intestí prim més curt), els gossos ni depenen de les proteïnes específiques de la carn ni necessiten un alt nivell de proteïna per a satisfer les seves necessitats nutricionals. Els gossos poden digerir sense problemes una gran varietat d'aliments, incloent-hi verdures i cereals; de fet, aquests aliments formen una part significativa de la seva dieta. Els cànids salvatges sovint mengen plantes i fruits.[29]

La dieta d'un gos hauria de consistir en una proporció equilibrada de proteïnes, carbohidrats, greixos i aigua. Un gos de mida mitjana necessita unes 65 calories per quilogram de pes al dia, mentre que les races més grans poden necessitar-ne només 20 i les més petites 40.[29] Els cadells tenen unes necessitats nutricionals més elevades que les dels adults; necessiten el doble de proteïnes i un 50% més de calories.[29] Els gossos poden sobreviure molt de temps sense menjar, i poden perdre fins a un 40% del seu pes corporal sense morir-se.[29] En canvi, la pèrdua del 15% de l'aigua corporal podria resultar fatal.[29] Una dieta únicament carnívora pot no ser adequada pels gossos, car manca de components vitals d'una dieta saludable.[29]

Els gossos domèstics poden viure saludablement amb una dieta vegetariana raonable i dissenyada amb cura, especialment si inclou ous i productes lactis, tot i que algunes fonts suggereixen que un gos amb una dieta estrictament vegetariana sense L-carnitina pot desenvolupar miocardiopatia dilatada.[49] Tanmateix, molts fruits secs, llavors, mongetes, verdures, fruites i cereals integrals també són una font d'L-carnitina. En estat salvatge, els gossos poden sobreviure amb una dieta vegetariana quan no poden trobar preses animals. L'observació de condicions extremament dures com ara la Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, així com estudis científics de condicions similars, han demostrat que dietes carnívores amb un alt contingut proteic (aproximadament el 40%) ajuden a evitar danys als teixits musculars en els gossos i alguns altres mamífers. Aquesta proporció de proteïnes correspon al percentatge de proteïnes de la dieta dels gossos salvatges quan les preses són abundants; sembla que nivells encara més alts de proteïna no produeixen cap benefici.

Enverinament

Alguns aliments dels humans són perillosos pels gossos, incloent-hi la xocolata (enverinament amb teobromina), les cebes, el raïm i les panses, alguns tipus de xiclets, determinats edulcorants i les nous de macadàmia.

La xocolata pot contenir grans quantitats de greixos i estimulants semblants a la cafeïna, com ara metilxantines, que, ingerides en quantitats importants, poden produir efectes nocius en gossos que van des de vòmits i diarrea fins a pantejos, una set i una micció excessives, hiperactivitat, un ritme cardíac anormal, tremolors, espasmes i fins i tot la mort en els casos més greus. Generalment, com més fosca és la xocolata, més gran és el potencial de problemes clínics per enverinament amb metilxantines. Només 570 grams de xocolata amb llet (o només 60 grams de xocolata amarga) poden causar problemes greusa un gos de 4,5 kg. La xocolata blanca pot no tenir el mateix potencial que la fosca de causar un enverinament amb metilxantina, però l'alt contingut en greixos de les xocolates més clares pot provocar vòmits i diarrea, així com el possible desenvolupament d'una pancreatitis, una inflamació del pàncrees que pot ser mortal.[50]

El perill que representen el raïm i les panses fou descobert a voltants del 2000, i ha estat fet públic lentament des d'aleshores. No se'n coneix la causa, i petites quantitats d'aquests fruits causen una insuficiència renal aguda. Les groselles també podrien ser perilloses.[51][52]

Salut

Els gossos són susceptibles a diverses malalties, trastorns i verins, alguns dels quals afecten els humans de la mateixa manera, i d'altres que són únics als gossos. Com tots els mamífers, els gossos són susceptibles a la hipertèrmia quan hi ha nivells elevats d'humiditat i/o de temperatura.[53]

Trastorns i malalties

Algunes races de gos també són propenses a determinats trastorns genètics, com ara la displàsia de maluc, luxacions rotulars, paladar leporí, ceguesa o sordesa. Els gossos també són susceptibles als mateixos trastorns que els humans, incloent-hi la diabetis, l'epilèpsia, el càncer i l'artritis. La torsió gàstrica i la meteorització són un problema seriós en algunes races de pit ample.

Les malalties infeccioses habitualment associades amb els gossos inclouen la ràbia (hidrofòbia), el parvovirus caní i el brom. Les malalties heretables dels gossos poden incloure un gran varietat, des de la displàsia de maluc i les luxacions rotulars medials fins a l'epilèpsia i l'estenosi pulmonar. Els gossos poden contraure gairebé totes les malalties que afecten els humans (tret d'aquelles que són específiques a l'espècie), com l'hipotiroïdisme, el càncer, malalties dentals, malalties cardíaques, etc. Per a protegir-los de moltes malalties comunes, sovint els gossos són vacunats.

Dos trastorns mèdics greus que afecten els gossos són la piomètria, que afecta femelles no esterilitzades de totes menes i edats, i la meteorització, que afecta les races més grans i els gossos de pit ample. Ambdós són trastorn aguts, que poden matar ràpidament. Els amos de gossos susceptibles haurien de conèixer aquests trastorns com a part de la seva cura dels animals.

Alguns paràsits externs comuns són les puces, paparres i àcars. Els paràsits interns inclouen els cucs ancilòstoms, cestodes, nematodes i dirofilaris.

Predadors

Tot i que els gossos salvatges, com els llops, són predadors alfa, poden morir en combats territorials amb animals salvatges.[54] A més a les zones en què els gossos són simpàtrics amb altres predadors grans, els gossos poden ser una font d'aliment important per cànids o fèlids grans. A Croàcia són morts més gossos que ovelles, mentre que sembla que a Rússia els llops limiten les poblacions de gossos ferals. A Wisconsin es paga una major compensació per la pèrdua de gossos que de bestiar.[54] Hi ha hagut casos en què un parell de llops maten gossos, seguint un mètode en què un d'ells atrau el gos cap a vegetació densa, on l'altre llop prepara una emboscada.[55] En alguns casos, els llops han mostrat una manca anormal de por dels humans i els edificis a l'hora d'atacar gossos, fins al punt que se'ls ha de foragitar o matar.[56] Els [coiot]]s també ataquen gossos.[57] Es coneixen casos de feres que maten gossos. Se sap que els lleopards tenen una predilecció pels gossos, i han matat i s'han menjat fins i tot gossos grans i ferotges.[58] A diferència dels lleopards que viuen a la mateixa regió, els tigres de l'Índia rarament ataquen gossos, tot i que a Manxúria, la Indoxina, Indonèsia i Malàisia, es diu que els tigres maten gossos amb el mateix vigor que els lleopards.[59] Finalment, les hienes ratllades són grans predadores de gossos als pobles del Turkmenistan, l'Índia i el Caucas.[60]

Races

Hi ha nombroses races de gos; les organitzacions cinològiques en reconeixen més de 800. Molts gossos, especialment fora dels Estats Units i d'Europa occidental, no pertanyen a cap raça reconeguda. Uns quants tipus de gos bàsics han evolucionat gradualment durant la relació del gos domèstic amb els humans al llarg dels últims 10.000 anys o més però totes les races modernes tenen un origen relativament modern. Moltes d'elles són el resultat d'un procés deliberat de selecció artificial. Degut a això, algunes races estan altament especialitzades, i hi ha una diversitat morfològica extraordinària entre races diferents. Malgrat aquestes diferències, els gossos són capaços de distingir els altres gossos d'altres tipus d'animal.

La definició del que és una raça de gos és tema d'una certa polèmica. Depenent de la mida de la població fundadora original, les races amb un patrimoni gènic reduït poden tenir problemes de consanguinitat, concretament degut a l'efecte fundador. Els criadors de gossos prenen cada cop més consciència de la importància de la genètica de poblacions i de mantenir patrimonis gènics diversos. Les proves de salut i noves proves d'ADN poden contribuir a evitar problemes, oferint un substitut de la selecció natural. Sense selecció, els patrimonis gènics consanguinis o tancats poden augmentar el risc de greus problemes de salut o de comportament. Algunes organitzacions defineixen una raça menys estrictament, de manera que un exemplar pot ser considerat d'una raça sempre que el 75% de la seva ascendència sigui d'aquesta raça. Aquestes consideracions afecten tant els animals de companyia com els gossos que participen en exposicions canines. Fins i tot gossos amb pedigrí que han estat premiats pateixen de defectes genètics esguerradores a causa de l'efecte fundador o la consanguinitat.[61] Aquests problemes no es limiten als gossos de pedigrí i poden afectar exemplars creuats.[61] Es pot predir en certa mesura el comportament i l'aparença d'un gos d'una raça determinada, mentre que els creuaments presenten un ventall més ample d'aparença i comportament innovadors.

Els gossos mesclats són aquells que no pertanyen a cap raça determinada, sinó que tenen ascendència de diferents races. Tant els gossos de pedigrí com els mesclats són aptes com a companys, animals de companyia, gossos de càrrega o competidors en esports cinòfils. A vegades es creuen gossos de diferents races deliberadament, per a crear races mesclades com ara el Cockapoo, una mescla de cocker spaniel i caniche en miniatura. Aquests creuaments deliberats poden presentar un cert grau de vigor híbrid i altres característiques desitjables, però poden o no poden heretar característiques desitjables dels seus pares, com ara el temperament o un determinat color o pelatge. Si no es fan proves genètiques als pares, els creuaments poden acabar heretant defectes genètics presents en les dues races parents.

Una raça és un grup d'animals que posseeix un conjunt de característiques heretades que els distingeixen d'altres animals de la mateixa espècie. El creuament deliberat de dues o més races també és una manera de crear noves races, però només és una raça quan els descendents presenten de manera fiable aquest conjunt de característiques i qualitats.

En la cultura

Els gossos són percebuts de manera molt diferent segons l'àmbit cultural de què es tracti.

A Europa, els gossos han estat considerat tradicionalment com a companys lleials dels humans, i molt preuats com a gossos de guàrdia, d'atura o de caça. És un dels motius pels quals els gossos s'han establert com uns dels animals de companyia més populars. En el judaisme i el cristianisme (construït sobre el judaisme), el gos no és especialment considerat. Sovint es parla d'ell amb menyspreu o com a exemple de criatura inferior i menyspreable, o com a símbol de pecat (per exemple, Proverbis 26:11: "Com gos que retorna al seu vòmit..."; 2n Samuel 3:8: "Que potser sóc un home de Judà, un cap de gos?"; Mateu 7:6: "No doneu als gossos les coses santes").

En l'islam, les opinions estan molt més diferenciades. Hi ha tres postures doctrinals sobre la puresa del gos:

- El gos és pur

- El gos és impur

- Només la saliva del gos és impura

L'última opció és la que és representada més sovint. Tanmateix, tota regla té una excepció: les preses aportades pels gossos de caça i els llebrers són considerades pures, encara que els gossos les hagin dut amb la boca.

El gos és mencionat en tres ocasions a l'Alcorà:

- Sura 5, Vers 4 - El gos com a exemple d'animal de caça

- Sura 7, Vers 176 - Comparació d'un no creient amb un gos

- Sura 18, Versos 18-22 - Llegenda dels Set Dorments (رقيم = Raqīm, Vers 9, és considerat com a nom del gos per molts comentaristes[62]).

A la Xina, el gos és vist d'una manera bastant pragmàtica. No és ni honrat ni menyspreat, i en algunes províncies del sud del país serveix d'aliment. En la simbologia, representa l'oest, la tardor i a vegades la riquesa. També juga un cert paper en els exorcismes; segons la creença popular, els dimonis mullats amb sang de gos es veuen obligats a revelar la seva forma vertadera.

Història i mitologia

No es coneix amb certesa quina fou la primera cultura en domesticar els gats. Les proves arqueològiques situen la primera domesticació coneguda potencialment a l'any 30000 aC a Bèlgica,[63][64] però amb més certesa al 7000 aC. En canvi, les proves genètiques semblen indicar un origen de l'Àsia oriental pels gossos.[8] En tot cas, sembla evident que els gossos ja havien estat domesticats a l'època de les primeres civilitzacions. La deessa Bau, deïtat de la curació, era venerada a la mitologia sumèria, on se la representava amb un cap de gos. El seu nom és onomatopeic i significa "lladruc".[65] Tot i que la representació més habitual del déu egipci Anubis era amb el cap d'un xacal, en ocasions se'l representava amb el cap d'un gos, i la ciutat que era el centre del seu culte s'anomenava Cinòpolis, o "ciutat dels gossos".

A la mitologia grega hi apareixen diversos gossos llegendaris. Un d'ells és Lèlaps, un gos que de caça que mai no fallava a l'hora d'atrapar la seva presa. Després de passar per mans d'Europa i Minos, el gos arribà a Procris. El marit de Procris decidí utilitzar Lèlaps per a caçar la guineu teumèsia, una guineu que mai no podia ser atrapada. Perplex davant aquesta paradoxa, Zeus convertí el parell d'animals en pedra.

Un altre ca cèlebre de la mitologia grega era Cèrber, un gos de tres caps que custodiava les portes de l'Hades. Aquest ferotge gos només fou vençut dues vegades, una vegada gràcies a la música d'Orfeu (que baixà a l'infern a buscar Eurídice), i l'altra quan l'heroi Hèracles el derrotà sense ajut de cap arma (com a part de les seves dotze tasques). Finalment, a l'Odissea Homer relata l'arribada d'Odisseu a Ítaca, on la deessa Atena li canvia màgicament l'aspecte per tal que no sigui reconegut. Malgrat les arts d'Atena, el gos d'Ulisses, Argos és capaç de reconèixer-lo després de vint anys, però mor de l'emoció.[66]

És un dels dotze animals del cicle de dotze anys del zodíac xinès. Segons el zodíac, les persones nascudes a l'any del gos tenen una especial aversió per la feblesa. S'esforcen per a expulsar la feblesa o les persones febles de la seva vida. Les persones de l'any del gos també solen tenir les qualitats associades amb aquest animal, com la lleialtat o la intel·ligència.

En el folklore de les illes Britàniques hi ha gossos negres, espectres canins sovint associats amb el Diable i que són considerats un presagi de mort. Són més grans que els gossos normals i sovint tenen uns grans ulls lluents.[67] Solen aparèixer durant tempestes elèctriques, i tendeixen a encantar carreteres antigues, creuaments de camins o llocs on s'han executat persones. Tot i que la majoria d'ells són malèvols (i alguns fins i tot ataquen les persones), alguns pocs són benèvols.

Gossos cèlebres de ficció

Els gossos han aparegut en múltiples representacions artístiques tant al cinema com a la televisió, així com a la literatura, la música, l'escultura, la pintura, etc. El seu encant ha travessat les barreres culturals i s'han convertit en un símbol de lleialtat, fidelitat i intel·ligència, però en alguns casos també d'agressivitat.

Al cine i la televisió, apareixen sovint en pel·lícules destinades a un públic infantil com ara Beethoven o 101 Dàlmates, que tingueren un gran èxit. En altres pel·lícules i sèries, es destaquen les seves habilitats com a rastrejadors, presentant-los com a detectius o com a policies. La sèrie austríaca Rex, per exemple, segueix les aventures d'un pastor alemany (Rex) que treballa amb la policia de Viena.

Disney popularitzà els gossos Pluto i Goofy, ambdós com a part de l'univers de Mickey Mouse. També destaquen altres pel·lícules de Disney com The Fox and the Hound, Bolt o La dama i el rodamón, així com Gromit de la producció britànica Wallace i Gromit. Les sèries Dartacan i els tres mosqueters, Scooby Doo també presenten gossos com a personatges principals, i és bastant cèlebre el gos d'Els Simpsons, anomenat Santa's Little Helper. Mentrestant, a la sèrie de televisió britànica Doctor Who hi han aparegut diversos models de K-9, un gos robot capaç de parlar que acompanya el Doctor en diverses aventures.

La dècada del 1950 fou l'auge de dues sèries de televisió protagonitzades per gossos molt cèlebres; Lassie, que seguia les aventures d'un collie en una granja de l'oest mitjà dels Estats Units, i Rin Tin Tin, un gos que, juntament amb el seu company humà, ajudava els soldats a mantenir l'ordre al vell oest. Els còmics també han donat molts gossos de ficció, entre els quals es poden destacar Snoopy, l'excèntric beagle de la tira còmica Peanuts; Odie, el ximplet gos groc que fa la vida impossible al gat Garfield; Milú, el fox terrier que acompanya Tintín en totes les seves aventures, i que té una afecció pel whisky; o Idèfix, un petit gosset amb un lligam molt estret amb el seu amo Obèlix (Astèrix el gal).

En els videojocs, els gossos també són un personatge recorrent. Uns dels que tenen més protagonisme (tot i que el joc passà desaparcebut) són els del joc de PSOne Tail Concerto de Bandai, amb un marcat estil d'anime japonès i on els protagonistes eren animals. Els personatges bons eren els gossos, mentre que els gats eren els dolents, tot i que realment no ho eren tant. Els jocs de la videoconsola Nintendo DS Nintendogs (amb 20.300.000 milions de còpies venudes al setembre del 2008) i Dogz són dos simuladors de gossos que han assolit un gran èxit, i els seus creadors han llançat diversos tipus de productes relacionats, com ara joguines[68] i cartes col·leccionables.[69]

L'èxit del programa de televisió Dog Whisperer (televisat a Espanya amb el nom El encantador de perros), en què César Millán, un ensinistrador de gossos, ajuda la gent a educar i entrenar els seus cans, permeté que fos llançat el videojoc My Dog Coach: Understand your Dog with Cesar Millan, també per la Nintendo DS. El gos Poochie també és un personatge de la saga de videojocs de Yoshi. Als videojocs de Pokémon i la sèrie d'anime homònima apareixen Pokémon semblants a gossos, els més coneguts dels quals són Growlithe i Arcanine; a la sèrie Digimon, alguns tipus de Digimon són gossos, com ara Gaomon.

El padrí de Harry Potter, Sirius Black, juga un paper secundari però important a la saga de llibres, pel·lícules i videojocs de Harry Potter. Harry és seguit per un gos negre a Harry Potter i el pres d'Azkaban, però al final s'acaba revelant que el gos és en realitat Sirius, que és un animag (un mag capaç de transformar-se en animal). Altres exemples d'aparicions de gossos en literatura són la novel·la Ullal blanc de Jack London, el gos espectral d'El gos dels Baskerville d'Arthur Conan Doyle, el gos Argos (que pertany a Odisseu) de l'Odissea d'Homer, el gos Cujo imaginat per Stephen King, o Huan, el gos de Valinor que apareix al Silmaríl·lion (Tolkien).

En l'àmbit musical apareixen múltiples mencions a gossos, com per exemple en l'obra del compositor soviètic Serguei Prokófiev Pere i el llop. També apareixen en moltes cançons com ara Feed Jake de Pirates of the Mississippi, Dog Eat Dog d'AC/DC, Martha My Dear d'Els Beatles, etc.

Referències

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 {{{títol}}}. ISBN 0-226-74338-1.

- ↑ «Humans live a dog's life». abc.net.au, 26-03-2002. [Consulta: 7 abril 2007].

- ↑ «"kwon"». The American Heritage Dictionary, 2000. [Consulta: 2 setembre 2008].

- ↑ Enciclopèdia Catalana. «Entrada "gos" al GDLC». [Consulta: 16 agost 2008].

- ↑ Swaminathan, Nikhil. «Why are different breeds of dogs all considered the same species?». Scientific American.

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 6,2 6,3 6,4 {{{títol}}}. 0684855305.